Paul Revere's Ride (28 page)

Read Paul Revere's Ride Online

Authors: David Hackett Fischer

Tags: #General, #Biography & Autobiography, #History, #United States, #Historical, #Revolutionary Period (1775-1800), #Art, #Painting, #Techniques

Wherever the alarm arrived after daybreak, the men were already hard at work. In Medfield, they mustered directly from their fields and shops. Captain Ephraim Cheney of that town was ploughing his field. He “unhitched his ox from the plough, left it where it was in the furrow, and started for the scene of the action at once,” Silas Mason did the same. Hatter James Tisdale was “finishing a hat when the news reached him. He dropped the hat and brush, made himself ready, and started.”

23

When officers sometimes moved more slowly than their men, the major decisions were taken out of their hands. This happened in Salem, which did not get the word until eight or nine o’clock in the morning. One of its senior militia officers, Timothy Pickering, was very slow that day, perhaps because he was a conservative Whig and hoped to avoid hostilities. Pickering protested to his men that there was not time enough to march, that the Regulars would be back in Boston before his unit could reach the scene. His men forced him to mobilize and march. Still he delayed on the road, until a private soldier who happened to be one of Salem’s richest merchants told him in no uncertain terms to get moving.

The men of Salem imposed their own judgment on their commander.

24

Congregational ministers actively involved themselves in the muster, helping to awaken the men, leading the consultations, sometimes shouldering a weapon and joining the march themselves. Many companies gathered at their meetinghouses, and did not march until they had united in prayer. The militia from Dedham center heard a prayer from their clergyman as they stood in front of the meetinghouse. Then they all marched off together.

25

In Chelmsford, George Spaulding recalled, “Parson Bridge … wanted us to go into the meetinghouse and have prayers before we left town. Sergeant Ford replied to the good parson, that he had more urgent business on hand.” But some sort of prayer was a common part of mobilization in New England.

26

If the meetinghouses were part of the muster, so also were the families of New England. Some of the small towns in Middlesex County were 145 years old in 1775. For as many as six generations their families had interbred until they were extended cousinages, closely tied by blood and marriage. In Bedford’s company, for example, it was said that “all 77 men with few exceptions were related.” In Captain John Parker’s Lexington’s militia company, “over a quarter of those responding were his blood relatives or in laws.”

27

Older men joined their sons and grandsons as volunteers. In Lexington, Moses Harrington was sixty-five years old. Robert Munroe was sixty-three. Sudbury’s Deacon Josiah Haynes was eighty years old, but turned out with the militia and set a rapid pace on the road that left the young minutemen panting behind him. The militia were joined by large numbers of these “un-enlisted volunteers” as they were called in Littleton. In Dedham, after the militia marched, “The gray-haired veterans of the French wars, whose blood was stirred anew by the sights and sound of war, resolved to follow their sons into battle.” Many of these older men had much military experience. They would be among the most dangerous adversaries on the field that day.

28

In many communities virtually the entire male population marched off to war. Dedham’s minister remembered that the village was “almost literally without a male inhabitant below the age of seventy, and above that of sixteen.”

29

Woburn’s Major Loammi Baldwin wrote in his diary, “We mustered as fast as possible. The town turned out extraordinary, and proceeded toward Lexington.”

30

They dressed in ordinary working clothes. The men were clean-shaven, with long hair worn straight or pulled back in a queue, beneath large weatherbeaten hats with low round crowns and broad floppy brims. Among the younger men, earlocks were much in fashion, fastened with elegant pins on the side of the head. One eyewitness observed that “to a man they wore smallclothes, coming down and fastening just below the knee, and long stockings with cowhide shoes ornamented by large buckles.”

31

Their shirts were linen and their stockings were heavy gray homespun. As the night air was chill, many were wearing both coats and vests. An observer remarked that their “coats and waistcoats were loose and of huge dimensions, with colors as various as the barks of oak, sumac and other trees of our hills and swamps could make them.” These were old New England’s traditional “sadd colors.”

32

A few gentlemen of rank turned out in gaudy costumes. Brookline’s Doctor William Aspinwall arrived at his town muster wearing an elegant and fashionable broadcloth coat of brilliant scarlet. His neighbors tactfully suggested that a coat of another color might be more suitable for the occasion. Dr Aspinwall hurried home and changed into an outfit that would not be mistaken for British regimentals.

33

The firearms of these men were as various as their dress. The towns for many years had been required to keep their own supply of munitions. Some had maintained magazines in the Congregational meetinghouses. At Lexington barrels of gunpowder were stored as a “common stock” below the pulpit—a symbolic place in the minds of many Loyalists who had long complained against the explosive theology of the “black regiment” of the Congregational clergy. Littleton’s company of 46 men marched off with 24 pounds of powder, and 38 pounds of bullets drawn from the “common stock.”

34

Most towns expected individual militiamen to supply their own weapons, and acted only to arm those who were unable to arm themselves. Newton’s town meeting made special provision to arm its paupers at public expense: “Voted, that the Selectmen use their best discretion in providing fire-arms for the poor of the Town, who are unable to provide for themselves.” Not many societies in the 18th century would have dared to distribute weapons to their proletariat. At the same time, the rich applied the New England habit of philanthropy to an unaccustomed cause. The town meeting in Newton also noted that “John Pigeon presented to the town two field pieces, which were accepted, and the thanks of the town given him.”

35

New England Fowler, Museum of Our National Heritage, Lexington John Parker’s Musket, Massachusetts State House British Musket, Museum of Our National Heritage British Officer’s Fusil, Concord Museum

These were the most common types of firearms at Lexington and Concord. The long-barreled export fowler (top) was a hunting gun, carried on April 19 by Ezekiel Rice (1742-1835) of East Sudbury (now Wayland). It is owned by Peter A. Albee and exhibited at the Museum of Our National Heritage. The New England musket (2d from top) was carried by Captain John Parker on Lexington Green. It has no maker’s marks, but appears to be of British or French manufacture with American replacement parts, and bears signs of heavy use, including extensive burn back from the pan. It is kept today in the Massachusetts Senate Chamber. The British Brown Bess was a long land pattern musket carried by many British units in Concord. This one is in the Museum of Our National Heritage. The short-barreled British Fusil was used by officers and sergeants in Grenadier companies. This example bears the markings of the 5th Foot and might have been carried by Lt. Thomas Baker, Sgt. George Kirk, or Sgt. Thomas Allen of the 5th Grenadiers, all of whom were wounded in the battle. Captured by an American militiaman, it is in the Concord Museum.

Town stocks of munitions had been been growing in the winter and spring of 1775, despite the British embargo. But many militia and minute companies were still short of gunpowder and weapons on April 18. A few were not armed at all. Lincoln’s Colonel Abijah Pierce carried nothing but a cane. His town had voted to furnish supplies a month earlier, but it was reported that only a “few were as yet well equipped.”

36

Many men armed themselves with weapons not designed for war. One man from Lynn carried a “long fowling piece, without a bayonet, a horn of powder, and a seal-skin pouch, filled with bullets and buckshot.

37

Some carried arms of great antiquity, whose origins told the history of the province. A witness wrote, “Here an old soldier carried a heavy Queen’s arm with which he had done service at the conquest of Canada twenty years previous, while by his side walked a stripling boy with a Spanish fusee not half its weight or calibre, which his grandfather may have taken at the Havana, while not a few had old French pieces, that dated back to the reduction of Louisburg.” None of these Massachusetts militia are known to have carried long rifles such as were becoming popular in Pennsylvania and the southern backcountry. Despite the urgings of the Congress, few had cartridge boxes or bayonets. Their few precious lead bullets were carefully wrapped in handkerchiefs and carried in pockets or under their hats. Gunpowder was carried in horns that had been passed down from father to son for many generations. Inscriptions carved onto these powder

horns told their history. Lexington’s historical society cherishes a powder horn that descended from generation to generation in the Harrington family of that town. One of its owners carved his name into its side: “Jonathan Harrington His Horne, May the 4 AD 1747.” It was later owned by the boy fifer Jonathan Harrington, the youngest soldier who mustered on Lexington Green on April 18, 1775. New England powder horns were elaborately decorated by professional carvers, in a manner much like scrimshaw. One ambivalent horn by Jacob Gay displayed the Royal arms of Britain on one side, and Paul Revere’s print of the Boston Massacre on the other. Another made in Roxbury depicted “Tom Gage” as a diabolical figure, with a forked tail, sharp horns, and a serpent in his hand. Some showed idyllic scenes of town commons, and New England churches. Many were adorned with folk motifs, patriotic slogans, personal inscriptions, and snatches of homespun poetry that expressed the values of this culture. It is interesting to compare these objects with the artifacts of other American wars. The inspiring scenes and slogans carved into the powder horns of the American Revolution were profoundly different from the sentiments of alienation, anomie, self-pity, and profound despair inscribed on helmet covers and field equipment in Vietnam. In 1775, even young militia privates who were still in their teens, clearly understood what they were doing, and deeply believed in the cause that they were asked to defend.

38

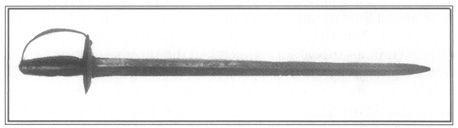

Among the variety of edged weapons carried by militia, one type often appeared in New England. It was a short rapier with a flattened diamond blade that had been made in Europe during the 17th century. At a later date, a New England blacksmith gave it a simple American grip. Many of these austere but efficient weapons have been found in Middlesex and Essex counties, where they had been in use since the mid-17th century—another material indicator of continuity in New England’s culture. (Museum of Our National Heritage, Lexington)

Officers and some private soldiers carried swords that were also material expressions of New England’s culture and history. Their edged weapons were as various as firearms, but one distinctive type often appeared in eastern Massachusetts. It was short rapier with an antique steel blade that had been imported from continental Europe, and reset with a plain but functional grip by a Yankee blacksmith. This weapon was austere and very old-fashioned in its appearance, much like the short swords of Cromwell’s New Model Army. In America the Middlesex sword was another cultural artifact, like the powder horns and firelocks and dress, that revealed the origins of the New England way, and the continuity that extended from the founding of the Puritan Colonies to the revolutionary movement of 1775.

39

Some units carried flags of great antiquity, which had been passed down from the Puritan founders of New England. One of them survives today in the town of Bedford, Massachusetts. It was made in England sometime in the 17th century, and used as early as 1659 in Massachusetts. Against a crimson background, it shows the arm of God reaching down from the clouds, with a short sword in a mailed fist. A Latin motto reads, “Vince aut Morire” (Conquer or Die). According to the traditions of the town, this flag was carried on the morning of April 19, 1775, by Cornet Nathaniel Page of the Bedford militia.

40