Planet of the Apes and Philosophy (29 page)

Read Planet of the Apes and Philosophy Online

Authors: John Huss

One thing that we see in

Rise of the Planet of the Apes

is the keepers at the ape facility behaving just like apes, but apes without

empathy

. And empathy is pretty much a universal trait among apes, including humans, in the right circumstances. The son of the head keeper, Dodge, treats subordinates with violence and cruelty. This is not typical ape behavior, with one caveat. Apes tend not to treat their own troop members this wayâif a dominance competition is over, as we see in the movie, the rest is relatively amiable, although just as with humans there can be bad-tempered and even domestically violent apes. However, apes that encounter members of other

troops, or which are challenged by a competitor for alpha status, can behave this way. Dodge may see the apes as competitors, so he treats them cruelly.

Is Dodge's behavior typical human behavior? Obviously not. Despite Hobbes's claim that “life in a state of nature” would be “nasty, poor, solitary, brutish and short,” anthropologists observe that, except in cases of intertribal warfare, and often even then, humans are not typically violent, and as Stephen Pinker has recently argued, modern humans are even less violent than their ancestors, although this is most likely a cultural, not a biological, shift. In times and societies of plenty, violence is no longer a profitable activity, so we are inclined not to behave that way. This also seems to be true of chimps, as noted before. So despite the message of the film that humans lack empathy and apes are the true moralists, in fact all apes, including humans, are generally not too bad to be around except in extreme circumstances, usually involving competition between groups.

Deference, empathy, social ranks, dominance competition: that's a hefty list of common behaviors among primates. No wonder we make and consume movies about apes to better understand our own human nature!

Taking Caesar as an exemplar, we come to realize that morality is not Kantian alone. A moral primate needs to have not only reason, but also the social dispositions that make morality possible; and even then, morality needs to be scaffolded by socialization and enculturation. Had Caesar never had this upbringing, he may have turned out to be more like General Thade in the 2001 movie.

Just as in the early movies of the 1970s and the first movie of the current reboot, humans are seen as the pinnacle of evolution, in a pigeonhole to which other species will evolve, as humans devolve and lose their dominance through their own mistakes. The filmmakers assume this moral superiority, then invert it to illustrate and illuminate our folly. Thinking about the surprisingly complex philosophical conundrums presented in the

Planet of the Apes

movies not only enhances our enjoyment of the cinematic experience; it helps us understand ourselves better.

Serkis Act

J

OHN

H

USS

T

here's a guy in a spandex suit covered with polka dots. He's got some high-tech gizmo strapped to his head. He approaches a window and presses his face against it. His eyes bulge. His cheeks puff in and out. He pounds his half-open fists against the glass, and emits anguished, non-verbal vocalizations. Now that's what I call acting.

A key frame animator sits before a bank of high-powered computers, channeling performance-capture data through a computer simulation program. It produces a life-like digital image of a chimp with eyes bulging, half-open fists pounding against the window, cheeks puffing in and out. “Hey,” says his boss, “can you make them a little puffier?” He emits anguished, non-verbal vocalizations. Now that's what I call animation.

Should actor Andy Serkis have even been eligible to be nominated for an Oscar for his role as Caesar in

Rise of the Planet of the Apes

? The answer lies somewhere in between these two scenes. It's easy to track down the raw and finished footage on YouTube to make the comparison yourself. Despite a campaign by Twentieth Century Fox and an impassioned blog post by James Franco, once the votes were tallied, Serkis wasn't nominated. But why? Could it be the fierceness of the competition? The nominees for Best Actor in a Supporting Role were: Kenneth Branagh in

My Week with Marilyn

, Jonah Hill in

Moneyball

, Nick Nolte in

Warrior

, Christopher Plummer in

Beginners

, and Max von Sydow in

Extremely Loud & Incredibly Close

(Plummer won).

Perhaps in the eyes of the Academy, given such a strong field, Serkis's performance was simply not Oscar-worthy. Maybe so. But I suspect that at the heart of the (perceived) snub is a performance capture quandary: the status of the art of acting in an age of digital production.

Suppose we try to decide what Serkis deserves by defining what acting is, and seeing whether the chimp performance we see on screen fits the bill. This seems reasonable. And philosophers have been asking “What is

X

?” questions for centuries. My favorite example is Socrates stumping his friend Euthyphro with the question “What is piety?” Eventually Euthyphro simply walks away crestfallenâprobably emitting anguished vocalizations.

Euthyphro was onto something. Twentieth-century philosophy has taught us that we should be suspicious of “What is

X

?” questions. Just because our language allows us to ask them doesn't mean there's a meaningful answer. Ludwig Wittgenstein, the Austrian philosopher, insisted that there are no genuine philosophical problems, only confusions brought about by the questions our language allows us to ask. He felt really passionate about this point, too, going so far as to shake a fireplace poker at fellow philosopher Sir Karl Popper when Popper disagreed with him!

The problem with posing “What is

X

?” questions is that unless we're careful about it, they lead us to seek some essential definition, a set of conditions that

X

, and only

X

, must meet to qualify. For some purposes, this may be fine. In geometry, we want a definition of “triangle” that picks out all and only triangles. Real life is more complicated, and when we go all out in the pursuit of some exact criterion for acting that can be applied to the Serkis case, the real problem slips away from us. We can easily end up defining performance capture as acting or not, right off the bat, before even delving into the matter. The whole point is that with performance capture technology and computer generated imagery (CGI), the definition of acting (movie acting anyway) is in flux. You're not going to solve a problem of definitional flux by simply asserting a definition.

Once you compare the raw and the finished footage of the tearful goodbye scene from

Rise of the Planet of the Apes

, you may be surprised to find that even in the raw footage, Serkis's performance as Caesar is quite believable, and it's easy to see why the studio and his co-star were moved to lobby the Academy on his behalf. Alternatively, you may be surprised to find that Serkis's performance bears only a remote resemblance to that of the Caesar we see on screen, that the artistry and the emotional connection lie not with the performance, but with what the animators have done with “the data.”

I don't have an ape in this race, but obviously many people in the industry do. Blog comments to the posted footage indicate clearly that different people can look at the same footage and see very different things. People who work in animation look at the final clip and see all the marks of key frame animation, a process in which images are created frame by frame either manually or, more often, through the use of a computer program that interpolates some of the frames in between those created by the animator. The relevant question for them seems to be how much of the motion capture data was used to create the final cut. In this particular clip, apparently only data from Serkis's spine was directly used, with the rest of his movements serving as a reference for the animator (in this case Jeffrey Engel of the New Zealand visual effects studio Weta Digital).

In contrast, actors, directors, and fans tend to look at the raw footage and see in it the emotional essentials of the final product already present. They're astonished to see how chimp-like Serkis's movements are. They attribute the bulk of the portrayal to the actor himself. All the rest is just “digital makeup.” To many animators (and their friends and admirers), this term “digital makeup” is practically an insult. What animators do is far more involved than “touching up” the captured image.

How can people look at the same footage and see something so different? I guess we shouldn't be all that surprised. Everyone's familiar with the idea that background beliefs and prior experiences

influence what we see. Or is it that they influence what we

think

we see? Can these two things be kept straight? In my field, philosophy of science, it was once fashionable to draw a distinction between “seeing as” and just plain “seeing.” This discussion seems to pop up every time we start comparing the perceptions of people who hold radically different beliefs (especially before and after a major scientific revolution). For example, we can imagine two people in the seventeenth century watching the sun set. Person A has read Copernicus and Galileo, and “knows” that the Earth spins on its axis once a day and is just one of several planets orbiting the sun. Person B is a little out of touch, but “knows” the Earth is stationary and that the sun orbits it once a day. So A and B believe very different things. But here's the question: when A and B watch the sunset, do they see the same thing or do they see different things? Perhaps they do see the same thing (the sun on the horizon), but each sees it

as

something else (a stationary and an orbiting body, respectively). Likewise, when Dr. Zira and Dr. Honorius watch Taylor's gestures at trial, Zira sees an attempt to communicate, whereas Honorius sees an animal's mimicry. This makes it sound as if they see two different things, but perhaps they see the same thing (Taylor's gestures); each just sees it

as

an instance of something else (communication and mimicry, respectively).

It's tempting to say that two people with different beliefs may see the same thing and interpret it differently. Sometimes this is true. If I write out “tomatoes, trout, potatoes, Shout” on a piece of paper, two people may see the same thing (a list of words) and interpret it differently (a grocery list and a poem). But it seems that most cases of seeingâand perception in generalâare all-at-once processes. This almost must be true of everyday perception. Imagine if all of our perception involved taking in sensory input, followed by a separate process of interpretation. It's tough to operate in the real world in real time with that kind of two-step perceptual set-up. In a world governed by natural selection, I doubt the human race would have made it to this point.

Yet a one-step perceptual process leads to another worry. If what we already believe so strongly colors what we see, what point is there in even consulting the Serkis footage to resolve the dispute? We encounter a serious problem if we simply

accept that what we perceive depends on our prior beliefs. It seems that if we went too far in this direction, we would never be able to use observations to change our minds. We'd be sentenced to a life of dogmatically held beliefs.

Can we be trained to see things differently than we currently do? This would be a way out of the difficulty. I find optical illusions to be illuminating on this point. They can teach us an interesting lesson regarding the influence of belief on perception.

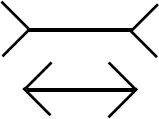

A famous optical illusion is the Müller-Lyer illusion. It involves two horizontal lines:

The top line looks longer than the bottom line, but in fact, they're the same length. If you don't believe me, measure them. After measuring, you should now believe that they are. But do they look it? No, the top line still looks longer. We still fall prey to the illusion despite our beliefs. In fact, as philosopher Jerry Fodor has pointed out in “Observation Reconsidered,” what we believe does

not

dictate what we see.

Great! So improvements to our knowledge don't dispel illusions. This is supposed to help us trust our perceptions? How can we have any hope of figuring out whom to credit for the emotional and aesthetic hold Caesar has on us: Serkis or Engel?

Here's the problem. Throughout this discussion we have been awash in false dichotomies: either our perceptions depend on our beliefs or they don't; either the viewer's emotional connection to Caesar is due to acting or to animation. In fact, we can determine (through measurement) that the two lines are the same length, and we can learn (through discussion, through having certain visual cues pointed out to us) how acting

and animation

both

contribute to the emotional and aesthetic effect of Caesar. Sit down and watch the video clips with a CG animator and an actor and you will start to pick up on what they are picking up on.