PERFECT YOUTH: The Birth of Canadian Punk (17 page)

Read PERFECT YOUTH: The Birth of Canadian Punk Online

Authors: Sam Sutherland

Goddard’s use of the somewhat titillating, Roger Corman–ish slumber party imagery speaks to the different approaches taken by the B-Girls and the Curse. Between the two bands, tension built, the result of two distinct methods of attacking the male-dominated dominion of the Horsehoe Tavern stage. Even decades removed from their initial time in the Toronto spotlight, both offhandedly dismiss the other for either being “like guys in girls’ bodies” (the Curse) or “groupies who decided to be a band” (the B-Girls).

The Curse was without a doubt a more typically

masculine explosion of punk energy, with the B-Girls more conscious of using their femininity to draw in their audience, but both are equally valid methods of creative expression, and, most importantly, both bands were doing exactly what they wanted to be doing. No one told the Curse or the B-Girls to behave one way or another. Their act was all them, making it a true expression regardless of outside perception. Once again, it is the

Star

’s Goddard who provides a fitting juxtaposition of the two, this time in a mid-’78 feature about the best bands in Toronto “waiting to be discovered.” He writes,

The B-Girls are everyone’s ’50s-style dream date. The Curse just plays — not very well a year ago, but much better now. What’s more, these four women don’t mind letting their usually-mostly-male audiences know that they are women — real women, not male visions of what’s real.

Both bands travelled to New York extensively. The Curse, having started earlier, imploded first. Their final show occurred onstage at Max’s Kansas City, right before the legendary venue closed its doors for good. But tensions in the band were making everyone miserable.

“I was a diva,” says Skin. “And the rest of the girls wanted to get a woman who was my boyfriend’s ex-girlfriend to manage to band. On top of that, they were going to change the band name to True Confessions. I just said, ‘You can fuck right off, because I’m in the Curse. If it’s not the Curse, I’m not in it.’” The band changed its name. Skin was no longer in it.

The B-Girls fared better in New York; Cynthia Ross was soon dating — and eventually engaged to — Dead Boys frontman Stiv Bators, and the band decided to relocate to the city full time. In the process, they lost both Cynthia’s sister and Lucasta.

“I didn’t want to live with cockroaches,” says Lucasta, who had already spent time in the city while dating Arturo Vega, the legendary artist behind the Ramones’ iconic logo. “I knew it wasn’t for me. I didn’t want to make the move, and I didn’t like our chances. I didn’t want to be a New York band that didn’t make it. I didn’t want to live in poverty.”

“She had an amazing voice, so it was a real loss,” says Cynthia. “But we gelled better after and became a real rock band. The reality is that you’re not going to be making any money. It’s hard. My sister was given a choice by her boss, the job or the band. She choose her job. You can’t blame people.”

The B-Girls spent their first month couch surfing and crashing in the old New York Dolls’ rehearsal space, but things seemed to be paying off; they produced a set of demos with Debbie Harry from Blondie, opened for Elvis Costello, and found themselves unlikely friends with the Clash.

“We opened for the Ramones and the Dead Boys at

CBGB, and [New York Dolls guitarist] Sylvain Sylvain came up to me and said, ‘Two guys from the Clash want to talk to you,’” says Ross. “They said they liked us and wanted us to open for them, and I just assumed it was a pick-up line. They asked for my address and my telephone number. I got a telegram from their manager saying, ‘Get passports.’ I didn’t believe it.” The B-Girls were invited to spend a week with the band in England, but when drummer Topper Headon broke his arm, the tour was cancelled. When Joe Strummer promised to make it up to the band, Ross assumed it was just a kindness, and that the opportunity had passed them by.

They ended up opening for the Clash across North America, playing the final rock concert at the O’Keefe Centre in Toronto, when rioting fans tore out seats and caused thousands of dollars in damage. In its wake, Mick Jones produced another demo for the B-Girls, further adding an important boost of credibility as they searched for a record label.

They fielded numerous offers, but turned them all down. Debbie Harry had warned Ross that managers and labels would be eager to remake the B-Girls as their own girl-group fantasy, something she had fought against in Blondie for years. The band took her advice to heart, and ended up letting every deal that floated their way pass by.

“What Debbie said was true,” says Ross, who still counts Harry amongst her closest friends. “Most of the people who were up there in the record industry were men. When they see four not-bad-looking young women, they think they can

make you into their fantasy. The Runaways didn’t play on their first record. The Go-Gos didn’t. That’s why we didn’t

sign. They’d bring in session guys to do it, and we didn’t want

that. We were who we were, and we weren’t perfect. Punk wasn’t about being perfect.”

As offers began to dwindle, it became clear that the B-Girls had run their course. The band still created a few great opportunities, the kind that only arise through playing rock and roll all over North America. One of the strangest was a decidedly creepy meeting with lifetime inspiration Phil Spector, who sent two scouts to check out the band at a show in Los Angeles. He requested a private meeting with Ross. She left the weirdo recluse’s mansion feeling “really scared.” In hindsight, Ross was probably right on the money.

The B-Girls were done. Unwilling to compromise the identity of the band in the name of a major label deal that could leave them out in the cold as Harry had warned, they opted to dissolve the band. It’s an unfortunate end, and a clear demonstration that, as much as punk had succeeded in breaking down some of the gender exclusivity of rock and roll, it could only effect change within a localized area. On a micro level, it might have been possible for female musicians to participate on the same plane as their male counterparts, but outside of the comfort of that alternative community, the old rules still applied, and punk couldn’t do anything to change the worldview of a 50-year-old A&R rep for CBS in the ’70s. This doesn’t diminish the value of those changes that occurred on a citywide level across Canada, because it is there that substantial social change starts to form. Speaking to women from across the country, there seems to be no definitive answer as to whether or not the promise of punk has been delivered on, 30 years later.

“The music scene was so different then because there were so few women playing instruments in bands,” says Jade Blade, of Vancouver’s the Dishrags. “It also meant we got a lot of gigs because people wanted an all-girl band on the bill and people would come to see us. It was like being a rare animal at the zoo. It’s come a long way since then, but it’s still mainly the front-people who constitute the female part of the band.”

“I think there was a sense that you felt like they weren’t taking you seriously, like you were a novelty act,” says Lori Hahnel, of Calgary’s the Virgins. “Kind of like, ‘Oh, it’s an all-chicken band.’ I’m not certain that attitude no longer exists, but it’s certainly not as bad as it used to be. I mean think of the environment you’re talking about. To give it context: Farrah Fawcett was a cultural icon. I think it’s better now.”

“I don’t think it’s changed much,” says Mickey Skin. “There’s a lot more women who are musicians, and they don’t get the breaks that they should. The ones who do break through have to be so strong. And when women are strong like rock stars, they’re sluts and whores.”

“I think it’s gotten worse,” says Cynthia Ross. “I look at the female acts that are making it, and it seems like they’ve been created by a PR firm.”

It’s hard to draw a neat conclusion here. While there is absolutely no doubt that female involvement in punk, as compared to other rock subgenres, was exponentially larger, more involved, more accepted, and more influential, the fact that so many of the scene’s key players still feel as if they were often treated unfairly speaks to the ongoing need for vigilance in these areas. That almost everyone agrees that things have either not changed, or, worse, become even more closed to female involvement, is disheartening.

It seems like punk opened up rock and roll to women on a technical level, as bands emphasized aesthetic and attitude over virtuosity, anyone enthusiastic enough to start a band was welcome to perform. This allowed groups that had traditionally been ostracized from rock-based musical circles — women, anyone not middle class — a chance to break into the previously secret and sacred (and wealthy and masculine) world of live rock and roll. In addition, it was a genre with an intense focus on aesthetics, and in cities like Toronto and Regina, women ran the clothing stores that provided all the punk attire that defined the scene’s entire look, a crucial component of the nascent, highly visual movement. But despite these doors being opened to female performers and involvement, dominant patriarchal attitudes still existed in the punk scene, and especially in the music industry as a whole.

Many of us would like to imagine the punk community as a proper alternative to mainstream culture, one in which dominant ideologies of exclusion are not just unwelcome, but simply not present. But pervasive social mores are truly massive and hard to ignore, and even punks can bring mainstream ideological baggage into the practice space. Punk, in theory, offered the promise of a different approach. It didn’t deliver, because its practitioners were still imperfect people who were raised in a profoundly sexist society.

But fuck, some people tried.

D.O.A. AND THE EARLY VANCOUVER SCENE

The Dishrags [© Bob Strazicich]

November 27, 2000, 8:00 p.m. PST

On the eve of Canada’s 37th federal election, the polls have finally closed in Vancouver, B.C. Joe Keithley is with his family, watching the early returns. This is his third time running for public office, and first time on a federal level. Since the ’70s, Keithley has been a vocal supporter of radical political causes in his hometown, and has used his band D.O.A. as a platform to raise money and awareness for different organizations over their decades-long career. Running as a Green Party candidate for federal parliament is only the next logical step in a career comprised of bold leaps, from fighting cops at the Republican National Convention in 1980 to touring behind the Iron Curtain in 1984. One of the greatest barriers to Keithley breaking through as a legitimate candidate is his lifelong punk name: Shithead. But tonight, Keithley will receive 15% of the popular vote in his riding. He won’t win, but he will be the country’s most successful Green Party candidate. And almost everyone will go on calling him Shithead.

D.O.A. is the most famous name contained within these pages. They’ve stayed together the longest, produced the most records, played the most shows, written the most books, and had the most measurable influence on the international punk scene of any Canadian band. Along with the Subhumans, they’re the sole Canucks given any ink in Stephen Blush’s iconic history of the ’80s hardcore scene,

American Hardcore

.

That’s because D.O.A. wrote the first record to use the term “hardcore.” It had been floating around the scene for a few months, but when D.O.A. released

Hardcore ’81

, they made it official, giving a tangible identity to a new movement. You either recognize this as being a huge fucking deal, or you need to trust this description: it was a huge fucking deal. Hardcore was still a new offshoot of punk, a rejection of the frills of a genre that itself was a rejection of the frills of rock and roll. It was also a distinctly North American genre; punk had been conceived somewhere between New York City and England, but by the time it got to the west coast of America, it already sounded bloated and pretentious. So new bands emerged, more violent and primitive than the Sex Pistols could have dreamed. And while it’s true that hardcore is a near-pure American art form, it still got its name from a couple of heshers from the interior of British Columbia.

Since effectively defining a worldwide musical phenomenon, D.O.A. haven’t stopped. They’ve continued to release new music, to tour the world, and put their money where their mouths are when it comes to political activism, living up to their slogan of “Talk – Action = Zero.”

Which makes a chapter on D.O.A. a really hard one. The history is already out there. Not only does Joe “Shithead” Keithley, the band’s lone consistent member and creative driving force, have two books of his own, but the band’s history is still being written. In 2008, they released

Northern Avenger

, one of their best albums since that hallowed ’81 landmark, and in 2011, Keithley wrote all the music for a new stage adaptation of Michael Turner’s classic Canadian punk poem-cum-novel

Hard Core Logo

. Many of the bands featured in this book flamed out a few months after they formed. D.O.A. is like a terrifying wildfire that lingers in the hills for decades.

For that reason, this chapter is as also an examination of the foundation of the Vancouver scene and the importance of the Furies and the Dishrags, the first two punk bands on the west coast. The members of D.O.A. started playing music in B.C., but left for Toronto and what they assumed to be greener pastures in 1978. Courtesy of the thankless work of the Furies, they were wrong, and when they finally returned to Vancouver, they found a city bursting with passion and punk, the perfect place for them to put down roots and develop the hyper-political, extra-lean incarnation of punk rock that they helped to pioneer.

The world needed D.O.A. But D.O.A. needed Vancouver.

It’s the middle of a dreary February day when I get a hold of Chris Arnett, Vancouver’s de facto first punk. It’s frigid, dark, and snowing outside of my window. Arnett still lives in B.C., transplanted to Salt Spring Island, part of a cluster of populated islands off the mainland coast near Vancouver. As we talk, he sits in his house, watching a cool mist roll in off the ocean. I watch the snow pile up outside my own window. When Arnett says, “Don’t ever come here, you’ll just end up moving,” I believe him.

Arnett formed the Furies in early 1977 Vancouver. The band was literally the only punk band in the city; when the opportunity to play a show was presented to them, there was no one in the city to open. The only person Arnett could think of was his 15-year-old cousin in Victoria.

“I knew she was into music,” he says. “And her friends, they were into cool music. So she got a guitar, and I taught her how to play. We needed a band, so I went over to the island and asked if they wanted to play. The day of the show, we were rehearsing in West Van and they came over. They said, ‘We can’t rehearse while you’re watching.’ So we went upstairs and they started playing, and it was like, ‘Fuck, they’re better than we are!’ They were great, they had a great attitude.”

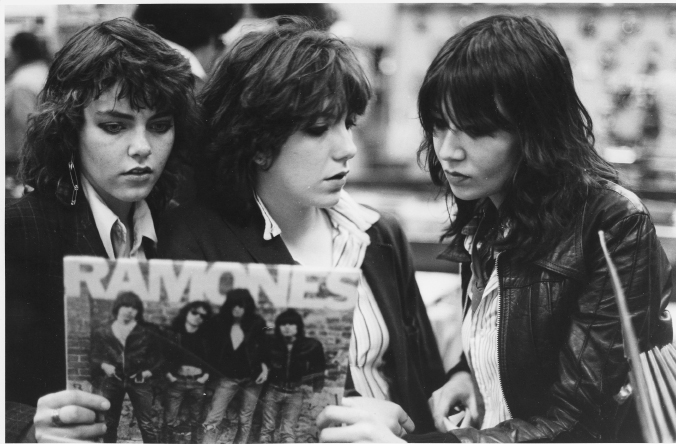

“I was always taking his recommendations for stuff to listen to,” says Jade Blade, Arnett’s kid cousin and co-founder of the Dishrags, effectively the city’s second punk band. “He formed a punk band around the same time we got interested in the Ramones, so it just all came together. We had two or three weeks to get a set ready, and it was really exciting to rush into all of that. We hadn’t practised all that much and it was very, very raw and a lot of fun. Totally nerve-wracking. I mean, we were 15 at the time. For three girls from the countryside to come to the big city . . . I’ve gotta say, it was exciting.”

Naturally, everyone involved was unsure about what to expect. Graffiti all over the city advertised in big, sloppy letters, “Punk comes to Van!” But as a totally unproven musical commodity, the bands and organizers were left to wonder if anyone would come to see two brand-new acts at the Japanese Hall (the only public Japanese building not seized by the B.C. Government during the Second World War). About 400 people showed up.

“It was a really interesting mixture of people,” says Arnett. “There was a tentative feeling in the air, like, ‘Is this all gonna work?’ People were so used to going to these choreographed clubs where there’d be all these long-haired guys with tons of equipment, and it just intimidated the hell out of you. We were doing the exact opposite.”

“I remember thinking that the audience was really kind of bizarre,” says Blade. “There were parents, and there were long-haired hippies, and then a few art-school types who got decked out for it in early punk gear.” The Furies, who had been practising endlessly in preparation, had 21 originals to play, closing out their set with a cover of “Raw Power” and a 45-minute version of the Velvet Underground’s “Sister Ray.” The Dishrags opened the show with a set of Ramones covers, and then continued to play into the night after the Furies had finished, providing a perfectly sloppy soundtrack to the celebratory first night of Vancouver punkdom.

“My cousin, my aunt, and uncle were standing in the doorway, waiting to take the Dishrags back to Auntie’s house in the city,” says Arnett. “I got a ride with them, and I remember people saying, ‘Oh, you’re a real punk, driving home with mommy and daddy,’ and I was just like, ‘I have to get home, you fucking asshole.’”

The Furies had played in an art gallery as a warm-up a few weeks prior, but that night in May 1977, when Arnett met Blade and the rest of the Dishrags at the ferry to drive them to the hall, is the first official punk concert in Vancouver history. Given how things progressed, it’s as if Ferdinand Magellan had a more adventurous kid brother, Steve Magellan, who actually lit out around the world first, but just never got any credit for it. Because the Furies found it impossible to get a foothold in Vancouver, despite the fact that an explosion of punk and hardcore was brewing just below the city’s streets. They played live only a handful of times, recorded a demo that wouldn’t be released until the ’90s, and were eventually pulled apart by the frustration of being the only punks in the entire city, completely isolated from the rest of Canada by a massive mountain range.

The Furies recorded a demo that summer, but couldn’t find anyone to get behind a proper full-length album, as interest in punk had yet to catch on in the city. The Ramones visited for the first time in July, which helped hasten the scene’s development, but the Furies weren’t long for this world. Both Jim Walker and John Werner, the band’s rhythm section, decided to move to England; Walker would end up playing in Public Image Ltd, John Lydon’s post–Sex Pistols outfit. The Furies’ final show occurred on September 4, 1977. When one band cancelled, another jumped on at the last minute — a bunch of longhairs from the interior called the Skulls.

Joe Keithley spent one term at Simon Fraser University. He thought he was going to be a civil defence lawyer, like his hero, William Kunstler, the man who represented the Chicago Seven against charges of conspiracy in the 1960s. Radicalized in high school by the work of the local Greenpeace chapter in response to the looming threat of the international arms race, Keithley bounced from professional hockey aspirations (he was going to play for the Bruins), to designs on rock stardom (he was going to play with Steve Miller), to the noble pursuit of law (he was going to save the world). Then, he bounced back to rock and roll, dropped out of SFU, and moved to the tiny town of Lumby with a batch of friends from his high school.

Keithley, Ken “Dimwit” Montgomery, Gerry “Useless” Hannah, and Brian “Wimpy Roy” Goble packed up and moved into an abandoned farm and refired their rocker aspirations. Weaned on Sabbath and Zeppelin, the group cycled through names like the Resurrection, the Icon, and Stone Crazy. They were effectively squatting in Lumby, occupying an old homestead called Cooper’s Farm. The band was trying to go all-acoustic, an attempt at off-grid living that Hannah in particular defended adamantly. It lasted four months before, despite Hannah’s protestations, the band sold out and moved into a house in nearby Cherryville, fully tricked-out with working hydro. They decided to go electric and traded in their hippie rig for all the finest rocker trappings.

“We went down to Long & McQuade in Vancouver with a pick-up truck with no cab, threw all the gear in the back, and drove back up to Cherryville, which is about eight hours away,” says Keithley. On the day I reach him, he’s about to take off to hang out with his son, who is on March break and eager to go out and enjoy the perfect spring weather in Vancouver. Keithley is a musical and political institution in his hometown, a two-time candidate for the federal Green Party, author of two autobiographies, and creator of some of the most enduring punk songs of all time, from the anti-Reagan anthem “Fucked Up Ronnie” to the well-timed anger of “Disco Sucks.” All of which makes tales of squatting in a farm without electricity or playing his first show at a wake for a logger in Cherryville, the better and stranger.

“You had all the little kids, all the grandmas, all the aunts,” says Keithley of the wake, the first official show for the Resurrection. “We came out with ‘Back in the U.S.S.R,’ and in the break, our singer Gerry totally fucked it up and it was horrible. The way we got back into it was, you know, like . . .” Keithley pauses and makes an impossibly broken, metallic sound, like an engine that won’t turn over. “It was like a car missing a wheel. After the first three songs, the lady that hired us was like, ‘Would you mind if you boys stopped? People are not really enjoying this.’” It was an unceremonious beginning, and things didn’t get better right away. The band met a guitar payer named Brad Kent through Royal City Foods, a warehouse where several members worked occasionally to make their limited ends meet. That they regularly pissed in the canned corn was not, technically speaking, a part of the job.

With Kent, the band started to take themselves more seriously. A seasoned guitar player with a distinct character, he taught the Cherryville crew how to really play, how to look, and how to behave like a real band. (He may have been the one pissing in the corn.) As Stone Crazy, the new band played their first show in June 1977, at the Grassland Motor Inn in Merritt, a logging town deep in the B.C. interior (and, for movie buffs or anyone who’s just a total bummer, the setting for Atom Egoyan’s

The Sweet Hereafter

). Scheduled to play three sets a night for a week, the band barely made it through their first set before being booed offstage, making sure to tell the crowd to fuck off before departing. Subsequently, they were forced back in front of the crowd to apologize (saving themselves from a vicious logger beating), paid $30, and fired on the spot. Despite being an unequivocal failure, the show featured two critical landmarks — the band covered the Ramones’ “Beat on the Brat,” part of a developing interest in punk that grew stronger every day. And they debuted a very rough, very early incarnation of “Disco Sucks,” an original song that would play a huge part in Keithley’s future success. Still, the band headed back to Cherryville with their collective tail between the dual tailpipes on their truck, and moved to Coquitlam, a suburb to the east of greater Vancouver.

The band missed Vancouver punk’s first night out with the Furies and the Dishrags, but they were at the Commodore Ballroom when the Ramones visited in July 1977. It solidified what everyone was already feeling; that the dinosaur rock they were playing was stagnant, and that something new and exciting was happening all over the world. Stone Crazy ditched the Sabbath covers and became the Skulls.

“Everybody got their long hair cut off and got leather jackets,” says Keithley, laughing a little in hindsight at the concept of punk uniformity. The band scored their first show in White Rock at the Spirit of the Sea festival, where they met Art Bergmann and Buck Cherry, helping inspire the pair to head north into the city proper and kick-starting the creation of both the Young Canadians and the Modernettes. They also succeeded in whipping the entire crowd into a riotous frenzy through their sheer incompetence. More importantly, Keithley learned his first lesson in publicity when he decided to call a writer at the

Georgia Straight

, Vancouver’s alternative weekly newspaper, to report the riot caused by his new band.