Paul Revere's Ride (29 page)

Read Paul Revere's Ride Online

Authors: David Hackett Fischer

Tags: #General, #Biography & Autobiography, #History, #United States, #Historical, #Revolutionary Period (1775-1800), #Art, #Painting, #Techniques

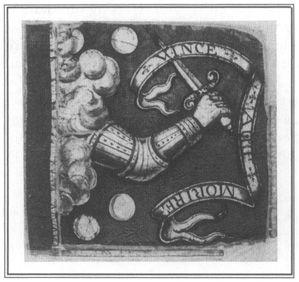

The Bedford Flag is thought to be the oldest surviving banner in English-speaking America. (Bedford Public Library)

Like their Puritan ancestors whose banner they carried, these citizen-soldiers of Massachusetts were very clear about their purposes. They called to mind Oliver Cromwell’s plain russet-coated captain, who knew what he fought for, and loved what he knew.

Many years later Captain Levi Preston of Danvers was asked why he went to war that day. At the age of ninety-one, his memory of the Lexington alarm was crystal clear, and his understanding was very different from academic interpretations of this event. An historian asked him, “Captain Preston, what made you go to the Concord Fight?”

“What did I go for?” the old man replied, subtly rephrasing the historian’s question to drain away its determinism.

The interviewer tried again. “… Were you oppressed by the Stamp Act?” he asked.

“I never saw any stamps,” Preston answered, “and I always understood that none were ever sold.”

“Well, what about the tea tax?”

“Tea tax, I never drank a drop of the stuff, the boys threw it all overboard.”

“But I suppose you have been reading Harrington, Sidney, and Locke about the eternal principle of liberty?”

“I never heard of these men. The only books we had were the Bible, the Catechism, Watts’ psalms and hymns and the almanacs.”

“Well, then, what was the matter?”

“Young man, what we meant in going for those Redcoats was this: we always had governed ourselves and we always meant to. They didn’t mean we should.”

41

A Rural Panic in New England

A Rural Panic in New England

Nor will old Time ever erase the horrors of the midnight cry preceding the Bloody Massacre at Lexington.

—Hannah Winthrop

A

FTER THE MILITIA

marched away, early in the morning of April 19, the mood was dark in the towns they left be-

JL

JL

hind. Nearly everyone believed that this was no mere drill or demonstration. On both sides, there was a strange and fatal feeling that bloodshed was inevitable.

The people of New England did not wish for war. This was not a warrior culture. It did not seek glory on the field of valor, and showed none of the martial spirit that has appeared in so many other times and places. There were no cheers or celebrations when the militia departed—nothing like the wild exultation of the American South at the outbreak of the Civil War, or the bizarre blood-lust of the European middle classes in 1914.

The people of New England knew better than that. In 140 years they had gone to war at least once in every generation, and some of those conflicts had been cruel and bloody. Many of the men who mustered that morning were themselves veterans of savage fights against the French and Indians. They and their families knew what war could do. The mood in Massachusetts was heavy with foreboding.

In the town of Acton, Hannah Davis always remembered the terrible moment when her husband left her. He was about thirty years old, and the captain of Acton’s minute company. She was

twenty-nine. Their children were very young, one of them a babe in arms. The season had been sickly in the Davis household. That morning all the children were ill, some with the dreaded symptoms of canker rash, a mortal disease that ravaged many a New England household. The Davis household had been awakened before dawn by an alarm rider. While Hannah comforted her crying children, the minutemen of Acton trooped into her kitchen, filling that small feminine space with the strong masculine presence of their muskets, bayonets, tomahawks, and powder horns.

Hannah remembered later that “my husband said but little that morning. He seemed serious and thoughtful; but never seemed to hesitate as to the course of his duty.” As he left the house, Isaac Davis suddenly turned and faced his wife. She thought he wanted to tell her something, and her heart leaped in her breast. For a moment he stood silent, searching for words that never came. Then he said simply, “Take good care of the children,” and disappeared into the darkness. Hannah was overwhelmed by an agony of emptiness and despair. By some mysterious power of intuition, she knew that she would never see him again.

1

Other women shared that feeling as they watched their husbands march away. After the men were gone these individual emotions flowed into one another like little streams into a river of fear that flooded the rural towns of Massachusetts. On a smaller scale, it was not unlike the

grande peur

that swept across the French countryside in 1789, when ordinary people were suddenly consumed with a sense of desperate danger.

2

The great fear in New England began with the first alarm that was spread by Paul Revere and the other midnight riders. We remember that moment as a harbinger of Independence. For us, it was an event bright with the promise of national destiny. But at the time it was perceived in a very different way—as a fatal calamity, full of danger, terror, and uncertainty. Many years afterward, Hannah Winthrop recorded her feelings of the moment, which were still very strong in her mind. “Nor will old Time ever erase,” she wrote, “the horrors of the midnight cry preceding the Bloody Massacre at Lexington.”

3

Hannah Winthrop lived in Cambridge, where her husband John taught natural science at Harvard College. He was an elderly man, and not in good health. They lived near the Lexington Road, and felt themselves in harm’s way. In company with many others, Hannah Winthrop’s first impulse was to flee. She later wrote, “Not

knowing what the event would be at Cambridge … it seemed necessary to retire to some place of safety till the calamity was passed. My partner had been a fortnight confined by illness. After dinner we set out not knowing whither we went, we were directed to a place called Fresh Pond about a mile from the town.”

On the road they met a throng of fugitives who also sought safety in flight. When they reached Fresh Pond, the Winthrops stopped at a home by the road, and found it full of terrified refugees. “What a distressed house did we find there,” Hannah wrote, “filled with women whose husbands were gone forth to meet the assailants, 70 or 80 of these, with numbers of infant children, crying and agonizing over the fate of their husbands.”

The great fear had already taken possession of that teeming crowd. Hannah Winthrop and her invalid husband decided to flee again, this time to northern Massachusetts. “Thus,” she wrote, “with some precipitancy were we driven to the town of Andover, following some of our acquaintances, five of us to be conveyed by one tired horse and chaise.” The burden was too heavy for the horse, and the five refugees had to take turns in the chaise. “We began our passage alternately walking and riding,” Hannah Winthrop later recalled, “the roads [were] filled with frightened women and children, some in carts with their tattered furniture, others on foot fleeing into the woods.”

4

The narrow country roads were jammed with traffic. Militiamen were advancing toward Lexington and Concord—some as individuals, others in small parties, many in entire companies marching behind a fife and drum. At the same time, women and children and noncombatant men were fleeing in the opposite direction. Carts and coaches were piled high with cherished possessions. Along the shoulders of the roads were forlorn groups of fugitives, the broken shards of shattered families who were traveling sadly they knew not where—anywhere that took them farther from the great fear that followed them.

While some people took to the roads, others hid themselves in the woods. In Lexington many families of the militia left their homes and disappeared into patches of forest. It was later remembered of Rebecca Harrington Munroe, whose male relatives made up a large part of Captain Parker’s company, that this “worthy lady,” with “other families in Lexington, fled on the 19th of April 1775, with their children to the woods, while their husbands were engaged with the enemy and their houses were sacked or involved in flames.”

5

Others ran to their neighbors and sought safety in the midst of others, sometimes in places very bizarre. In Charlestown on April 19, Jacob Rogers remembered, “I… put my children in a cart with others then driving out of town. … We proceeded with many others to the town’s Pest House.” This was a remote building where smallpox victims were confined. Others in Charlestown went to a building near the training field, “full of women and children in the greatest terror, afraid to go to their own habitations.”

6

Many hoped to find a place of sanctuary in the churches of New England. Lexington’s meetinghouse was a large but fragile wooden building, sheathed in clapboards that could scarcely have stopped a pistol ball. It stood directly in the path of the approaching British Regulars, and very much in harm’s way. Even so, the people found spiritual strength in their place of worship.

7

Some of the clergy did what they could to help their frightened congregations. A craven few fled for their lives. In Weston after the militia left town, clergymen Samuel Cooper and Samuel Woodward became refugees themselves, fleeing first to Framingham ten miles west and then to Southborough, taking with them a cow and a skillet and a few provisions.

8

In Menotomy, Deacon Joseph Adams fled from his own house to the home of the minister Samuel Cooke, and buried himself in the hayloft of the minister’s barn.

9

But most ministers stayed and tried to comfort members of their congregations who came for help. At Concord, on the morning of April 19, many terrified people hurried to the house of their minister, the Reverend William Emerson. Even as the fighting went on only a few yards away, an eyewitness remembered that “the lane in front of the house was nearly filled with people who came to the minister’s house for protection,” While soldiers marched and countermarched, William Emerson worked outside in the yard, moving among the women and children, and giving them bread and cheese and comfort.

10

The minister’s wife, Phebe Bliss Emerson, was deeply frightened. According to family tradition, Phebe was “delicate,” a euphemism that commonly referred to a mental state rather than a physical condition. She had heard the alarm from her African slave Frank, who came running into her chamber with an axe in his hand, shouting that the Redcoats were coming. Phebe Emerson turned as white as a Concord coverlet and fainted away on the spot. When she revived, she looked around for her husband and saw him outside in the yard, helping people of the town who had

gathered in front of the Old Manse. Phebe Emerson rapped sharply on the windowpane to get her husband’s attention, and told him that “she thought she needed him as much as the others.”

11

Many people managed their fear by keeping very busy. In Watertown, tax collector Joseph Coolidge went off as a volunteer to show a militia company the road to Lexington. His wife busied herself by digging a hole, and burying the town’s tax books for safekeeping.

12

Alice Stearns Abbott, then a child of eleven, later remembered that she and her sisters Rachel and Susanna awakened early. “We all heard the alarm,” she recalled, “and were up and ready to help fit out father and brother, who made an early start for Concord. We were set to work making cartridges and assisting mother in cooking for the army. We sent off a large quantity of food for the soldiers, who had left home so early that they had but little breakfast. We were frightened by hearing the noise of the guns.”

13

Drinking men, of whom there were many in the rural towns of Massachusetts, dealt with their fears in a different way. In Menotomy two brothers-in-law named Jason Winship and Jabez Wyman took refuge in the Cooper Tavern. While confusion reigned around them, they ordered large mugs of flip, a potent drink much favored by tavern topers in the 18th century. They were sitting directly in the path of the British soldiers. Others warned them to flee for their lives. But as the alcohol warmed their spirits, they began to forget their fear. Jabez said to Jason, “Let us finish the mug, they won’t come yet.”

14