Philadelphia's Lost Waterfront (15 page)

Read Philadelphia's Lost Waterfront Online

Authors: Harry Kyriakodis

It was Samuel Carpenter who built the Slate Roof House about 1687. He had acquired a large lot on the west side of Front Street all the way to Second Street. It was across from his original bank lot, where Carpenter later established Philadelphia's first coffeehouse, Ye Coffee House. He also opened the Globe Inn on this dockside lot. The tavern and the coffeehouse were separated by his bank stairwell.

T

HE

W

HARVES OF

R

OBERT

M

ORRIS AND

T

HOMAS

C

OPE

These were just a few of Carpenter's many landholdings and business dealings in Philadelphia. He became the city's most successful and richest businessmanâthe Stephen Girard of his generationâand later entered into Pennsylvania politics.

Yet he was the first of several Philadelphia merchants who prospered on the riverfront between Chestnut and Walnut. Robert Morris (1734â1806), in his era, came to own the India Wharf along this frontage. (Morris is often called the “Financier of the American Revolution” for his financial dealings in support of the young nation during the Revolutionary War.) His ships and those of other merchant-financiers routinely left there for India and China. Goods imported from those exotic places were stored and sold at Morris's warehouse (called the Indian Stores) in front of the India Wharf.

Quaker merchant Thomas Pym Cope (1768â1854) moved his fledgling shipping business to the Walnut Street Wharf (also called Cope's Wharf) in 1810 and established a successful trade line between Philadelphia and Liverpool by 1822. Another early millionaire and philanthropist by the Delaware, Thomas Cope was both a tough rival and a trusted friend of Stephen Girard.

O

LD

O

RIGINAL

B

OOKBINDER

'

S

Another Samuel (besides Carpenter) made his mark on this block. Dutch immigrant Samuel Bookbinder had opened an oyster saloon at Fifth and South Streets in 1893 and five years later moved his popular eatery to 125 Walnut Street. There, he dished up all manner of seafood, getting his menu fresh off ships docked at the Delaware River. Shad, terrapin and oysters were favorite meals, and portions were generous to satisfy a very masculine crowd ranging from storekeepers and stockbrokers to sailors, sea captains and stevedores.

John Taxin bought the place in 1945 and renamed it Old Original Bookbinder's. During its zenith in the 1950s, '60s and '70s, waiters scurried through paneled rooms adorned with ship models, stuffed game fish and VIP photos. “Bookie's” became a mecca for celebrities, tourists and a regular crowd of Philadelphians. Personalities as diverse as the following always visited whenever they were in town: Howard Cosell, Muhammad Ali, Elizabeth Taylor, David Bowie, Gregory Peck, Julius Erving, John Wayne and Frank Sinatra. Even Madonna dined at Bookie's.

Anyone who was anyone came to Bookbinder's, including presidents of the United States. One day in 1972, the presidential helicopter landed in a parking lot across Walnut Street. (The food warehouses that had been there for ages had just been brought down, and the Sheraton Society Hill Hotel was not yet built.) To the astonishment of regular patrons, President Richard Nixon and Mayor Frank Rizzo had lunch at Bookie's that day.

The cover of a booklet issued about 1960 to promote Bookbinder's Restaurant.

Author's collection

.

The venerable Philadelphia institution closed in 2001 due to financial difficulties and a series of fires. Bookie's reopened four years later after renovations and a new condominium complex attached in the rear, but the restaurant went bankrupt and closed for good in 2009. The set of buildings at 121â135 Walnut Street are now vacant.

13

W

ALNUT TO

D

OCK

P

IRATE

T

REASURE

,

A

T

IMELESS

T

REATY

, T

ROUBLED

T

AVERNS AND A

F

LOATING

C

HURCH

Walnut Street was first referred to as Pool Street since it crossed a pool on a branch of Dock Creek close to Third Street. Walnut was cut off from Delaware Avenue when Highway 95 was builtâa most unseemly consequence of the modern artery. However, a soaring bridge does carry pedestrians over both roadways to Penn's Landing.

M

ILITARY

M

ATTERS

(III

OF

V): T

HE

U.S. N

AVY AND THE

A

LFRED

If the United States Marine Corps can say it got its start at Tun Tavern, then the United States Navy can legitimately say it began a stone's throw away, at the foot of Walnut Street.

In November 1775, the Continental Congress purchased a four-hundred-ton vessel called

Black Prince

from Philadelphia's top merchant shipping firm, Willing, Morris and Cadwalader. (The “Morris” was Robert Morris.) This state-of-the-art ship had been launched the year before in Philadelphia. Congress chose Captain (later Commodore) John Barry to helm the vessel, which became the first flagship of the new Continental navy.

Barry re-rigged the ship as a twenty-gun light frigate renamed

Alfred

. This was the first warship on which a United States flag was hung. The mementous event occurred in December 1775 while the vessel lay in the Delaware off the Walnut Street Wharf awaiting orders to sail. The flag was the “Grand Union flag,” precursor to the Stars and Strips and considered the nation's first national flag. The

Alfred

had a brief but exciting career before it was captured by the British near Barbados in 1778.

Chapter sixteen

will highlight the nation's first naval shipyard, established on Philadelphia's waterfront at the turn of the nineteenth century.

D

OING

B

USINESS ON THE

C

ENTRAL

W

ATERFRONT

Most business in Philadelphia was transacted all along Water and Front Streets on either side of High Street, but mostly on the south.

Robert Morris and other moneyed Philadelphians organized the Bank of Pennsylvania at City Tavern on June 17, 1780. This, the first public bank in the United States, was established on Front Street north of Walnut that July. Its purpose was to borrow money to purchase provisions for the Continental army. The Pennsylvania Bank was never a bank of general deposit, nor was it meant to be permanent. The Continental Congress reconstituted it in 1781 as the Bank of North America, the first corporate banking institution in the United States.

Customhouses, once the main generators of revenue for the United States, were located in all major seaport and river cities. Philadelphia's first U.S. Custom House was at Second and Walnut Streets in the early 1790s. It moved to Front and Walnut in 1795. From 1845 to 1935, the former Second Bank of the United States served as the Philadelphia Custom House. The federal government collected over half a billion dollars in customs revenue through the Port of Philadelphia in the first quarter of the twentieth century. The city's current federal customhouse is a striking edifice at Second and Chestnut constructed in the 1930s.

The American insurance industry began in this area as a consequence of all the foreign shipping and inland commerce conducted in Penn's City. On May 25, 1721, a printer named John Copson opened America's first marine and fire insurance company at his home on High Street near the docks. Until then, all underwriting for risks at sea and other maritime hazards originated in London. Copson was therefore the first insurance agent in America.

Furthermore, the first home of the Insurance Company of North America, now known as CIGNA and still based in Philadelphia, was at the southeast corner of Front and Walnut Streets beginning in 1795.

T

HE

M

ERCHANTS

' E

XCHANGE

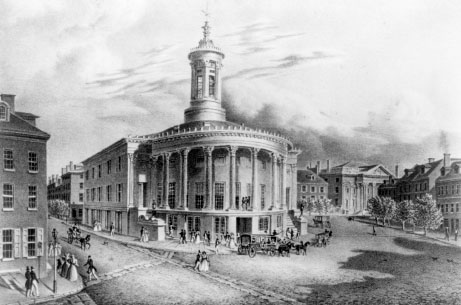

Many marine insurance companies had offices in the Merchants' Exchange, a neoclassic structure still standing at Third and Walnut. It opened in 1834 after a group of Philadelphia businessmenâincluding Stephen Girard just before he diedâorganized to build a proper merchants' exchange for the city. Designed by Philadelphia architect William Strickland, this was the first real trading edifice in the United States.

Real estate and mercantile transactions of all kinds transpired in the central Exchange Room as they preciously had at the London Coffee House and the City Tavern. Not surprisingly, some space was set aside for a coffee shop.

The Exchange Building's semicircular portico was an ingenious adaptation for the odd-shaped lot created by Dock Street. Strickland based its tower on the Choragic Monument of Lysicrates in Athens. It's said that this was because a local newspaper asserted in 1831 that “Philadelphia is truly the Athens of America.” The tower allowed watchmen to scan the Delaware and notify merchants of ships approaching the city, much as Stephen Girard's servants had done from his mansion's high windows and roof. The tower on the Exchange Building today is a replica.

This 1830s print of The Merchants' Exchange also shows Dock Street on the right and Stephen Girard's Bank in the background. That building, formerly the First Bank of the United States, also still stands.

Library of Congress

.

Originally known as the Philadelphia Exchange, this place was the country's financial center up until and during the Civil War. (The entire Northern war effort was essentially financed at this building.) Business activity about that time began moving west to the Broad Street corridor, so the Merchants' Exchange was refashioned as the Corn Exchange. Then, in 1875, it became home to the Philadelphia Stock Exchange. The stately building devolved into a food market surrounded by rickety sheds and produce trucks by 1922. Vendors hawked vegetables from pushcarts, and a gas station was built on the Dock Street side.

The National Park Service acquired the structure in 1952 and maintains offices there. A National Historic Landmark, the Merchants' Exchange is the oldest stock exchange building in America.

W

ORKING ON THE

C

ENTRAL

W

ATERFRONT

At least two sets of riverbank steps were south of Walnut Street. These were probably removed in the late 1800s to allow for the construction of commercial structures between Front and Water Streets. At the same time, long, wide freight depots and tall warehouses were erectedâprimarily by the Pennsylvania Railroadâin that zone east of Front Street.

These buildings serviced a grouping of finger piers and ferry landings owned by the railroad. Piers 10, 11 and 14 South were freight stations that handled coal, lumber and general merchandise carried across the channel to Camden in railroad cars on car floats. Over one hundred men worked at these wharves.

Between Chestnut and Walnut Streets, opposite Ton (Tun) Alley, was Pier 8 South, a covered timber structure owned by the Reading Railroad and used as a freight station for lumber, coal and general goods. Pier 8 was also the principal Philadelphia station of the Reading's Atlantic City division. This was where ferryboats connected with eastbound trains at Kaighn's Point in New Jersey. Next door was Pier 9 South, used by a river-transportation firm that employed barges to move gravel, lumber and general cargo.

The Merchants and Miners Transportation Company used Piers 16, 18, 20, 22 and 24 between Spruce and South Streets as private terminals in connection with passenger and freight service to ports in several states. When the Baltimore-based carrier was liquidated in 1952, roughly one hundred Philadelphia dockworkers lost their jobs.

D

OCK

C

REEK

âD

OCK

S

TREET

Dock Creek was a Delaware River tributary that provided a natural cove or tidal basin to early colonists. Hence its earliest name: the Dock. Called the “Coocanocon” by local Native Americans, it had three branches. The main one flowed northwestward to almost Sixth and Market. The second one went to Washington Square. The third, Little Dock, headed south to where Head House Square is today.