Paul Revere's Ride (59 page)

Read Paul Revere's Ride Online

Authors: David Hackett Fischer

Tags: #General, #Biography & Autobiography, #History, #United States, #Historical, #Revolutionary Period (1775-1800), #Art, #Painting, #Techniques

In the mid-19th century, cities and towns throughout Massachusetts began to commemorate Paul Revere in their place names. Boston’s May Street became Revere Street in 1855. Other Revere streets appeared in the towns of Arlington, Cambridge, Chelsea, Everett, Hudson, Hull, Lexington, Maiden, Medford, Milton, Quincy, Sudbury, Weymouth, Winthrop, and Woburn. In 1871, the entire Boston suburb of North Chelsea took the name of Revere. Many other places were so named in New England, but few in the nation at large. Paul Revere was still mainly a regional hero.

18

The Union in Crisis: Longfellow’s Myth of the Lone Rider

The Union in Crisis: Longfellow’s Myth of the Lone Rider

In the year 1861, Revere’s reputation suddenly expanded beyond his native New England. As the nation moved toward Civil War, many northern writers contributed their pens to the Union cause. Among them was New England’s poet laureate, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, who searched for a way to awaken opinion in the North. On April 5, 1860, Longfellow suddenly found what he was looking for. He and his friend George Sumner went walking in the North End, past Copp’s Hill Burying Ground and the Old North Church, while Sumner told him the story of the midnight ride. The next day, April 6, 1860, Longfellow wrote in his diary, “Paul Revere’s Ride begun this day.” Two weeks later he was still hard at work: “April 19, I wrote a few lines in ‘Paul Revere’s Ride.’ this being the day of his achievement.” Perhaps on that anniversary day he found his opening stanza, which so many American pupils would learn by heart:

Listen my children, and you shall hear,

Of the midnight ride of Paul Revere,

On the eighteenth of April, in Seventy-five;

Hardly a man is now alive

Who remembers that famous day and year.

Not so well remembered were the lines near the end, that summarized the larger purposes of the poem:

For, borne on the night-wind of the past,

Through all our history to the last,

In the hour of darkness and peril and need,

The people will waken and listen to hear,

The hurrying hoof-beats of that steed,

And the midnight message of Paul Revere.

The poem was first published by

The Atlantic

in January 1861. It had an extraordinary impact. The insistent beat of Longfellow’s meter reverberated through the North like a drum roll. It instantly captured the imagination of the reading public. This was a call to arms for a new American generation, in another moment of peril. It was also an argument from Paul Revere’s example that one man alone could make a difference, by his service to a great and noble cause.

From an historiographical perspective, Longfellow’s poem contained a curious irony. He appealed to the evidence of history as a source of patriotic inspiration, but was utterly without scruple in his manipulation of historical fact. As an historical description of Paul Revere’s ride, the poem was grossly, systematically, and deliberately inaccurate. Its many errors were not merely careless mistakes. Longfellow did some research on his subject. He consulted amateur scholars such as Sumner, probably knew Frothingham’s

Siege of Boston

and George Bancroft’s

History of the United States,

which had sold very briskly only a few years before, and appears to have been familiar with Paul Revere’s account, which had been in print for sixty years. To enlarge his stock of poetic imagery, Longfellow climbed the

steeple of the North Church, scattering the pigeons from their roosts in his search for color and detail. Even the pigeons went into the poem for a touch of verisimilitude.

19

Having done all that, Longfellow proceeded to change the history of Paul Revere’s ride as radically as his poetic predecessor Eb. Stiles had transformed its geography. His most important revision was not merely in specific details that he so freely altered, but in a new interpretation that had a powerful resonance in American culture.

For his own interpretative purposes, Longfellow invented an image of Paul Revere as a solitary hero who acted alone in history. He allowed his mythical midnight rider only a single henchman, an anonymous Boston “friend” who appeared in the poem as a Yankee Sancho Panza for this New England knight-errant. Otherwise, Longfellow’s Paul Revere needed no help from anyone. He rowed himself across the Charles River, waited alone for a signal from the Old North Church, made a solitary ride all the way to Concord, and awakened every Middlesex village and farm along the way.

As a work of history, that interpretation was wildly inaccurate in all its major parts. But as an exercise of poetic imagination it succeeded brilliantly. Longfellow’s verse instantly transformed a regional folk-hero into a national figure of high prominence. Paul Revere entered the pantheon of patriot heroes as an historical loner of the sort that Americans love to celebrate.

From Captain John Smith to Colonel Charles Lindbergh, many American heroes have been remembered in that way, as solitary actors against the world. This was not entirely an American phenomenon. It was an attitude that belonged to a time as well as a place. Many Romantic writers in the late 19th century—Emerson, Carlyle, Nietzsche—celebrated world-historical leaders as heroic individuals who faced their fate alone. That idea had powerful appeal in a world that was becoming more ordered, and more institution-bound. The genius of Longfellow’s poem was to link this powerful theme to a patriotic purpose. It stamped its image of Paul Revere as an historical loner indelibly upon the national memory.

New England antiquarians responded to Longfellow’s poem with expressions of high indignation for its gross inaccuracy. Charles Hudson, town historian of Lexington, Massachusetts, wrote angrily in 1868, “We have heard of poetic license, but have always understood that this sort of latitude was to be confined to modes of expression and to the regions of the imagination, and should not extend to historic facts … when poets pervert plain matters of history, to give speed to their

Pegasus,

they should be restrained, as Revere was in his midnight ride.”

20

For many years historians in New England labored to correct Longfellow’s errors. They demonstrated exhaustively that Paul Revere did not receive the lantern signals from the Old North Church, but helped to send them. They documented abundantly the fact that he did not row alone across the Charles River, but was transported by others. They proved conclusively that Paul Revere did not reach Concord, and that another messenger succeeded where he failed. Other midnight riders were much discussed: notably Dr. Samuel Prescott, and William Dawes, who began to receive more attention than Paul Revere himself.

But the scholars never managed to catch up with Longfellow’s galloping hero. Generations of American schoolchildren were required to memorize Longfellow’s poem. Even today many older Americans are still able to recite stanzas they learned in their youth, long after their memory of more recent events has faded. Whatever the failings of the poem as an historical account, it gave new life and symbolic meaning to its subject. It also elevated Paul Revere into figure of high national prominence, and made the midnight ride an important event in American history.

Longfellow’s interpretation of Paul Revere was taken up by many popular writers who came after him. Several generations of American artists also borrowed Longfellow’s theme of the lone rider. Howard Laskey in 1891 did a drawing called “The Ride,” in which Paul Revere and his galloping horse appeared entirely alone, floating in an empty space with nothing in sight but their own shadow.

21

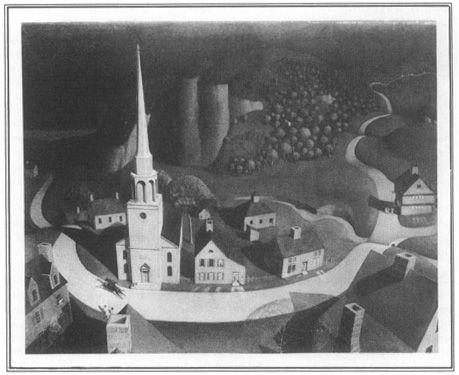

Grant Wood in 1931 did a striking painting of “The Midnight Ride of Paul Revere,” (1931), which gave the same interpretation a different

twist. The midnight rider appeared as a dark, faceless, solitary figure, galloping alone through an eery New England townscape that appeared sterile and lifeless in the brilliant moonlight.

Grant Wood,

Paul Revere’s Ride,

1931. The painter gives us a new version of Longfellow’s myth with a 20th-century twist. Paul Revere appears as a lone midnight rider, galloping across a sterile, soulless American landscape. (Courtesy, Metropolitan Museum of Art and VAGA, Inc.)

Longfellow’s interpretation was given a new form in 1914 by Thomas Edison, who made a silent film called “The Midnight Ride of Paul Revere.” Like many autodidacts, Edison was deeply contemptuous of schools and scholars. “I should say,” he wrote, “that on the average we only get about two percent efficiency out of school books as they are written today. The education of the future as I see it, will be conducted through the medium of the motion picture, a visualized education, where it should be possible to obtain a one hundred percent efficiency.” To that end, Edison made a film of Paul Revere’s ride as a way of teaching American history through the camera. His interpretation closely followed Longfellow’s poem in substance and detail—myths, legends, errors, pigeons and all.

22

Myths for Imperial America: Colonel Revere as a Man on Horseback

Myths for Imperial America: Colonel Revere as a Man on Horseback

Thanks largely to Longfellow’s poem, Paul Revere’s stature increased steadily during the late 19th century, and spread throughout the United States. Towns were named after him not merely in New England, but also in Pennsylvania, Minnesota, and Missouri.

The centennial celebrations of the American Revolution that began in 1875 also inspired much popular interest in his life and work. Many celebrations were held in that year,

when President Ulysses Grant himself came to Lexington and Concord. The Old North Church began to keep the custom of its annual “lantern ceremony.”

The Paul Revere of the late 19th century began to be given a new persona, that was thought to be more meaningful in a different era of American history. During this period he was commonly called Colonel Revere, the military title that came to him later in the War of Independence. Increasingly he became a militant symbol of American strength, power and martial courage.

In 1885 the city of Boston decided that this man on horseback needed an appropriate equestrian monument. It sponsored a prize competition that was won by an unknown young artist named Cyrus Dallin, an American sculptor who later came to be widely known for his muscular Puritans, melancholy Indians, heroic pioneers, and courageous soldiers of the Civil War. Dallin’s monumental Paul Revere was the proverbial man on horseback, a militant figure standing straight up in his long stirrup leathers, in a costume that was cut to resemble a Continental uniform. The midnight rider appeared as a strident symbol of American power, with bulging muscles, a military appearance, and a murderous expression. To complete the effect, even the horse was transformed. Deacon Larkin’s mare Brown Beauty suffered the indignity of being changed into a stallion, and given the head of a Greek war horse, and the body of a Renaissance military charger.

There was an interpretative problem in the first design of Dallin’s sculpture. It was called “Waiting for the Light,” and showed Paul Revere in Charlestown, looking back toward the Old North Church for the lantern signal.” The committee liked the conception, and awarded its prize to Dallin. But critics forcefully pointed out that the interpretation was an error borrowed from Henry Wadsworth Longfellow. Dallin was sent back to his studio, and produced another version of Paul Revere, as militant as before, but without Longfellow’s errors. The ensuing controversy, however, destroyed the momentum for the project, and the money could not be found to construct a full-scale bronze statue. Dallin’s sculpture remained a plaster model for many years, which he redesigned at least seven times. But even in its unfinished state, it captured the spirit of yet another myth of the midnight rider. In this latest incarnation, Paul Revere became less a man than a military monument. He was made to personify the new union of power and freedom in a Great Republic that was beginning to flex its muscles throughout the world.

23