Philadelphia's Lost Waterfront (2 page)

Read Philadelphia's Lost Waterfront Online

Authors: Harry Kyriakodis

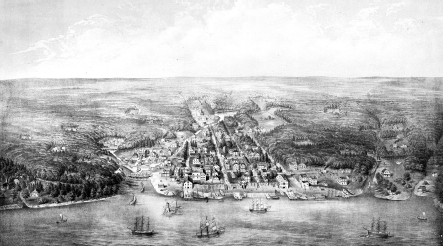

Aerial view of Philadelphia's north central waterfront, circa 1930.

Port of Philadelphia municipal publication

.

The Delaware River waterfront was the axis of the Port of Philadelphia's maritime, commercial and political bustle for some two hundred years after the city's founding. For a long time, when people outside Philadelphia thought about the city, this lively place was what came to mindâand not in a bad way.

This was where wheeling and dealing went on to encourage local, regional and national enterprise. This was where a good amount of the nation's military forces got their start. This was where transportation advances and other inventions were created and exhibited. This was where terrible urban contagions began. This was where early American capitalists made their fortunes. And this was where the individual American colonies were crafted into a nation.

Philadelphia kept its position as America's greatest trade center until the 1820s, when New York's location and financial strength bumped Penn's City to second place. Still, the city's riverfront remained the heart of town.

But as the river district grew increasingly grim and grimy in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, it started to be taken for granted and then became an afterthought. This change in regard was fostered by Philadelphia's relentless push to the west, first to the deforested area beyond Sixth Street in the 1700s, then to the City Hall neighborhood in the 1800s and then to points west, north and south in the 1900s.

As wealthy residents and merchants left the original part of Philadelphia for greener pastures, the Delaware River's edge became forlorn and unattractiveâa forgotten backwater, so to speak, and certainly nothing to celebrate. The river itself practically died before World War II because of pollution, while commerce on and by the water declined dramatically afterward. The mile-wide Delaware, long the city's front door, had shut. An Interstate highway was then run through to seal the deal.

Happily, though, Philadelphia's central waterfront has been receiving attention lately. Exactly three hundred years after William Penn founded his city on the Delaware, work began on refurbishing two abandoned municipal piers at Penn's Landing for residential use. This was the first new housing along the river in over one hundred years. Other activity has followed since then, with multimillion-dollar condominiums and increased recreational, entertainment and dining venues of all sorts drawing money and movement back to this part of town. Penn's Landing has become a citywide gathering place, and even a casino has joined the mix. Philadelphia has finally rediscovered its lifeblood river and the adjoining riverfront.

All told, this is surely the most storied and interesting section of Philadelphia, as it has changed the mostâfor good or badâover time. A strong case can be made that it has changed more than anyplace in America.

1

W

ILLIAM

P

ENN

'

S

S

OLUTION TO A

T

OUCHY

D

ILEMMA IN

1680

S

P

HILADELPHIA

When William Penn founded Philadelphia, the area between the Delaware and Schuylkill Rivers was sparsely populated by tribes of Lenni-Lenape Native Americans (the Delaware Indians), who had inhabited villages along the Delaware for one thousand years. “Coaquannock” was their name for the region, meaning “grove of tall pines.” This referred to the pine forest between the two rivers.

The Delaware Indians fished for shad by the river. These fish were so abundant in the Delaware and Schuylkill that Penn described them in correspondence: “Shads are excellent fish and of the Bigness of our Carp. They are so plentiful, that Captain Smyth's Overseer at the Skulkil, drew 600 and odd at one Draught; 300 is no wonder; 100 familiarly.”

N

ATURAL

T

OPOGRAPHY

At 330 miles long, the Delaware River is the longest free-flowing river east of the Mississippi and the third longest on the East Coast. The river and bay were named after Sir Thomas West (1577â1618), the third Baron De La Warr and first governor of the colony of Virginia. The English erroneously thought that he had discovered the river, but there's no evidence that West ever saw or visited the Delaware. It was actually first explored by Henry Hudson (ca. 1570âca. 1611), who called it “one of the finest, best, and pleasantest rivers in the world.”

Along the Delaware's western bank in Philadelphia, the muddy/gravelly edge of the river originally lapped up to the future location of Water Streetâa rutted lane now mostly gone in the city's old waterfront district. Immediately above this tidal flat was a sheer embankment bluff, between ten and fifty feet high, all along the local shoreline, as the river had scoured a deep channel over the eons. The top of this bluff later became Front Street, the first roadway to parallel the river when Philadelphia was planned.

Some of the city's first settlers actually lived in caves they dug into the embankment, pretty much within the space between where Front and Water Streets came to be. These shallow dugouts, long part of Philadelphia lore and described in

chapter five

, provided the newcomers with their initial shelter upon reaching Penn's settlement in the 1680s.

Water Street developed as the pier-head line during the eighteenth century and provided direct access to the various docks and wharves by the Delaware. As time went on, the riverfront east of Water Street became filled with “made-earth.” (This is the more accurate term for landfill when hard ground is formed by piling soil and rock atop water.)

Wharves were built into the water by employing pilings and casements of logs in the shape of boxes, which were then filled with soil and stone and topped with wooden planks. As the wharves extended eastward, the planks were replaced with a harder surface, like flagstones, Belgian blocks or gravel. This eventually became solid ground, on which port structures were often erected. Docks, piers, ferry landings and the like continually moved eastward into the river in this fashion.

A series of eastâwest alleys cut through this new landscape over time. Commercial structuresâstores, shops, lumberyards, warehouses and shipbuilding facilitiesâwere also built on the made-earth between Water Street and the Delaware.

The embankment steps at Wood Street show how steep the western bank of the Delaware was before the march of time obliterated all traces of the riverside's original landscape.

The terrain at Vine Street had a more gradual descent to the river than that to the southâsay, between Race and Market Streetsâwhere the change in elevation was greater. Therefore, the number of actual steps (treads) composing the Wood Street stairwell is less than that of the other long-gone Penn stairways. That is to say, the other public stairsâwhich no longer existâwere generally more impressive than the stairwell at Wood Street. (The Wood Street Steps are covered in

chapter four

.)

This goes to show that Philadelphia originally had two levels: 1) the main upper plane starting at Front Street and proceeding west and 2) the lower plane beside the Delaware River. This dual set of elevations can still be seen when looking at the city westward from Penn's Landing. The buildings on Front Street are much higher than those on Columbus Boulevard (formerly Delaware Avenue). Penn's Landing here is about thirty feet below the rest of Philadelphia.

In between, at its own varying elevation, is Interstate 95.

M

ERCANTILE

D

EVELOPMENT

William Penn had wanted his “Greene Countrie Towne” of Philadelphia to unfold evenly between the Delaware and Schuylkill Rivers. As part of this plan, he reserved the high frontage along the Delaware for the Proprietary (or Propriety) of Pennsylvania, with land set aside for Penn and his family to use as they saw fit. This space was like the public squares that Penn designated as common parks in the four quadrants of the original city. He further hoped that a promenade with a parapet would stretch atop the length of the Delaware's west bank to provide a pleasing, uninterrupted view of the river from Front Street.

By Smith Cremens & Company, this 1875 lithograph (

Philadelphia in 1702

) sets forth a conceptual panoramic view of Philadelphia twenty years after its founding. The city occupies the space between the mouth of Dock Creek on the left and Pegg's Run on the right. Caves along the embankment and ladders to the top of the bank are visible, as are some early wharves jutting out on the Delaware. Curiously, Windmill Island is missing, although a windmill does appear just about where the long, thin isle should be. The print also contains three small views not shown here: the Penn Treaty, Philadelphia before settlement and the landing of first purchasers.

The Library Company of Philadelphia

.

It's doubtful that Penn long pursued his plan to preserve the high ground paralleling the Delaware River for the purpose of beautifying his city. A practical man, and a shrewd real estate developer at that, he must have realized that shipping facilities had to line the edge of the river if Philadelphia was to become a prosperous commercial metropolis. This would be the only way to accommodate ships transporting merchandise and travelers to the Atlantic Coast and foreign seaports. Penn surely concluded that the riverfront would become exceedingly valuable to the Proprietary.

For all property sold in the Province of Pennsylvania, Penn used the quitrent (or ground rent) system of taxation to provide the Propriety with a steady income. Each land patent stated the annual quitrent amount for the lot. Original settlers (aka “first purchasers”) were charged to pay one shilling for each one hundred acres every year. The collection of ground rents was the cause of much ill feeling between settlers and the Proprietary.

Penn and his agents sold the waterfront lots east of Front Streetâthe “bank lots”âin the 1680s. Affluent buyers, dubbed “bankers,” often subdivided their lots or traded them for acreage deeper in Pennsylvania. Some had bought a thousand or more acres in the countryside and received their city lots as appurtenant to their country acquisitions, together with land in the “Liberties” (Liberty Lands) of Philadelphia County.

William Penn was soon faced with too much proposed and actual development on the Delaware riverfront. Everyone wanted to own prime real estate in the nucleus of Philadelphia, so they clustered by the river. Even more disturbing was that bankers were under the impression that they owned the waterfront abutting their holdings. The bank lot purchasers also claimed the privilege to hollow out space in the high bank next to their lots so as to create “vaults” for use as storerooms. This was the first private versus public conflict concerning the development of Philadelphia's waterfront.

Leading merchant Samuel Carpenter was the first banker to make such a demand. Early in 1684, he asked Penn for permission to “dig cellars or vaults between the Edge of the bank and [his] land provided it be done and kept without prejudice to the Road [Front Street] above.” Penn rejected this request, but Carpenter returned with an even more alarming proposal. He wanted to construct a set of wharves and warehouses on his sizable bank lot between Walnut and Chestnut Streets. Such harbor structures would impede everyone's access to the river for almost a city block.

Carpenter's plan thus generated the first major controversy regarding the use of and access to Philadelphia's Delaware front.

Chapter twelve

has more about Samuel Carpenter, his wharf and his stairs.

W

ILLIAM

P

ENN

'

S

S

OLUTION

In response to all bankers making claims on the east side of Front Street, Penn firmly declared that the riverbank was a common area owned by the Proprietyânot by any banker or other first purchaser. He then softened his stance by offering a compromise. This oft-reproduced language appears in a letter dated August 3, 1684, a few days before Penn returned to England:

The Bank is a top common, from end to end. The rest, next

[to]

the water, belongs to front-lot men no more than

[to]

back-lot men: the way

[Front Street]

bounds them. They may build stairsâand

, [at]

the top of the bank, a common exchange, or walk; and against

[Front]

street, common wharfs may be built freely;âbut into the water, and the shore, is no purchaser's

.

Thomas Jefferson called William Penn “the greatest law-giver the world has produced.” Penn's declaration is an example of his Solomonic wisdom, since he devised a way to balance both public and private interests. He allowed Carpenter and other riverfront developers to build on their bank lots as they desired, but only if they allowed the public to have convenient access to the Delaware.

C

OOL

R

IVER

B

REEZES

Another reason for the mid-block stairways was that Penn wanted to let cool, fresh air from the Delaware River into the hot, congested city. This is echoed by Abraham Ritter in

Philadelphia and Her Merchants

(1860):