Paul Revere's Ride (55 page)

Read Paul Revere's Ride Online

Authors: David Hackett Fischer

Tags: #General, #Biography & Autobiography, #History, #United States, #Historical, #Revolutionary Period (1775-1800), #Art, #Painting, #Techniques

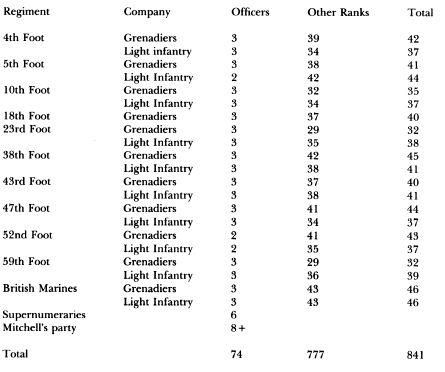

These lists indicate the following numbers of “effectives” as of April 18, in the companies that marched to Lexington and Concord:

There may have been as many as seven additional members of Mitchell’s party, and perhaps another 60 Marines, if the 1777 rosters are correct, and Loyalist volunteers, minus one straggler at the Phips farm. The size of the Concord expedition might therefore have been as large as 909 officers and men. If so, the rejected estimate of John Boyle proves to be the most nearly accurate.

Are the muster rolls a trustworthy source? For the 23rd Royal Welch Fusiliers they can be tested against the diary of Frederick Mackenzie, who reported that the number of rank and file under arms on April 19 was precisely the same to the man as the estimate that emerges from the rosters. Gage and Haldimond established elaborate procedures to ensure accurate and honest reports, and were successful.

There is only one possible source of error. These estimates assume that the proportion of men who were ill, absent, on detached duty or otherwise “ineffective” was the same on April 19 as at the date of the preceding roster (

circa

Jan. 30, 1775). There was some attrition in Gage’s army during the entire period. From January to June, net attrition other than losses in combat totalled only 1.9% for the rank and file in all companies of every marching regiment. A special effort was made to keep up the strength of grenadier and light infantry companies by transfering men from the line companies (Barker,

British in Boston,

58-59). Even the mean attrition rate of the garrison as a whole would reduce these estimates by only 15 men. For flank companies, the wastage was smaller, and the net change may actually have been in the opposite direction, as men on detached duty returned to their units when they went on active service.

The sources for these estimates are Regimental Rosters in WO12, PRO. Cf. Barker,

British in Boston,

31; W. G. Evelyn to his father, April 23, 1775, Scull,

Evelyn,

53; an anonymous light infantryman in

Letters on the American Revolution,

187—200; Pope,

Late News,

entry for April 18, 1775; French,

Day of Concord and Lexington,

73; Murdock,

The Nineteenth of April,

47; Tourtellot,

Lexington and Concord,

104; Gross, Minutemen

and Their World, 115

.

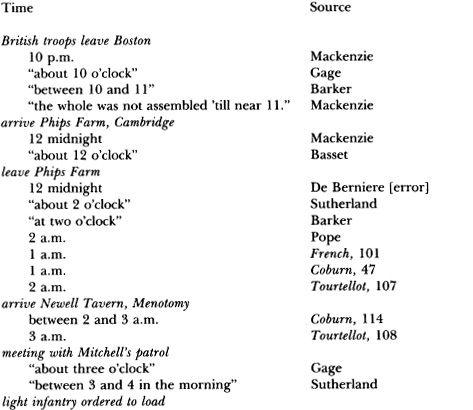

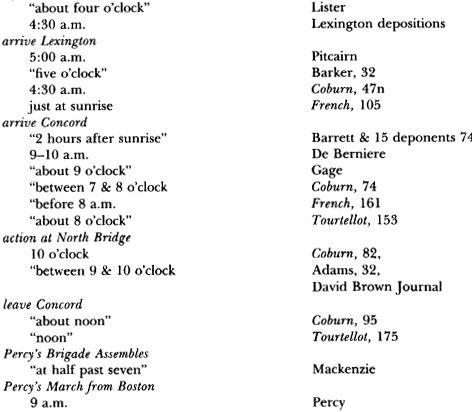

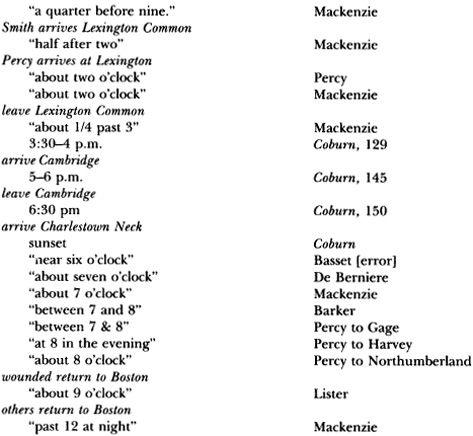

APPENDIX L

A Chronology of the British March, April 18-19, 1775

A Chronology of the British March, April 18-19, 1775

Many contemporary estimates are available for the chronology of the British expedition. With allowances for a range of variation in individual timepieces, they roughly agree. But several historians have rejected them. The first to do so was Frank W. Coburn, who in general revised the estimates of participants, assigning earlier times for the British march to Concord, and later times for the return. Allen French followed Coburn, but sometimes blurred individual events where discrepancies were specially apparent. Arthur Tourtellot was erratic, but tended to split the difference between Coburn’s estimates and those in primary sources. These historians, who shared the general opinion that Smith was “very slow,” could not believe that the British march was as rapid as contemporary estimates indicated.

This inquiry finds that the estimates of eyewitnesses were generally consistent, and the speed of the march was compatible with their descriptions of it. Further, a comparison of solar times with their estimates of the relationship of sunrise and sunset to events of the march confirms the accuracy of participant-observations. Coburn, French, and Tourtellot all followed one another into error on this question.

In the following variant estimates, primary sources are given in roman type; secondary estimates in italics.

APPENDIX M

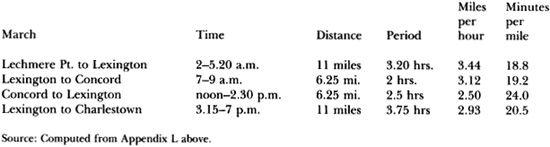

The British March: Time, Distance, Velocity

The British March: Time, Distance, Velocity

APPENDIX N

Methods of Timekeeping in 1775

Methods of Timekeeping in 1775

Where clock time was given, it differed from the temporal conventions we keep today. Since 1883, Boston has run on Eastern Standard Time, which was invented to synchronize railroad timetables. In 1775, watches and clocks were commonly set by sunlines at high noon, or by what is called today local apparent solar time.

All estimates in this work should be understood as an approximation of local apparent solar time, not Eastern Standard Time. To convert from local apparent solar time to Eastern Standard Time in the longitude of Boston, one must subtract 25 minutes. If Paul Revere left Charlestown at 11:00 p.m. local apparent solar time, the equivalent would be 10:35 p.m. Eastern Standard Time, or 11:35 p.m. Eastern Daylight Time.

American clock-time in many accounts referred merely to the nearest hour. Some American clocks in 1775 had no minute hand. American narratives marked the time not by hours but natural events—sunrise and sunset, or the rising of the moon. One event was recorded as happening between first light and sunrise.

British officers tended to observe clock time and often used fractions of hours and even minutes. Elijah Sanderson, the Lexington man who was captured by the British patrol later testified, “They detained us in that vicinity till a quarter past two o’clock at night. An officer, who took out his watch, informed me what the time was” (Phinney,

Lexington,

31).

Neither side appears to have synchronized watches, a practice that appears to have begun among Union armies in the west during the Civil War. In other wars during the 20th century, opposing sides set their clocks differently. This was not the case at Lexington and Concord. In some instances, British estimates of times tended to be later than those of the Americans. But the difference was small and inconstant.

One test of the accuracy of temporal estimates can be made by comparing hours of sunrise and sunset with primary estimates of the chronology of events. Many eyewitnesses on both sides wrote that the Regulars arrived at Lexington Green just at sunrise. They also agreed that the battle ended when Percy’s brigade crossed Charlestown Neck at sunset. These events may be used to assess time-keeping by participants and historians. In general they confirm the accuracy of estimates by participants, and contradict the revisions that were introduced in the literature by Coburn, French, and in some cases by Tourtellot. On April 19, 1993, the hours of sunrise and sunset were as follows: