Project Sweet Life

Read Project Sweet Life Online

Authors: Brent Hartinger

For Michael Jensen

For making my own life very sweet indeed

The Idea

The Junk-Free No-Garage Garage Sale

Robberies in Plain Sight

Counting Beans (And Not Spilling Them)

The Pirates’ Plunder

The Perfect Crime

A Deal with the Devils

Sunk

The Very Last Chance

The Sweet Life

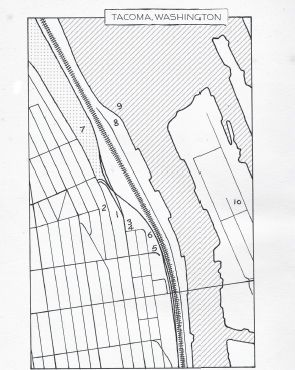

- Old City Hall

- Spanish Steps

- Meconi’s Pub

- Olympus Hotel

- Totem Pole

- Fireman’s Park

- Greenbelt

- Thea Foss Park

- Dive Site

- Tideflats

“Dave,” my dad said at dinner, “it’s time you got yourself a summer job.”

“What?” I said. The only reason I didn’t choke on my spaghetti meat loaf is because he couldn’t have said what I’d thought he said. True, it was the night before the first day of summer vacation. But I was only fifteen years old. For most kids, fifteen is the year of the optional summer job: You

can

get one if you really want one, but it isn’t

required

. And I really, really didn’t want one.

My dad is a real man’s man, a straight-backed guy with a buzz cut and a deep rumble of a voice. For him,

things are always very black-and-white.

“It’s definitely time you got a job,” he repeated, gnawing on the meat loaf like a grizzly bear. “Get out in the world, meet some up-and-comers. After all, you are who you surround yourself with.” This last part was something my dad was always saying—something about birds of a feather and all that.

But even now I didn’t choke on my food, because I was still certain he was kidding about my getting a job. Even if in the weirdest reaches of some wild, alternate universe where my father suddenly

did

think I should get a job the summer of my fifteenth year, even

he

wasn’t so cruel as to bring it up on the night before the start of my vacation.

“Yeah, right,” I said, taking another bite. “How about superspy? Between shadowing drug runners in South American nightclubs and cracking safes in Monaco casinos, I’ll still be able to sleep in.”

My dad sighed. “Dave, Dave, Dave,” he said. This was his standard expression of disappointment in me. “It’s high time you stop relying on your mother and me for money. This is the summer you start paying your own way in life. No more allowance for you. This is the

summer you get a job.”

Now

I choked on my spaghetti meat loaf! Not only was my dad forcing me to get a summer job, he was also stopping my allowance?

“But, Dad!” I said. “I’m only fifteen!”

“What does that have to do with anything?” he said.

I tried to explain how fifteen was the summer of the optional summer job.

“Says who?” my dad said.

“Says everyone!” I said. “That’s just the way it works! It’s probably in the Bible somewhere. Or maybe the U.S. Constitution.”

“I don’t think so.”

I looked at my mom, but she was blankly sipping her raspberry-mango juice blend. It was clear I wasn’t going to get any help from her.

“Well, it

should

be,” I said.

My dad just kept wolfing down the spaghetti meat loaf.

Before I go too far on this, I need to explain how I feel about work in general and summer jobs in particular. I don’t want anyone thinking I am some sort of

anti-American or anti-work deadbeat.

I believe in work. Without it, civilization collapses: Buildings don’t get built, pipes stay clogged, breath mints would go unstocked. Personally, I

like

it when I use the public restroom and find that the toilet paper dispenser has been refilled.

I also believe in the idea that the harder you work, the more you should get paid. You’re too tired to work? Well, then I guess you’re also too tired to eat.

Work is important. I get that.

That said, I

do

work. Hard. At school, for ten months every year. Unlike a lot of people my age, I take school very seriously. My eighth-grade report on Bolivia was as comprehensive as anything in

The New York Times Almanac

. One of my freshman English essays was almost

frighteningly

insightful into the significance of those worn steps at the school in

A Separate Peace

.

And, yes, I certainly understand that some people, even some fifteen-year-olds,

need

to work. They’re saving for college, or they have to help pay bills around the house. For them, a summer job at fifteen isn’t optional. But my dad makes a good living as a land surveyor. He wears silk

ties! And my mom is stay-at-home. We aren’t poor.

The adults won’t tell you this, but I absolutely knew it in my bones to be true: Once you take that first summer job, once you start working, you’re then expected to

keep

working. For the rest of your life! Once you start, you can’t stop, ever—not until you retire or you die.

Sure, I knew I’d have to take a job next summer. But now, I had two uninterrupted months of absolute freedom ahead of me—two summer months of living life completely on my own terms. I knew they were probably my last two months of freedom for the next fifty years.

The point is, dad or no dad, I was going to be taking a job the summer of my fifteenth year over my dead body.

“My dad is making me get a summer job,” said my best friend Victor Medina later that night. “

And

he’s stopping my allowance.”

“You’re

kidding

!” said my other best friend, Curtis Snow. “So is mine!”

We’d met in the old bomb shelter in Curtis’s backyard after dinner. The shelter had been dug in the early 1960s

but had been abandoned until Curtis had talked his parents into letting him, Victor, and me turn it into our own personal hideaway. And what a hideaway! We’d brought in carpet, a really plush couch, and these giant oversize floor pillows. We’d also wired in electricity from the house, which let us add things like a little refrigerator, a movie-style popcorn popper, even a flat-screen television and game system—all top-notch stuff that we’d picked up at bargain prices at garage sales and on eBay. Even Curtis’s parents didn’t know about everything we had hoarded in there, mostly because we’d long since installed a thick lock on the door, designed to be so secure that it would even keep out panicky neighbors clawing to get inside after the launch of a nuclear missile, and no one knew the combination except us.

“Wait,” I said. “This is too weird. My dad is making

me

get a summer job too.”

We stared at one another, trying to make sense of this amazing coincidence. The air smelled like raspberry syrup from our Sno-Kone machine.

Curtis, Victor, and I have been friends for years. Curtis is the Big Picture Guy, outgoing and impulsive, a great talker and an even better liar. He likes stories of

all kinds, and life is never dull when he’s around. He’s blond, athletic, and pretty good-looking, with rosy cheeks and tousled hair. But his looks are deceptive, like those tropical clown fish that are bright and colorful and innocent-looking but which really exist just to lure other fish into the poisonous tentacles of a sea anemone. Still, the fact that Curtis looks like a choirboy is why people don’t strangle him for lying, which he usually shrugs off as “shading the truth.” On the downside, well, along with the lies, he talks a lot.

Victor is the opposite of Curtis. He isn’t blond or athletic. He’s a small guy, Hispanic, with glasses. He’s well-groomed and combs his hair in an eerily even part. I sometimes think of him as a character in some black-and-white movie—not the lead but the sarcastic best friend who mumbles witty asides in the background. Victor is more practical than Curtis, and more detail-oriented, which may be why he likes science and computers. He’s a watcher, not a doer. On the downside, he can be prickly and panics easily.

As for me, Dave, I am kind of like a mix between Victor and Curtis, and not just because I have a medium build and brown hair with an uneven part. It’s the way

I act, too, always torn between dreaming big and being cautious. What’s my downside? I don’t really think I have one. Then again, I don’t have to be friends with me.

But if Curtis, Victor, and I were different in some ways, we were all in complete agreement when it came to summer jobs for fifteen-year-olds.

“Our dads talked,” Victor said. “It’s the only explanation. Saint Craptilicus,” he added with a mutter. Victor’s family is old-school Catholic. He says that since there are already so many saints in the church, it doesn’t matter if he adds a few more. So now, whenever the situation calls for it, he invokes new, custom-made saints.

He was also right about our dads. They work together at the county surveyors’ office; their being friends is how the three of us met in the first place. They eat lunch together, go out for beer and darts after work every Tuesday, and sometimes play golf on the weekends too. It couldn’t be a coincidence that all three had suddenly decided their sons needed to get summer jobs. It had probably happened on the golf course that very afternoon.

“I wonder whose idea it was,” I said.

“My dad,” Curtis said.

“My dad,” Victor said.

I, of course, was positive it was

my

dad who had brought it up. I could almost hear the conversation:

You know, Ray, ever notice how

easy

our sons have it?

They sure do, Brian! A lot easier than we had it when

we

were their age! Don’t they, Andy?

Absolutely right! And it’s high time they pull their own weight!

Build some character!

Learn the way the world

really

works!

“First they say we’re just kids,” Victor said. “That we can’t surf the internet without filters or buy this video game or go to that movie. But then they want to make us take on all the responsibilities of an adult? They can’t give us the responsibilities without the privileges! That’s not fair.”

“Amen!” Curtis said. “Sing it, brother! I mean, if being a kid means anything at all, it means summer vacation. And this is our last ‘true’ summer vacation—the last one where we don’t

have

to work. Our last taste of true freedom!”

Needless to say, there’s a reason why Curtis and Victor are my best friends.

“We had

plans

,” Curtis went on. “We were going spelunking with my sister and her boyfriend. We were going to go scuba diving.” Sure enough, we’d all gotten our dive permits earlier that year.

“And what about bike rides,” I said, “and swimming at the pool and hiking in the woods?”

“Who knows?” Victor said. “We might have even hung out at the mall.”

“The point is,” Curtis said, “this summer was going to be the sweet life, and now it’s not.”

“But what can we do?” I said. “I mean, they’re our

dads

.”

Curtis thought for a second. Then, very quietly, he said, “We could lie. Say that we’ve taken summer jobs when we really haven’t.”

The walls of the bomb shelter were thick enough to muffle the screams of neighbors dying of radiation poisoning, but Curtis had whispered anyway. I knew why. What he was suggesting—lying to our parents—was A Very Big Deal.

Victor and I didn’t say anything. The soft-serve ice-cream machine hummed. The watercooler gurgled.

Finally, I said, “That won’t work. My dad’s going to want to see the money I earn.”

“Besides,” Victor said, “I don’t want to lie to my parents. About little things, sure. But this is a big thing.”

“Yeah,” Curtis said reluctantly.

We stared at the walls, at our framed posters for

Indiana Jones

and

Pirates of the Caribbean

—movies about adventures that we definitely wouldn’t be having this summer. Remember when I said Curtis was like a clown fish, luring people into things they later regretted? The suggestion that we should lie to our parents—that was the poisonous sea anemone he was trying to lure me and Victor into. I knew it, and Victor knew it. So part of me was relieved that Victor and I had so quickly put the kibosh on Curtis’s idea. That said, I couldn’t stop thinking about how unfair it was that my dad was making me get a summer job. So another part of me wanted Curtis to keep talking.

And Curtis did. “Wait a minute,” he said. “Our dads just said summer jobs, right? They didn’t say

what

summer jobs.”

“Yeah,” Victor said. “So?”

“So what if we found some way to make all the money we

would have made

at our summer jobs? Like a onetime job with a big payoff? After all, it’s about the money, not the actual work, right?”

“No,” I said. “For my dad, I think it totally

is

about the actual work. And the people I supposedly meet along the way.”

“Mine too,” Victor said. “My dad says work builds character.”

“Says them,” Curtis said. “But if that’s what our dads-slash-slavemasters are saying, then that’s just stupid. It’s already not fair we’re being forced to make money we don’t need. But it’s

really

not fair if the only way we can make that money is through some dreary minimum-wage job. What about the creativity and smarts that we’d need to pull it off another way? Wouldn’t that build character too? Shouldn’t we get credit for

that

?”

“He has a point,” I said to Victor. “How much money are we talking, anyway?”

“Well, figure six-fifty an hour for forty hours a week.” Victor calculated. “That’s two hundred and sixty dollars. And there are—what? Ten weeks from now until

Labor Day? But figure it takes at least a week to find a job. So two hundred and sixty dollars times nine weeks? That’s about twenty-three hundred dollars we’d need to cover the whole summer.”

“Times the three of us,” I said. “So about seven thousand dollars.”

“That’s

it

?” Curtis said. “All we need is seven thousand dollars and we can take the whole summer off?”

“What do you have in mind?” I said. “Robbing a bank?”

“We don’t need to rob a bank. We can get seven thousand dollars

easy

. First, how much money do we have right now?”