Paul Revere's Ride (52 page)

Read Paul Revere's Ride Online

Authors: David Hackett Fischer

Tags: #General, #Biography & Autobiography, #History, #United States, #Historical, #Revolutionary Period (1775-1800), #Art, #Painting, #Techniques

Forbes mistakenly asserts (and Weisberger and others repeat after her) that Revere made his first ride on Nov. 30, 1773. “It was decided that neighboring seaports should be warned that the tea ships might try to unload at their wharves. Paul Revere and five other men were chosen to ride express (Forbes,

Revere,

190). In this she is inaccurate. A meeting at Old South voted that six persons “who are used to horses be in readiness to give an alarm in the country towns, where necessary.” They were William Rogers, Jeremiah Belknap, Stephen Hall, Nathaniel Cobbett and Thomas Gooding of Boston, and Benjamin Wood of Charlestown. See Drake,

Tea Leaves,

xlv.

Forbes also has Revere riding back to Boston after the battle of April 19, 1775. This too is unsupported by evidence.

APPENDIX D

Paul Revere’s Role in the Revolutionary Movement

Paul Revere’s Role in the Revolutionary Movement

The structure of Boston’s revolutionary movement, and Paul Revere’s place within it, were very different from recent secondary accounts. Many historians have suggested that this movement was a tightly organized, hierarchical organization, controlled by Samuel Adams and a few other dominant figures. These same interpretations commonly represent Revere as a minor figure who served his social superiors mainly as a messenger.

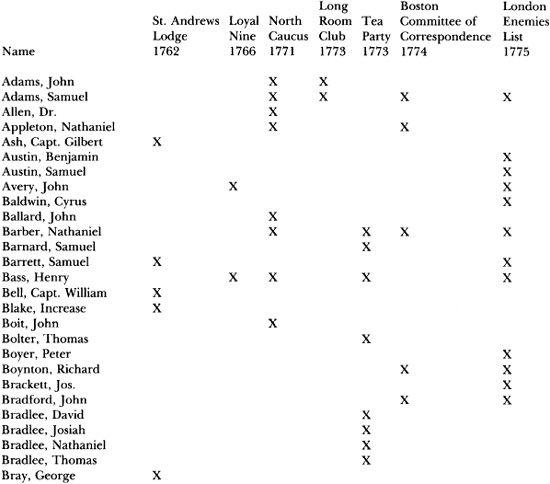

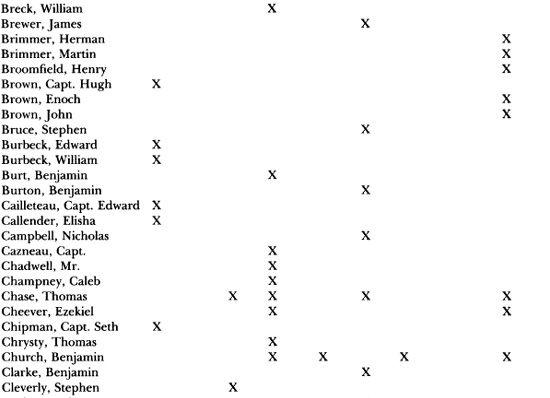

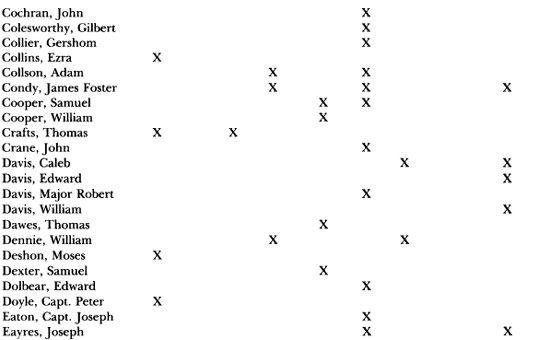

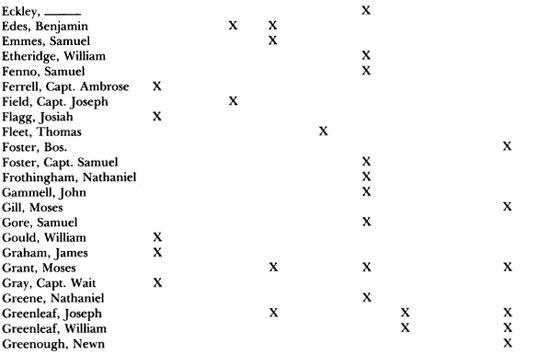

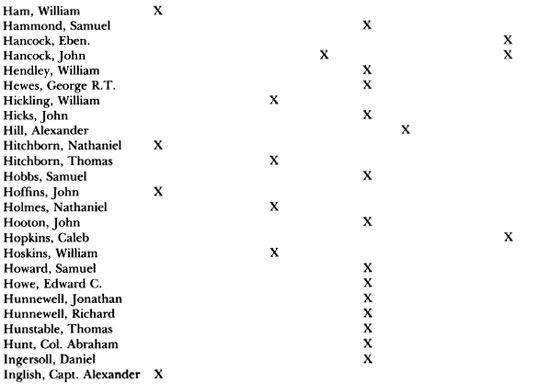

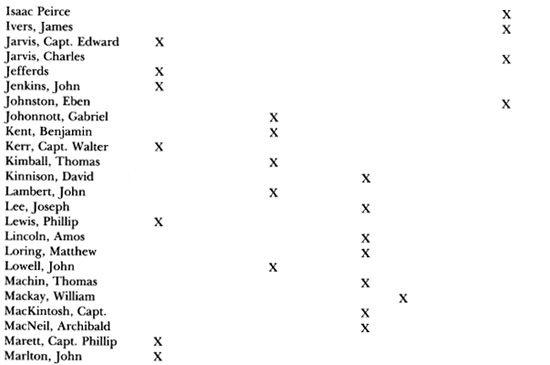

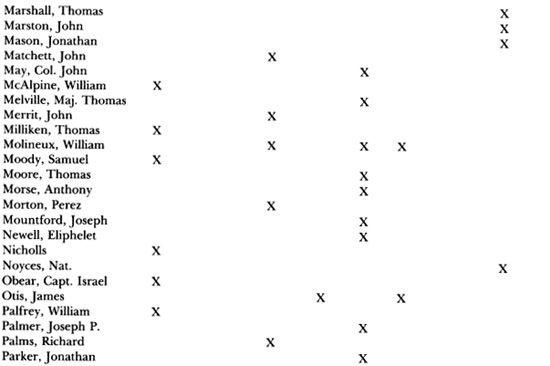

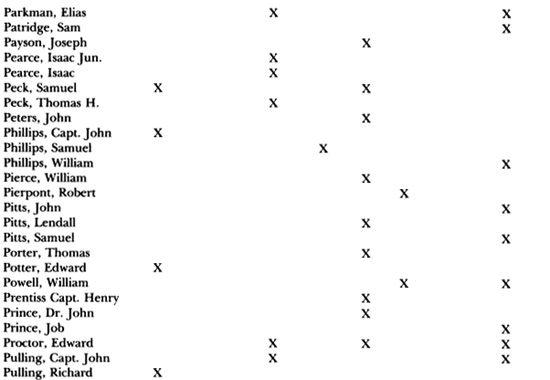

A very different pattern emerges from the following comparison of seven groups: the Masonic lodge that met at the Green Dragon Tavern; the Loyal Nine, which was the nucleus of the Sons of Liberty; the North Caucus that met at the Salutation Tavern; the Long Room Club in Dassett Alley; the Boston Commitee of Correspondence; the men who are known to have participated in the Boston Tea Party; and Whig leaders on a Tory Enemies List.

A total of 255 men were in one or more of these seven groups. Nobody appeared on all seven lists, or even as many as six. Two men, and only two, were in five groups; they were Joseph Warren and Paul Revere, who were unique in the breadth of their associations.

Other multiple memberships were as follows. Five men (2.0%) appeared in four groups each: Samuel Adams, Nathaniel Barber, Henry Bass, Thomas Chase, and Benjamin Church. Seven men (2.7%) turned up on three lists (James Condy, Moses Grant, Joseph Greenleaf, William Molineux, Edward Proctor, Thomas Urann, and Thomas Young). Twenty-seven individuals (10.6%) were on two lists (John Adams, Nathaniel Appleton, John Avery, Samuel Barrett, Richard Boynton, John Bradford, Ezekiel Cheever, Adam Collson, Samuel Cooper, Thomas Crafts, Caleb Davis, William Dennie, Joseph Eayrs, William Greenleaf, John Hancock, James Otis, Elias Parkman, Samuel Peck, William Powell, John Pulling, Josiah Quincy, Abiel Ruddock, Elisha Story, James Swan, Henry Welles, Oliver Wendell, and John Winthrop). The great majority, 211 of 255 (82.7%), appeared only on a single list. Altogether, 94.1% were in only one or two groups.

This evidence strongly indicates that the revolutionary movement in Boston was more open and pluralist than scholars have believed. It was not a unitary organization, but a loose alliance of many overlapping groups. That structure gave Paul Revere and Joseph Warren a special importance, which came from the multiplicity and range of their alliances.

None of this is meant to deny the preeminence of other men in different roles. Samuel Adams was specially important in managing the Town Meeting, and the machinery of local government, and was much in the public eye. Otis was among its most impassioned orators. John Adams was the penman of the Revolution. John Hancock was its “milch cow,” as a Tory described him. But Revere and Warren moved in more circles than any others. This

gave them their special roles as the linchpins of the revolutionary movement—its communicators, coordinators, and organizers of collective effort in the cause of freedom.

The following table does not include all the many associations in Boston that were part of the revolutionary movement. Another list (too long to be included here) survives of 355 Sons of Liberty who met at the Liberty Tree in Dorchester in 1769. Once again, Paul Revere appears on it. There were at least two other Masonic lodges in Boston at various periods before and during the Revolution; Paul Revere is known to have belonged to at least one of them. In addition to the North Caucus, there was also a South Caucus and a Middle Caucus. Paul Revere may or may not have belonged to them as well; some men joined more than one. No definitive lists of members have been found. But it is known that Revere was a member of a committee of five appointed “to wait on the South End caucus and the Caucus in the middle part of town,” and that he met with them (Goss,

Revere,

II, 639). Several Boston taverns were also centers of Whig activity. Revere had connections with at least two of them—Cromwell’s Head, and the Bunch of Grapes. The printing office of Benjamin Edes was another favorite rendezvous. In the most graphic description of a gathering there by John Adams, once again Paul Revere was recorded as being present.

In sum, the more we learn about the range and variety of political associations in Boston, the more open, complex and pluralist the revolutionary movement appears, and the more important (and significant) Paul Revere’s role becomes. He was not

the

dominant or controlling figure. Nobody was in that position. The openness and diversity of the movement were the source of his importance.