Poison (29 page)

Authors: Jon Wells

“He said that he can’t keep coming back here all the time,” she replied. “His house is in Canada and he wants to get this over with.”

Dhinsa asked if Dhillon had ever threatened to hurt Surinder if she told others about his multiple marriages.

“He said there would be a fight in the house,” she answered. “He has a short temper and I am afraid of him.”

Before they left, Dulla arrived—Manjit Singh Sidhu, Dhillon’s old friend and an officer with the Punjabi state police. He seemed to hover over them, saying little. Korol thought he looked like Ali Baba. It was not the last time Dulla appeared out of nowhere when the detectives were poking around Ludhiana. They returned to Tibba, retrieved photo negatives of Kushpreet’s wedding to Dhillon. As evening fell, they visited Parvesh’s brother, Seva. He was a generous, friendly man, a practicing Sikh who wore the turban, a symbol of his devotion. Once, a visitor asked him what it felt like to wear a turban, and Seva promptly removed the sacred head-wrapping and placed it on the guest’s head. He had his own business in Ludhiana, and there was still the family farm, a 25-acre property a few kilometers from their home. He missed his sister terribly.

“I am a God-fearing man,” he said. “I believe in my religion. But many times I’ve asked God, ‘Why did this happen?’ It is still in my head. Why?”

Seva insisted that Korol, Dhinsa, and Kundu join him in a toast to his late sister. He beckoned his son to open a new bottle of Aristocrat whisky, then splashed the golden liquid over the

ice in the glasses. They made a toast. And then another. Seva reveled in entertaining. It was past midnight now. Korol turned to Dhinsa.

ice in the glasses. They made a toast. And then another. Seva reveled in entertaining. It was past midnight now. Korol turned to Dhinsa.

“Kevin, let’s just grab a hotel room in town,” he said.

Dhinsa would have none of it.

“Warren, we just can’t. It’s deplorable here.”

Their driver took them all the way back to Chandigarh.

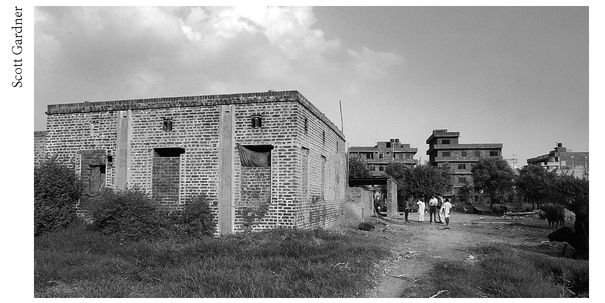

On May 8, they returned to Birk Barsal once more, this time to visit Dhillon’s farm, a small patch of green in the middle of the urban craziness. There was a barn, cattle, and workers.

The Dhillon family farm

“Do you know Dhillon?” Dhinsa asked one of the workers.

“Only to see him.”

“Are you familiar with

kuchila

?”

kuchila

?”

“No.”

They knocked again at Dhillon’s walk-up apartment. Dhillon’s nephew, Manminder, was home.

“What was Sukhwinder Dhillon’s reaction to the news of Kushpreet’s death?” Dhinsa asked.

“He cried when he heard,” Manminder said.

“Did you see tears, or did he just cry out loud?”

“There were tears.”

“How could a man be sad about a death and then marry another woman very shortly after?” Dhinsa continued.

“That I don’t know. Only he would know that.”

The detectives had not been at the apartment for long when big Dulla arrived. This time he spoke with the detectives in broken English. They learned that Dulla had earned his reputation some 13 years earlier when the Indian government sent the army to quell a bloody uprising by Sikh nationalists in Amritsar. Dulla had fought for the army and was repaid for his service with a rapid rise through police ranks.

“So how many people did you kill up there?” Korol asked.

“Twenty-five.”

Dhinsa nudged Korol. He noticed the bump under Dulla’s shirt, the revolver.

“Mind if I take a look?” Korol said. He reached over, lifted the tail of Dulla’s shirt, and slid out the small revolver. He examined it and emptied out the ammunition. Then he handed it back. Dulla said nothing. Maybe his appearance and reputation were exaggerated. Or perhaps he feared a reprisal from the CBI man, Subhash Kundu.

“Did you attend the wedding of Sukhwinder Dhillon and Sukhwinder Kaur?” Dhinsa asked.

“No. I didn’t have time,” replied Dulla.

“We have a signed document that says you were at the wedding.”

Dulla looked at the officers.

“I signed it,” he admitted.

“You just told us you didn’t go to the wedding.”

“I went to the wedding.”

Kundu interjected. “What is your duty as a police officer?” he asked.

“Wherever the criminal is, catch him.”

“As a police officer, didn’t you think something was suspicious with all these marriages involving Dhillon?”

“He used to say, ‘My wife is dead, I need a mother for my children.’”

Dulla stood to leave. Korol lifted his camera. Dulla held up his hand. There would be no photos.

Back on the road, they drove two hours out of Ludhiana, past straw huts that were used to store cow dung for fuel, through dusty markets and along creeks where cows gathered to cool off. They arrived in Dhandra, home to Dhillon’s fourth wife, Sukhwinder Kaur. The village name wasn’t even on a map. It was just there, had always been there. Along the tight cobblestone streets, cars turned in their side mirrors to avoid scraping the walls of buildings on either side.

“How the hell do you find these places?” Korol said. Kundu grinned.

In a narrow alleyway, they stopped, got out of the car, the heat striking like a chorus of sun lamps, no breeze, taking their breath away. Their driver parked in a sliver of shade, shut off the engine, locked the doors, pulled out a cloth to wipe his face and waited. A woman appeared in a doorway and beckoned them inside through a dark hallway, then into a dimly lit main bedroom and living area. A fan labored, light streamed through an arched window revealing pale green walls festooned with prints of Sikh gurus. Like other homes they visited, this one was colorful and inviting inside, a stark contrast to the nondescript exterior.

Sukhwinder Kaur was plump and had an oval, expressive face. She seemed outgoing, made eye contact with the men and always seemed ready to break into a smile. Kundu sat beside her on the large bed while Korol and Dhinsa went to the couch. Korol opened his laptop and began typing.

“What did Dhillon tell you about his first wife, Parvesh?” Dhinsa asked.

“Dhillon told me that Parvesh had been fasting before she died,” she said. “He said she slipped down the stairs and fell, then died several days later.”

“Are you aware,” Dhinsa asked, “of the investigation in Canada into the deaths of Parvesh Dhillon and Ranjit Khela, and that Sukhwinder Dhillon is the prime suspect?”

“He told me that no one could kill their own wife and their best friend.”

At 28 she was both older and better educated than either Sarabjit or Kushpreet—she had gone to a women’s college in

Ludhiana for three years—and carried herself in a more assertive manner. She’s a feisty woman, thought Korol. Kundu did not consider Sukhwinder Kaur a victim. He believed she was well aware that, when she married Dhillon, he had committed bigamy. Perhaps she thought the last two marriages had been annulled in some way. But she knew about them. She simply yearned to get to Canada. She handed Korol a copy of a Canadian immigration application that showed Dhillon was sponsoring her. She believed she still deserved the opportunity to get to Canada. Was there still hope? The Canadian police were here, perhaps there would be a trial, perhaps they would take witnesses like Sukhwinder Kaur to Canada to tell their story.

Ludhiana for three years—and carried herself in a more assertive manner. She’s a feisty woman, thought Korol. Kundu did not consider Sukhwinder Kaur a victim. He believed she was well aware that, when she married Dhillon, he had committed bigamy. Perhaps she thought the last two marriages had been annulled in some way. But she knew about them. She simply yearned to get to Canada. She handed Korol a copy of a Canadian immigration application that showed Dhillon was sponsoring her. She believed she still deserved the opportunity to get to Canada. Was there still hope? The Canadian police were here, perhaps there would be a trial, perhaps they would take witnesses like Sukhwinder Kaur to Canada to tell their story.

CHAPTER 16

“DHINSA IS DEAD”

The Hamilton detectives and the Indian CBI inspector became close friends. Near the end of their stay, Kundu showed the Canadians a place in Chandigarh to buy tailored suits, and the detectives left their measurements with the tailor for future orders. On their last night together, they ate dinner in the Piccadilly Hotel’s Empress Room. For Kundu, reputation was everything. He led a comfortable life in Chandigarh. But his apartment and his motorcycle were merely material possessions. His goal, ultimately, by the grace of God, was passage into heaven. He would actually pose the question directly.

“What do you think of me? What do you think of Inspector Kundu? What do you feel, in your heart?”

At dinner, Korol suggested they invite the man who had been their driver, a young man they called Bubaloo, to join them. Kundu closed his eyes, pursed his lips, and shook his head, not bobbing it in the Indian way of saying yes, but in the negative. It wasn’t done. Drivers in India drive. They are proud of their job, it is what they do. They associate with other drivers.

“The driver? He can’t come in here.”

It hit Korol—here they were, two police officers, but culturally worlds apart. Status is part of India’s fabric. That could be said for any society, but in India, with its caste system, status is defined at birth and there is no escaping it. Europeans joke that, in the United States, the customer calls the waiter “sir.” Not in India. Kundu, a man with a generous spirit, would hold up his hand to a waiter, wave him over, barely looking at him. The waiter was not offended in the least. It was his role.

Korol could never get his head around the caste system. Sikhs had rejected it, too, centuries ago. But here was the caste system alive and well in Punjab, he thought. In the West, status matters, but Korol himself was proof that life can be what you make it. Raised by working-class parents, a family with no university graduates, he climbed the career ladder and educated himself at a top university. In their trips to the villages, after parking, Bubaloo would scramble out of the car and hold the door open for Korol.

“Get outta here—don’t be opening doors for me,” Korol playfully growled.

At the end of the trip Bubaloo asked Korol for his autograph. Korol chuckled. “No, Bubaloo, I won’t do that,” he said, as though the rejection would awaken Bubaloo to the notion that he, a driver, was every bit as important as a big police officer from Canada. But when Bubaloo became upset at the slight, Korol relented, signed a scrap of paper, and gave it to him.

In the Empress Room with Dhinsa and Kundu, Korol wasn’t about to take on the caste system on his own and insist Bubaloo eat with them. But he wasn’t giving up, either.

“Subhash, tell the waiter to get some food to the kid.” The waiter, a puzzled look on his face, carried a plate of food out the door into the parking lot to Bubaloo, courtesy of Detective Warren Korol.

The next day Korol and Dhinsa said goodbye to their friend Kundu and returned to New Delhi by airbus from Chandigarh airport. No more train rides. On May 13 they met again with RCMP liaison officer Pierre Carrier at the Canadian High Commission on Shanti Path in New Delhi.

“After I return to Hamilton I’m going to send a letter, through you, to the Indian authorities to see where they stand on exhuming the twins,” Korol said.

Carrier, from Chicoutimi, Quebec, was impressed. During his three years in New Delhi, he had frequently served as a go-between with Canadian police and Indian authorities, but had never heard such a request. Later, he would inch his way through the Indian penal code, a document that dates back to 1858. There was not one reference to exhumations.

Korol pulled out a photocopy of the Canadian immigration application that showed Dhillon falsely claiming Sukhwinder Kaur as his lawful wife.

Other books

Those Who Leave and Those Who Stay by Elena Ferrante

Starfire (Erotic Romance) (Peaches Monroe) by Strong, Mimi

A Permanent Member of the Family by Russell Banks

1972 by Morgan Llywelyn

Program 12 by Nicole Sobon

Secrets (A Standalone Novel) (A Suspense Romance) by Adams, Claire

Love, Hypothetically[Theta Alpha Gamma 02 ] by Anne Tenino

Brando by Hawkins, J.D.

Maybe by John Locke

Play on by Kyra Lennon