Poison (25 page)

Authors: Jon Wells

On March 24 the search of Dhillon’s house ended and police packed up their hulking command vehicle and left. Now the media were deep into the story. A

Hamilton Spectator

reporter named Jim Holt spoke to Dhillon at his house. “It’s terrible,” Dhillon said. “My English is bad. Speak to my lawyer.” Dhillon stepped into the house, then re-emerged with his brother, Sukhbir.

Hamilton Spectator

reporter named Jim Holt spoke to Dhillon at his house. “It’s terrible,” Dhillon said. “My English is bad. Speak to my lawyer.” Dhillon stepped into the house, then re-emerged with his brother, Sukhbir.

“Of course we are angry, what do you think?” Sukhbir said. “Who wouldn’t be angry if police force them from their home? It’s all just gossip, 100 percent gossip.”

Ben Chin, a TV reporter from Toronto, rolled into town. He spoke to Korol. “Do you know where I could find Mr. Dhillon’s lawyer, Richard Startek?” he asked.

“Mr. Startek does a lot of family court matters,” Korol replied. “You might find him in Unified Family Court.” Chin said he knew there were other deaths in India being investigated. Korol asked Chin if he knew anything about strychnine.

“No.”

“You might want to familiarize yourself with it. And by the way, have you asked Dhillon where he was when the people in India died?”

“No.”

“You might find the answers interesting.”

Korol planted a couple more questions in Chin’s head. The reporter might also ask Dhillon if his first wife had used homeopathic medicine. Warren Korol worked with the media—and

worked

the media. Through the reporter he saw an opportunity for Dhillon to lie and hang himself on the record. He was sure Dhillon wouldn’t disappoint.

worked

the media. Through the reporter he saw an opportunity for Dhillon to lie and hang himself on the record. He was sure Dhillon wouldn’t disappoint.

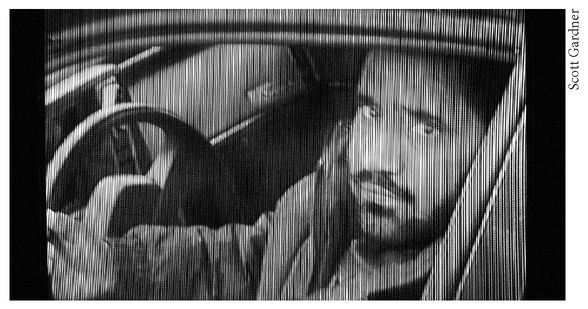

Chin, his straight black hair flowing to the shoulders of his white trench coat, showed up near Dhillon’s home two days later and gave him a taste of hard-core TV news on the fly. He cornered Dhillon in his car, parked on a neighborhood street. He didn’t let his subject go, led him with his questions, offered empathy.

“Did the police tell you they were going to come?” Chin asked.

“No, I don’t understand English so well. Please leave me alone,” Dhillon said, speaking quickly.

“I just want to tell your side of the story,” Chin replied earnestly. “Do you think the police are picking on you?”

Dhillon nodded.

“You are an innocent man,” Chin said. “You open your door to police. They can check your house all they want, they won’t find anything, right?”

Video from a TV reporter’s interview with Dhillon

“No, no, nothing.”

“They are saying it’s poison that killed your wife.”

“No, no poison. I am 100 per cent clear, no problem. Police investigate, no problem.”

“What about the people who are dead in India?”

“She’s not my wife.”

“How many wives have you had?”

“Please, no more, I’m upset. I was divorced, that’s it.”

“To set the record straight,” Chin continued, “you are a victim here. You’ve done nothing wrong.”

“I’m 100 per cent clear.”

“If anything, you’ve had very bad luck, people dying.”

“Right. He was a son to me. Please, talk to my lawyer.”

“Thank you very much.”

“I’m 100 per cent clear. Clear, clear, clear, clear.”

“Somebody in your community is trying to make you look bad.”

“Yes. Some people very nice, some people bad. Making stuff up. I’m 100 per cent clear in my heart.”

“And what about the twins? Are they dead?”

“No—I never saw them. Never touched them.”

Korol and Dhinsa met with Brent Bentham on April 24 to discuss the points to be covered in India. They needed to find out every detail about the deaths there from witnesses, obtain documents from government offices to confirm births, marriages, and deaths, determine whether doctors were called for all of the deaths and why autopsies were not performed. They also had to ask witnesses to the three deaths exactly what symptoms the victims had exhibited. And they needed to go shopping for strychnine. On April 28, a jet took off from Toronto’s Pearson Airport with the two detectives on board.

Chandigarh, India

May 1, 1997

May 1, 1997

Each morning, CBI Inspector Subhash Kundu woke by 6:30 a.m. His wife, Jogi, whom he had married as arranged by his Hindu parents, made him breakfast, usually toast or an omelet, perhaps

bratha

—a type of bread—with yogurt. Then he reported to his office at the Central Bureau of Investigation building in Chandigarh, the Punjabi capital. But there were other times when the CBI inspector rose much earlier, answering a phone call in the middle of the night. A suspect in a corruption case to be questioned.

Kundu should pay him a visit. He’d dress, load his firearm, and drive his cream-colored Pajha motorcycle through the dark streets and hot air, past rows of towering eucalyptus trees shedding their fine bark, the trunks like polished bone in the moonlight. At the apartment, a rap on the door and the suspect was invited to join Kundu back at the CBI station. Then the interrogation in a gray windowless concrete room with a rattling fan.

bratha

—a type of bread—with yogurt. Then he reported to his office at the Central Bureau of Investigation building in Chandigarh, the Punjabi capital. But there were other times when the CBI inspector rose much earlier, answering a phone call in the middle of the night. A suspect in a corruption case to be questioned.

Kundu should pay him a visit. He’d dress, load his firearm, and drive his cream-colored Pajha motorcycle through the dark streets and hot air, past rows of towering eucalyptus trees shedding their fine bark, the trunks like polished bone in the moonlight. At the apartment, a rap on the door and the suspect was invited to join Kundu back at the CBI station. Then the interrogation in a gray windowless concrete room with a rattling fan.

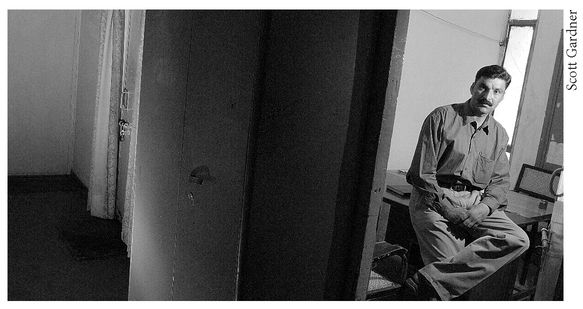

Inspector Subhash Kundu in his office in Chandigarh

On the morning of May 1, 28-year-old Subhash Kundu woke early for a different reason. It was one of those mornings when he needed no alarm. The Canadian detectives were arriving today at the train station. CBI officials occasionally cooperated with a Canadian RCMP liaison in New Delhi on immigration matters. But it was unheard of for a CBI man to work hand in hand with Canadian police officers on a murder investigation.

India’s CBI has a role comparable to that of the RCMP or FBI. Its officers enjoy a measure of respect as a result. That’s quite different from India’s regular uniformed police, who are infamous for petty corruption. There is a saying that, in India, a police officer can turn a suicide into a murder, or a murder into a suicide, for the right price. Even after a car accident, witnesses and victims are reluctant to phone police for fear they’ll end up having to pay for their services on the spot. As with all things that shock foreigners about India, the root cause is complicated. Uniformed local police in India are paid poorly for difficult and often grisly work.

By the time Korol and Dhinsa arrived in India, Kundu had already completed much of the leg work. All that remained was for the Canadians to confirm what he had discovered. Kundu had been on the road gathering information for several weeks after being assigned to the Dhillon case, interviewing family members of victims.

Kundu knew well the fleeting nature of life in India. He had a dark sense of humor about it. Off duty, over a couple of beers and cigarets, Kundu observed that in the event of a nuclear war between India and Pakistan, Pakistan could strike first and kill more than a million Indians, but India would win the war. And the million dead? “India is overpopulated anyway,” he said, “so that wouldn’t be such a bad thing.” Then Subhash Kundu waited, his face deadpan, for the reaction of his audience before he grinned and the dark eyes danced.

Still, even Kundu was shocked by the trail Dhillon left. He thought the man was a bastard. No matter what happened, he believed Dhillon would be judged and found guilty in a higher court some day. You can escape human justice. But not God’s.

Kundu drove to the CBI office, the flesh-toned building in Sector 30-A, on Thursday morning. Two guards with rifles stood out front in their tan uniforms. Kundu, wearing his usual dress shirt and pants, strode past the CBI logo in the lobby, up the four flights of steps, the air still and stale, then down a darkened, pistachio-green hallway. He unlocked the padlock on his office door. Two desks faced each other. A tattered ceiling fan shook as it rotated thanks to the crack in its base. The walls in the dreary, windowless room were ivory-colored concrete marked with splotches of greenish blue that looked like chunks of torn rain clouds. It was a pitiless room, no character or warmth, not one photo, no medals or diplomas, no certificate attesting to the fact that Subhash Kundu was one of India’s elite, a man who scored high enough on the Indian Police Service test to merit immediate appointment as Inspector.

Kundu was born in the pitched heat of summer in 1968, in a village called Kinals in the province of Haryana, south of Punjab. His father, Birmati, served in the Indian army, so the family moved

frequently. In 1990 he took the police exam to obtain a position in the CBI. He was appointed a sub-inspector the following year. He was just 23. He was posted in New Delhi for a year, then transferred for the next four years to remote areas in Kashmir—the flashpoint between nuclear rivals Pakistan and India. In 1996 he was transferred to Chandigarh. He lived a good life with his wife and two children, Shilpa and Abhishek. They had their own apartment in the most orderly and clean major city in northern India, which sits two hours from the Himalayan foothills. They took day trips to mountainous Simla, rode the cable car at Parwanoo, lunched overlooking the ridges and green valleys.

frequently. In 1990 he took the police exam to obtain a position in the CBI. He was appointed a sub-inspector the following year. He was just 23. He was posted in New Delhi for a year, then transferred for the next four years to remote areas in Kashmir—the flashpoint between nuclear rivals Pakistan and India. In 1996 he was transferred to Chandigarh. He lived a good life with his wife and two children, Shilpa and Abhishek. They had their own apartment in the most orderly and clean major city in northern India, which sits two hours from the Himalayan foothills. They took day trips to mountainous Simla, rode the cable car at Parwanoo, lunched overlooking the ridges and green valleys.

He left his office, walked down the hall to the weapons room, wrapped his hand around the black plastic grip of a revolver, and returned to the office. The gun was a vestige of India’s colonial days. The British had granted India independence in 1947 but their influence lingered in many ways, from bits of English that became part of the Hindi and Punjabi languages to steering wheels on the right side of cars, to the Webley & Scott handguns still used by police. The Mark IV .38-caliber revolver was a break-top—it snapped open for loading. It was now considered an antique of sorts, but was still reliable and a man-stopper when required. Kundu loaded the gun with six round-nosed bullets, then wedged it into the belt holster in the back of his pants. He usually kept his gun at work and wore it only when necessary. It was uncomfortable, for one thing, but today it felt right.

The Dhillon assignment was potentially dangerous. Dhillon and his friends would know the police were on the case. They would not be pleased. It wouldn’t take much for a friend or ally of Dhillon to catch the detectives in a remote village or even in a crowded market. The Canadians would not be permitted to carry firearms in India. So he, Subhash Kundu, would protect them. He couldn’t rely on local police in the villages, among whom Dhillon had friends. Korol and Dhinsa wouldn’t know Kundu was armed. That wasn’t necessary.

Other books

Murder at the Blue Plate Café (A Blue Plate Café Mystery) by Alter, Judy

Amy's Touch by Lynne Wilding

My Happy Days in Hollywood by Garry Marshall

Autumn Getaway (Seasons of Love) by Gracen, Jennifer

Flamingo Fugitive (Supernatural Bounty Hunters 5) by E A Price

I Surrender by Monica James

Snatchers 2: The Dead Don't Sleep by Whittington, Shaun

Can't Stop Loving You by Peggy Webb

Road Dogs (2009)( ) by Leonard, Elmore - Jack Foley 02

Stone Kiss by Faye Kellerman