Paul Revere's Ride (15 page)

Read Paul Revere's Ride Online

Authors: David Hackett Fischer

Tags: #General, #Biography & Autobiography, #History, #United States, #Historical, #Revolutionary Period (1775-1800), #Art, #Painting, #Techniques

These men, who knew so little of America, assured General Gage that the “rebels” of Massachusetts were merely “a rude Rabble without plan, without concert, and without conduct.” Gage was told that “a smaller force now, if put to the test, would be able to encounter them with greater probability of success than might be expected from a greater army.” He was advised that “if the steps taken upon this occasion be accompanied with due precaution, and every means devised to keep the measure secret until the moment of execution, it can hardly fail of success, and will perhaps be accomplished without bloodshed.”

31

It all seemed so easy, three thousand miles away. Still, in the eternal manner of politicians everywhere, the ministers were careful to cover themselves. The Earl of Dartmouth added, “It must be understood, however, after all I have said, that this is a matter for discretion.” In other words, if all went right the Government would claim the credit; if anything went wrong General Gage would bear the blame. Nevertheless, Gage’s orders were clear enough. He was to move quickly and decisively with all the strength at his disposal. In the name of the King himself he was commanded to arrest the leaders of the rebellion, to disarm their followers, and to impose order on the Province of Massachusetts by “law-martial” if necessary.

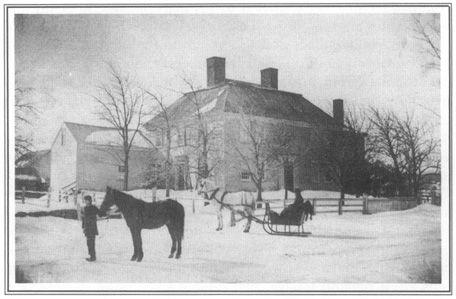

With these instructions on his desk, General Gage studied the calendar. The snow had melted in New England. The ground was still soft, but the season for campaigning would soon begin. It was time to prepare.

British Plans, American Preparations

British Plans, American Preparations

Keep the measure secret until the moment of execution, it can hardly fail of success. … Any efforts of the people, unprepared to encounter with a regular force, cannot be very formidable.

—Earl of Dartmouth to General Gage, Jan. 27, 1775

We may all be soon under the necessity of keeping Shooting Irons.

—Samuel Adams to Stephen Collins, Jan. 31, 1775

IN HIS METHODICAL WAY, General Thomas Gage had already begun to make the necessary preparations, even before his new orders arrived from London. This time he vowed that the outcome would be different—not like the embarrassing fiasco at Portsmouth or the painful humiliation at Salem. The lessons of experience were very clear. He must strike at the heart of the rebel movement and cripple it with quick, clean blows before its large numbers could be mustered against his little army. If he wished to act without awakening the wrath of the continent against him, it was necessary to do these things without the shedding of blood, or at least with as little bloodshed as possible. Everything hinged on secrecy, surprise, and sound intelligence.

On the other side, Whig leaders in New England were preparing too. Forewarned by friends in London, they knew that the British army was about to move against them, but not precisely where or when. They were prepared to fight for their freedom, but they could not start the fight without forfeiting the moral advantage of their cause. These New England Whigs believed that

if shots had to be fired, it was urgently important that a British soldier must be the one to fire first. Only then would America stand united. Samuel Adams was very clear about that. On March 21, 1775, this canny politician reminded his fellow Whigs, “Put your enemy in the wrong, and keep him so, is a wise maxim in politics, as well as in war.”

1

New England leaders resolved not to move until Gage committed his forces. Once he had done so, their intention was to react quickly, and muster their full strength against him with all the force at their command. Everything depended on careful preparation, timely warning, and rapid mobilization.

Each side recognized the critical importance of intelligence, and both went busily about that vital task. But they did so in different ways. The British system was created and controlled from the top down. It centered very much on General Gage himself. The gathering of information commonly began with questions from the commander in chief. The lines of inquiry reached outward like tentacles from his headquarters in Province House. This structure proved a source of strength in some respects, and weakness in others. The considerable resources of the Royal government could be concentrated on a single problem. But when the commander in chief asked all the questions, he was often told the answers that he wished to hear. Worse, the questions that he did not think to ask were never answered at all.

The American system of intelligence was organized in the opposite way, from the bottom up. Self-appointed groups such as Paul Revere’s voluntary association of Boston mechanics gathered information on their own initiative. Other individuals in many towns did the same. These efforts were coordinated through an open, disorderly network of congresses and committees, but no central authority controlled this activity in Massachusetts—not the Provincial Congress or Committee of Safety, not the Boston Committee of Correspondence or any small junto of powerful leaders; not Sam Adams or John Hancock, not even the indefatigable Doctor Warren, and certainly not Paul Revere. The revolutionary movement in New England had many leaders, but no commander. Nobody was truly in charge. This was a source of weakness in some ways. The system was highly inefficient. Its efforts were scattered and diffuse. Individuals demanded a reason for acting, before they acted at all. They wrangled incessantly in congresses, conventions, committees and town meetings. But by those clumsy processes, many autonomous New England minds were enlisted in a

common effort—a source of energy, initiative, and intellectual strength for this popular movement.

In the beginning, General Gage held the initiative. He organized a formal intelligence staff that consisted largely of his kinsmen—mostly relatives by marriage whom he felt that he could trust. His deputy adjutant-general for intelligence was his American brother-in-law, Major Stephen Kemble, an officer in the British army. His confidential secretary was Samuel Kemble, another brother-in-law. His aide-de-camp for confidential matters was his wife’s cousin, Captain Oliver De Lancey.

Young Captain De Lancey was typical of the American Loyalists who joined this new transatlantic Imperial elite. He came from a rich and powerful New York family which owned a large part of Manhattan Island and Westchester County. His uncles included the acting governor of New York and the chief justice of that colony. De Lancey had been sent to school at Eton, and a commission had been bought for him in a crack British cavalry regiment. He joined Gage’s headquarters in 1775.

2

In the winter and spring of 1774—75, two months before Gage’s secret orders arrived, his staff began to collect information about eastern Massachusetts. Every officer in the garrison with knowledge of the countryside was ordered to report to headquarters. Loyalist agents were actively recruited. They began to send a steady flow of information on provincial politics and military affairs.

3

As General Gage studied the reports that came across his desk, his first thought was to revive an earlier plan, and strike at the shire town of Worcester, forty miles west of Boston. That village had become a major center of the revolutionary movement. Various provincial bodies had met there. A large supply of munitions was stored in its houses and barns, and the tools of war were manufactured in its mills. Agents reported that fifteen tons of gunpowder were on hand, and thirteen cannon were parked in front of the Congregational meetinghouse. For many months the inhabitants of Worcester had been outspoken in support of the Whig cause, and had spurned all compromise.

4

As early as the summer of 1774, Gage had written to Dartmouth, “In Worcester they keep no terms, openly threaten resistance by arms, have been purchasing arms, preparing them, casting ball, and providing powder, and threaten to attack any troops who dare to oppose

them.” He concluded: “I apprehend I shall soon be obliged to march a body of troops into that township.”

5

General Gage decided to postpone that plan after the Powder Alarm in September 1774; but through the fall and winter, Worcester continued to be on his mind. In the last week of February 1775, Gage summoned two enterprising young officers, Captain John Brown and Ensign Henry De Berniere of the 10th Foot. He asked them to go out on a confidential mission. They were to dress in plain country clothing and walk from Boston to Worcester, and to return with a sketch of the countryside and a report on the roads. In particular, they were to look for dangerous ambush sites along the way. The need for secrecy was strongly impressed upon them. If anyone asked their business, the British officers were to pretend to be surveyors.

6

De Berniere and Brown were bored by garrison life and leaped at the assignment. The result was yet another bizarre cultural collision between Britain’s Imperial elite and the folkways of New England. The mission began as low comedy, and nearly ended in calamity for the young British officers. They set off on foot, “disguised like countrymen, in brown cloaths and reddish handkerchiefs round our necks.” They were delighted to discover that General Gage himself was unable to recognize them. But when they left town by the Charlestown ferry, a British sentry saluted briskly and nearly gave the game away.

7

They walked west through Cambridge, and by mid-day reached a Whig tavern in Watertown, where they decided to stop for something to eat. The officers had insisted upon traveling with a batman whom they called “our man John.”

8

When they entered the tavern, these young British gentlemen banished their servant to a separate table, and “called for dinner” in what seemed to them an ordinary tone of voice. To their surprise, they noticed that the black serving maid began to “eye us very attentively,” as they wrote in their report.

“It is a fine country,” the officers said in their most agreeable manner, forgetting that they were supposed to be countrymen themselves.

“So it is,” answered the maid with a knowing look, “and we have got brave fellows to defend it, and if you go up any higher you will find it so.”

9

The officers were stunned by her reply. “This disconcerted us a good deal,” they reported, “and we resolved not to sleep there

that night.” They called for the bill, and betrayed themselves again by trying to settle in British sterling an account that had been reckoned in the mysterious complexity of Massachusetts “Old Tenor” currency. While they struggled with the rate of exchange, the black waitress approached their batman again and delivered another gratuitous warning: “She said she knew our errand was to take a plan of the country,” and “advised him to tell us not to go any higher, for if we did we should meet with very bad usage.”

Brown and De Berniere held a quick “council,” and decided that they could not return to Boston without dishonor, an act unthinkable for a British officer. They resolved to push on, but agreed that in deference to the customs of this strange country, their batman would be promoted to a condition of temporary equality with themselves—even at dinner. They wrote in their report, “We always treated him as our companion, since our adventure with the black woman.” At least one human relationship was briefly transformed by the American Revolution, even as it had barely begun.

In wintry weather, the three men continued west on the Old Boston Post Road to the Golden Ball Tavern, which still stands today in the suburban town of Weston. This was a Tory inn. They were treated well, but warned once again not to go higher into the country. Still, they gamely insisted on pressing on. Their Tory host in Weston sent them to a Loyalist tavernkeeper in Marlborough, and from there to another Tory inn in Worcester which they reached on Saturday night. Here again they were treated courteously, and even offered the symbolic dish of tea that proclaimed the politics of the establishment.

The strict New England Sabbath began at sundown on Saturday. The British officers were warned that movement was impossible for them until sunset on Sunday. They explained to their superiors, “We could not think of travelling, as it is contrary to the custom of the country, nor dare we stir out until the evening because of meeting, and nobody is allowed to walk the streets during the divine service, without being taken up and examined.”

When the Sabbath ended on Sunday evening, they left the Tory tavern and mapped the hills and roads around Worcester. Then they started back toward Boston, crisscrossing the country lanes of Middlesex County. They spent their nights in Tory taverns, and took their lunches in the woods, dining on a bit of bread and “a little snow to wash it down.” Even so, their movements were quickly discovered and carefully observed. Groups of silent country

folk gathered in the villages, watching ominously as they walked through. Horsemen rode up to them on the road, studied their appearance without saying a word, then wheeled and galloped away.