Paul Revere's Ride (33 page)

Read Paul Revere's Ride Online

Authors: David Hackett Fischer

Tags: #General, #Biography & Autobiography, #History, #United States, #Historical, #Revolutionary Period (1775-1800), #Art, #Painting, #Techniques

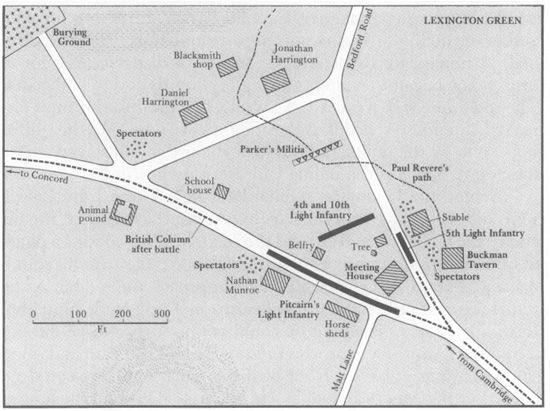

As the Regulars came closer they saw Captain Parker’s militia near the northeast corner of the Common, hurrying into line to the long roll of William Diamond’s drum. The Lexington men were forming up in two long ranks, partly hidden by the meetinghouse. To the left and right of the Common the British soldiers observed two other groups, mostly male, some of them armed.

Perhaps an observant Regular at the head of the column might have noticed two figures staggering across the Common with a heavy burden between them. One of these men was Paul Revere. With his gift for being at the center of events, he happened to be crossing Lexington Common just at the moment when the British troops arrived. Revere and John Lowell had emerged from the Buckman Tavern with John Hancock’s trunk just as the Lexington militia were falling into formation. Their route took them directly through the long ranks of the soldiers. Paul Revere heard Captain John Parker speak to his company. “Let the troops pass by,” Parker told his men. He added in the archaic dialect of old New England, “Don’t molest them, without they being first.”

16

At the same moment the British officers were studying the militia on the Common in front of them. Paul Revere’s warning of 500 men in arms echoed in their ears. As the officers peered through the dim gray light, the spectators to the right and left appeared to be militia too. Captain Parker’s small handful of men multiplied in British eyes to hundreds of provincial soldiers.

17

Pitcairn thought that he faced “near 200 of the rebels;” Barker reckoned the number at “between two and three hundred.”

18

On the other side, the New England men also inflated the size of the Regular force, which was magnified by the length of its marching formation on the narrow road. As the militia studied the long files of red-coated soldiers, some reckoned the force at between

1200 and 1500 men. In fact there were only about 238 of all ranks in Pitcairn’s six companies, plus the mounted men of Mitchell’s patrol, and a few supernumeraries.

19

The Lexington militia began to consult earnestly among themselves. Sylvanus Wood, a Woburn man who joined them, had made a quick count a few minutes earlier and found to his surprise that there were only thirty-eight militia in all. Others were falling into line, but altogether no more than sixty or seventy militia mustered on the Common, perhaps less. One turned to his captain and said, “There are so few of us it is folly to stand here.”

20

But Parker had decided that the time for debate had ended. He turned to his men and told them, “The first man who offers to run shall be shot down.” Some heard him say, “Stand your ground! Don’t fire unless fired upon! But if they want to have a war let it begin here!”

21

The Regulars came closer. To men on both sides, time itself seemed to stop—a temporal illusion that often occurs in moments of mortal danger. When the mind begins to move at lightning speed, the world itself seems to slow down. But in fact events were unfolding at a rapid rate. The Regulars came hurrying on at the quick march. Swarming around the head of the column was a cloud of mounted British officers—the same men who had captured Paul Revere and been told that they were in mortal danger. Many were highly excited. Prominent among them was the mercurial Major Mitchell.

In the British van was Marine lieutenant Jesse Adair, the hard-charging young Irishman who had been put at the head of the column by Major Pitcairn to keep it moving. Adair was a bold and aggressive officer—quick to act, but sometimes slow to understand.

22

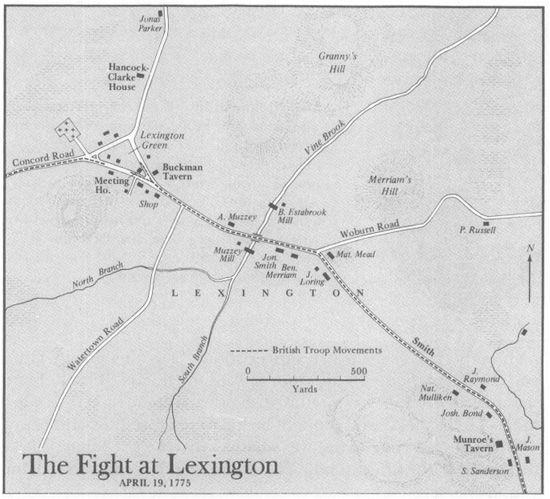

As he approached Lexington Common this young Marine had a momentous decision to make. The main road divided just before it reached the meetinghouse. Adair’s Loyalist guide would have told him that the left fork led to Concord, running along the southwest edge of the Green. The right fork carried toward the northeast, past the Buckman Tavern to the Bedford Road.

Lieutenant Adair found himself in a dilemma. To bear left on the main road toward Concord would leave an armed and possibly hostile force on the open flank of his column. To take the right fork would carry the Regulars headlong toward the militia. The choice was his to make. His immediate superior, Major Pitcairn, was back in the column and could not help him. The commander

of the expedition, Colonel Smith, was far in the rear with the grenadiers, and completely out of touch.

The young Marine did not hesitate. He made a snap decision of momentous consequence. Lieutenant Adair instantly turned to the right, and led the three forward companies directly toward the militia. “No sooner did they come in sight of our company,” Lexington’s minister later wrote, “but one of them, supposed to be an officer of rank, was heard to say to the troops, ‘Damn them, we will have them!’”

23

Back in the column Major Pitcairn saw what had happened, and kicked his horse into a canter, riding rapidly to the front. As he reached the fork, Pitcairn decided differently from Adair. He turned left instead of right, and the rest of the column followed him. It separated from the van and marched along the left fork that ran southwest of the meetinghouse. Beyond that building, Pitcairn halted them in the Concord Road. Somebody also stopped the last of Adair’s three forward companies just beyond the meetinghouse, near the spreading oak tree.

24

Two companies, light infantry of the 4th and 10th Foot, continued straight toward the Lexington militia. In this critical moment Pitcairn lost touch with those men. Adair led them onward at an accelerating pace. The quick march became a run that took the Regulars halfway across the Common in a few moments. About seventy yards from the militia, the two leading companies were ordered to deploy from a column into a line of battle. The men in the rear came sprinting forward. Sergeants and subalterns dropped back to take their places behind the line. The long files dissolved in a swirl of movement. The Regulars began to shout the deep-throated battle cry that was distinctive to British infantry—a loud “huzza! huzza! huzza!” Orders were difficult to hear above the cheering. One British officer remembered that he was deafened by the shouts of his own men.

25

Pitcairn cantered across the Common toward the British line. Other mounted officers were already there. A Lexington militiaman, Elijah Sanderson, observed that “several mounted British officers were forward, I think five. The commander rode up, with his pistol in his hand, on a canter, the others following, to about five or six rods from the company, and ordered them to disperse. The words he used were harsh. I cannot remember them exactly.”

26

Many believed that this officer was Major Pitcairn, but others were unsure of his identity and uncertain of his words. Several men on both sides heard an officer shout, “Lay down your arms, you damned rebels!” In the front rank of the militia, John Robbins saw a party of three mounted British officers come directly toward him at “full gallop,” and thought he heard the foremost officer say, “Throw down your arms, ye villains, ye rebels.” Jonas Clarke thought that the officer said, “Ye villains, ye rebels, disperse, damn you, disperse!”

27

Major John Pitcairn (Royal Marines) was British commander in the skirmish on Lexington Green. Born in 1722, he was an officer of long experience, very near the end of his career. A strong Scottish Tory, he had no sympathy for the colonists; but American Whigs admired his character if not his principles. A New England clergyman described him as “a good man in a bad cause.” (New England Historic and Genealogical Society)

Lexington’s commander, Captain Parker, turned to his men and gave them new orders, different from before. He later testified, “I immediately ordered our militia to disperse and not to fire.” Some began to scatter, moving backwards and to both sides. The town minister Jonas Clarke wrote, “Upon this, our men dispersed, but not so speedily as they might have done.” In the confusion, some of the militia did not hear the order and stayed where they were. None of the militia laid down their arms.

28

Behind the Lexington militia, Paul Revere and John Lowell were still struggling with their trunk. At last they reached the far end of the Common and crossed the road, heading toward a patch of woods beyond a house. Paul Revere glanced back over his shoulder and saw the red-coated Regulars approach the militia. As he returned to his task, suddenly he heard a shot ring out behind him. It sounded like a pistol, but he could not be sure, and he did not see where it came from or who fired it. He looked again and saw a cloud of white smoke in front of the Regulars. Revere could no longer see the American militia. He had passed beyond the houses on the edge of the Green, and a building blocked his sight. Later, his testimony indicated that he could not tell who fired first. With John Lowell he went back to his work, carrying the trunk to a place of safety.

29

On the other side, Lieutenant Edward Gould was very near the center of the action. As an officer of light infantry in the King’s Own, he was part of the force that Adair led directly toward the militia. As the two lines drew near, Gould heard the sharp report of a gun. Like Paul Revere he could not see where it came from, and was unable even to hear it clearly because his own men were cheering wildly. Lieutenant Gould, like Revere, was an honest man and a careful observer. He later testified, “Which party fired first I cannot exactly say, as our troops rushed on shouting and huzzaing.”

30

As the bitter smell of black powder began to spread across the Common, men on both sides searched quickly around them, looking for the source of the shot. On that field of confusion, one fact was clear enough. Nearly everyone, British and American, agreed that the first shot did not come from the ranks of Captain Parker’s militia, or from the rank and file of the British infantry.

31

Several British officers were convinced that they saw a “provincial” fire at them from behind a “hedge” or stone wall, some distance away from Parker’s line. Lieutenant Sutherland of the 38th Foot wrote, “Some of the villains were got over the hedge, fired at us, and it was then and not before that the soldiers fired.” Major Pitcairn to his dying day believed that “some of the Rebels who had jumped over the wall, fired 4 or 5 shott at the soldiers… upon this, without any order or regularity, the Light Infantry began a scattered fire.”

32

It might have been so, but other Regulars thought that the first shot came from “the corner of a large house to the right of the Church,” which could only have been the Buckman Tavern. This also could have happened. Many armed men had been in the Buckman Tavern that night, and more than a few had partaken liberally of the landlord’s hospitality. Firearms and alcohol made a highly explosive mixture.

33

The Lexington men saw things differently. Most believed that the first shots were “a few guns which we took to be pistols, from some of the Regulars who were mounted on horses.” As many as five or six mounted men were present with the forward companies. Most of the Lexington militia, only thirty yards from these men, clearly saw one of these British officers fire at them.

34