Philadelphia's Lost Waterfront (17 page)

Read Philadelphia's Lost Waterfront Online

Authors: Harry Kyriakodis

Made in New York and dedicated on January 11, 1849, the floating Gothic church traveled up and down the Delaware River ministering to seamen whose ships were docked in the Philadelphia area. This was evidently the first floating church in the United States and apparently one of only three ever made. It was a venture of the Churchman's Missionary Association for Seamen, an arm of the Episcopal Church.

The wooden church, ninety feet long and thirty feet wide, rested on the hulls of two barges placed ten feet apart. With sailing flags waving from its seventy-five-foot steeple, it was deemed the most beautiful floating chapel in the world. The

Floating Church of the Redeemer

was so famous that a model of it was displayed at London's Great Exhibition of 1851.

Worshippers often left early due to seasickness, and the chaplain himself sometimes had trouble staying upright during services. The unpowered craft also tipped sideways in high winds and even sank once. By 1853, these problems and rising maintenance costs resulted in its sale. The floating church was towed to Camden, where it was hauled ashore and set on a brick foundation to become the landlocked Church of St. John's on Broadway Street.

The

Floating Church of the Redeemer. Library of Congress

.

A fire devastated the structure in 1868, but its bell is still in existence. Seamen's Church Institute now owns it after having found it via an e-Bay auction. The bell was missing for almost 150 years.

F

OGLIETTA

P

LAZA

Thomas Glenn continued in his “The Blue Anchor Tavern” piece:

At present the great wharves of the Pennsylvania Railroad Company cover the site, and a heedless crowd crosses constantly over the spot where the Founder first set foot on Philadelphia's soil. The curious, however, can still mark, in the grade of Water Street, at the distance of about one hundred and fifty feet north of Dock, a slight depression, which runs from the river to Front Street, marking, doubtless, the shelving bank which formed a pathway over which William Penn travelled from the landing to the Blue Anchor Tavern in the year 1682

.

The “slight depression” is, of course, long gone, as is most of Water Street. Today, Dock Street from Front Street to Delaware Avenue is somewhat north of its original location owing to the upheaval caused by I-95. It was reconstructed atop the concrete cover above the superhighway, as was Spruce Street and Foglietta Plaza.

Little used and rather forbidding, Foglietta Plaza is administered by the Interstate Land Management Corporation. The little greenery of this maze-like courtyard hardly camouflages the ventilation towers and fire suppression equipment required for the tunnel underneath. And the incessant roar of vehicles speeding underground is distracting, if not deafening.

The plaza was named after Thomas Foglietta (1928â2004), an esteemed lawyer and Pennsylvania representative in the U.S. House from 1980 to 1997 (during which time he was involved with enhancing Penn's Landing and the Port of Philadelphia). Later an ambassador to Italy, Foglietta grew up a few blocks south of the plaza, on a street where his grandparents settled upon emigrating from Italy.

Foglietta Plaza lies squarely at the historic location of the mouth of Dock Creek, although the creek had long been buried by the time the courtyard was built. This spot was also the site of the Delaware Avenue Market, built in the mid-1800s and topped by a clock tower. This was the place to go to for fruit and vegetables, with heaps of watermelons, peaches, tomatoes and so forth on sale daily.

Incidentally, Front Street used to go straight through; it was not interrupted at Foglietta Plaza until the courtyard was installed when I-95 came through. So the plaza, in a way, represents how the drawbridge over Dock Creek connected the northern and southern segments of Front Street.

The Delaware Avenue Market at Dock Street in 1914. This building was torn down in the 1960s. Foglietta Plazaâatop I-95âoccupies the space today.

Philadelphia City Archives

.

M

EMORIALS AT

P

ENN

'

S

L

ANDING

The Philadelphia Korean War Memorial is next to Foglietta Plaza. Dedicated on June 22, 2002, and again on October 7, 2006, after being enlarged, this reverential place pays tribute to the 610 servicemen from southeastern Pennsylvania killed or missing in action in the Korean War. The names of those who died are carved into four columns, while etched images on six granite walls portray the war itself. The memorial includes a bronze sculpture of a kneeling soldier, entitled

The Final Farewell

, by Lorann Jacobs.

Close by at Spruce Street is the Philadelphia Vietnam Veterans Memorial, on the concrete cover of Interstate 95. The monument remembers the 646 local residents who lost their lives during the Vietnam War. Scenes from the war and the names of soldiers killed in action are engraved on its two facing walls of polished granite. Dedicated on October 26, 1987, the memorial is sadly forgotten as a visitor's destination, largely because it is a secluded amphitheater. The Purple Heart Memorial, honoring men and women wounded in all American wars, is incorporated into the Vietnam Veterans Memorial.

Foglietta Plaza contains the Philadelphia Beirut Memorial, dedicated on October 20, 1985, to remember Philadelphia's U.S. Marine casualties of the Beirut Peacekeeping Mission killed in the terrorist bombing on October 23, 1983. And across Columbus Boulevard at the USS

Becuna

submarine is a memorial paying homage to Americans lost in World War II submarine combat.

T

HE

L

ENNI

-L

ENAPE AND

W

ILLIAM

P

ENN

(II

OF

II): P

ENN

T

REATY

P

ARK

These modern memorials have their antecedent in the monument that the Penn Society placed by the Delaware River at what is now Penn Treaty Park back in 1827. Still located there, this stone marker is, however, a monument to peace, not war. The Penn Treaty Monument commemorates the “Treaty of Amity and Friendship” between William Penn and local Indian leaders led by Chief Tamanend.

The extraordinary gathering occurred on June 23, 1683, under a giant elm tree (the “Treaty Elm”) at Shackamaxonâan ancient Native American meeting place along the Delaware in present-day Northern Liberties/Fishtown. An interpreter read the deeds that Penn had prepared to the chiefs, who then made their marks. While the treaty itself was probably an informal unwritten pact, it was the primary reason why there was relatively little strife between the Quaker newcomers and the Delaware Indians living in the region.

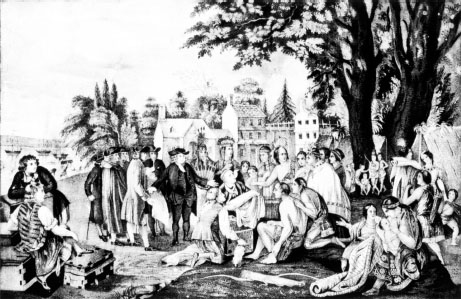

Wm. Penn's Treaty with the Indians

, a Currier-Ives print from about 1845. This is one of countless views of the famous Treaty of Amity and Friendship made alongside the Delaware River between William Penn and local Lenni-Lenape leaders.

The Library Company of Philadelphia

.

Penn paid for Indian land with various goods, which Tamanend divided among his people. The chief then gave Penn a belt made of wampum beads as a sign of friendship. It featured a depiction of two men clasping hands: one large and with a hat (Penn) and the other smaller and hatless (a Native American). The Penn family kept this belt until 1857, when a descendant gave it to the Historical Society of Pennsylvania, which still has it.

The French philosopher Voltaire hailed the 1683 Treaty of Amity as “the only treaty between those nations and the Christian nations which was never sworn to and never broken.” Its imageryâthe Treaty Elm in particularâbecame a worldwide symbol of religious and cultural tolerance and an inspiration to the drafters of the U.S. Constitution.

Native Americans have always respected the location of this legendary event along the Delaware, handing down its story in their oral tradition. They have gathered on numerous occasions at Penn Treaty Park, which was officially established in 1893 as Philadelphia's first recreational park on the edge of the river.

14

D

OCK TO

S

OUTH

H

EAD

H

OUSE

S

QUARE AND A

P

ROGRESSIVE

S

AIL

L

OFT IN

S

OCIETY

H

ILL

These parts were called “South End” in the old days, just as the northern section of Philadelphia was called North End.

T

HE

S

OCIETY OF

F

REE

T

RADERS

In 1682, William Penn chartered the Society of Free Traders to foster commercial development within his Pennsylvania settlement and maritime trade between Pennsylvania and England. The organization was basically a joint-stock company managed by a group of some two hundred affluent English Quakers to whom Penn turned for financial backing in establishing his colony.

The society purchased twenty thousand acres of ground in Pennsylvania and received a charter granting manorial rights, exemption from all quitrents and a choice of waterfront sites in Philadelphia. It also organized and dispatched some fifty ships to Pennsylvania and established a tannery, saw-and gristmills, a brick kiln, a glassworks and a fishery that actually caught dozens of whales (for the oil) in the Delaware Bay. (A beluga whale swam up the Delaware past Philadelphia as recently as 2005.)

While great results were expected, the society's influence diminished, and little came of its efforts. The company folded in 1723, in debt and having irritated many Philadelphia Quakers. Their chief complaint was that the Free Society received favorable treatment from Penn as to the best city plots.

One of those tracts was a 468-foot-wide swath of land between Spruce and Pine Streets from the Delaware River all the way to the Schuylkill River. In a letter written in 1683, Penn described it to society members: “Your city lot is a whole street and one side of a street from river to river, containing near one hundred acres not easily valued.” This territory included high ground overlooking and immediately south of Dock Creek, where the firm set up its local offices and storehouses.

This knoll became known as “the Society's hill.” The name continued long after the demise of the organization itself.

In November 1739, Anglican Protestant George Whitefield preached fourteen sermons over a week from a platform atop the Society's hill. Several thousand people of all religious backgrounds came from far afield to hear the young field minister each day. His commanding voice was heard by men in boats on the Delaware and even two miles away in New Jersey. Whitefield returned the following April, and in later years, to preach from there and elsewhere in Philadelphia.

Benjamin Franklin attended a few of these revival meetings and wound up befriending Whitefield. Franklin was very impressed with the minister's ability to draw large crowds and with his speaking abilities. Whitefield's voice was so expressive that it was said he could move people to tears by how he pronounced the word “Mesopotamia.”