Real Food (20 page)

Authors: Nina Planck

Scientists are just beginning to uncover how extracted vitamins are imperfect substitutes for foods. Whether vitamin E supplements

are helpful, for example, has been hotly debated. Why are the studies equivocal? Here's one hypothesis: the vitamin E in supplements

is usually alpha-tocopherol, but the vitamin E "complex," as the natural vitamin E in foods like avocados is known, contains

at least seven other agents, including beta-, delta-, and gamma-tocopherol. The other agents may be equally or more important.

In a similar fashion, the vitamin C in most pills is merely ascorbic acid, but the C complex includes the flavonoid rutin

and the enzyme tyrosinase. Without tyrosinase, ascorbic acid doesn't cure fever. Thus, maybe beta-carotene supplements didn't

help smokers in that well-publicized study because isolated beta-carotene does not equal a carrot.

Eating fruits and vegetables is still the best preventive measure. They simply don't know how to put all the benefits of foods

like beets and broccoli and berries into a pill.

Some Surprising Facts About Fats

THE BAD FOR YOU COOKBOOK,

published in 1992, in the midst of the frenzy for "light" cooking, extolled lard, eggs, butter, and cream— for pleasure if

not health. Chris Maynard and Bill Scheller presented their favorite recipes for shirred eggs, lard pie crust, and trout with

bacon with unguarded enthusiasm— and this disclaimer: "As for heart attacks . . . we are not going to make any hard-and-fast

recommendations here because we are not doctors and— far more important— we are not lawyers."

How little has changed since then! Many Americans are still terrified of eating fats and feel guilty when they do. Monounsaturated

olive oil makes the official list of "good" fats, yet few will defend saturated fats. Traditional fats are certainly more

fashionable recently. The television chef and restaurateur Mario Batali made a splash putting

lardo

(cured fatback) on his menus, and food writer Corby Kummer praised lard in the op-ed pages of the

New York Times.

"Here's my prediction," wrote the trend-spotting columnist Simon Doonan in the

New York Observer,

after he saw Kummer's piece on lard. "This trend is not only going to catch on, it's going to sweep the nation."

Well, I hope so. Lard may be in vogue, but hardly anyone knows that lard is good for you. When I began to read about fats

with an open mind, I learned some curious things. Consider this: lard and bone marrow are rich in monounsaturated fat, the

kind that lowers LDL and leaves HDL alone. Stearic and palmitic acid, both saturated fats, have either a neutral or beneficial

effect on cholesterol. Saturated coconut oil fights viruses and raises HDL. Butter is an important source of vitamins A and

D and contains saturated butyric acid, which fights cancer. As for the vaunted polyunsaturated vegetable oils, we eat far

too many. Refined corn, safflower, and sunflower oil lower HDL and contribute to cancer.

Back when I took the warnings about saturated fats to heart, I cooked everything— from roast chicken to salmon, mashed potatoes

to polenta— with olive oil. After I did a little homework on fats, life in the kitchen got more interesting. What fun to rediscover—

and in some cases learn for the first time— how to cook with traditional fats like butter and lard. Now my kitchen is stocked

with local butter, lard, duck fat, and beef fat, as well as exotic oils of coconut and pumpkin seeds.

Fats have many roles in cooking. Perhaps most important, they carry and disperse flavor throughout foods. Olive oil takes

up the flavor of chili, garlic, or lemon and spreads it through the dish. Chicken breast has less flavor than dark thigh meat

because it contains less fat, and modern commercial pigs, bred to be lean, make for dry and flavorless pork compared with

traditional breeds.

The Bad for You Cookbook

authors want to know: "How did the fat get bred out of hogs to the point where you'd have to render three counties in Iowa

to get a pound of lard?"

Fats add and retain moisture (in roasting, for example), and they keep food from sticking in frying and baking. Bakers use

solid fats like butter, lard, and coconut oil to create a flaky, crumbly texture. Finally, and perhaps most mysteriously,

fats contribute the inimitable quality known as "mouth feel"— think of creamy butter, silky serrano ham, or crispy skin on

roast chicken. The desire for the

feel

of fat in food is universal. As anyone who has tried fat-free versions of real food knows, it has not been easy for food scientists

to mimic the delectable feel of fat without real fat.

Fats, in other words, are delicious. But they are also necessary for health. Fats in the omega family are called

essential

because the body cannot make them; we must get them from foods. The brain relies on omega-3 fats; deficiency causes depression.

Without fats, the body cannot absorb the fat-soluble vitamins A, D, E, and K. Fats are key to many other functions, including

building cell walls, immunity, and assimilation of minerals like calcium.

Digestion is impossible without fats. The cell membrane (also made of fats) controls the muscles of the gastrointestinal tract.

Fats stimulate the secretion of bile acids, which are essential for digestion. The vital role of fat in digestion is illustrated

by an obscure condition called

rabbit starvation,

caused by a diet exclusively of lean protein. The term comes from Arctic explorers forced to live on lean winter game for

months, and the symptoms are lethargy, nausea, diarrhea, weight loss, and eventually death. Without fat, digestion literally

fails and you starve— even if you're eating plenty.

Granted, this form of malnutrition is not likely to threaten many Americans. Fat is cheap and ubiquitous— or at least industrial

fats are. Today, overeating low-quality food is more often the cause of poor nutrition than starvation. So how much fat is

healthy? I don't count fat grams or the percentage of calories from fat and don't recommend it. My approach is simple: I eat

a variety of traditional fats and oils, and I balance rich foods with lighter ones.

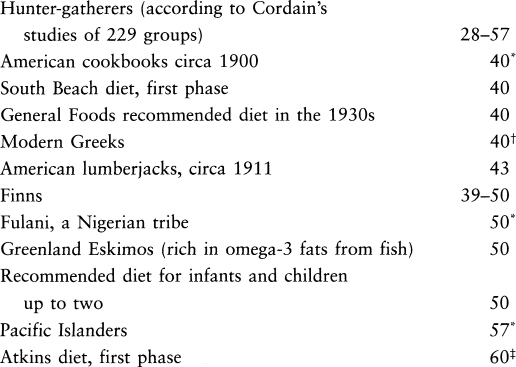

However, if you would like to know how much fat people eat and how much fat experts think we should eat, here are a few numbers.

Deriving less than 20 percent of calories from fat is regarded as a low-fat diet, 30 to 40 percent moderate, and 60 percent

high-fat. The extreme low-fat diet is recent, hard to follow, and nutritionally dubious. In 2006, the prestigious Women's

Health Initiative trial found that low-fat diets did not prevent weight gain, heart disease, stroke, or cancer.

1

The women on the "low-fat" diet were instructed to limit fat to 20 percent of calories, but that proved impossible (or perhaps

merely unpalatable). These unfortunate women, who gamely ate salads without olive oil for eight years with nothing to show

for it, consumed about 29 percent of their calories from fat. That's roughly what that U.S. government recommends. The lucky

women who were allowed to eat whatever they wanted (researchers call that

ad libitum,

a term I love) ate 37 percent fat, which happens to be typical of most human diets. Very high-fat diets are probably inappropriate

for those of us who work at desks rather than at physical labor. Most diets— actual and recommended— are 35 to 40 percent

fat. The accompanying table shows the wide range of calories from fat in diets old and new.

HOW MUCH FAT IS IN TFIE DIET?

* About 50 percent saturated fat

Mostly olive oil

Mostly olive oil

About 33 percent saturated fat

About 33 percent saturated fat

If You Have Only Two Minutes to Learn About Fats, Read This

WHEN I STARTED TO LEARN about the intricate chemistry of fats, it was very exciting. I studied where plant and animal fats

come from and marveled at how the body makes its own fats. I wondered why the body tends to hoard polyunsaturated fats in

corn oil for a rainy day, while it burns the saturated fats in butter and coconut oil quickly. Unsatisfied with the charts

and tables in books, I drew my own and hung them over my desk. You can imagine my situation. I soon discovered that my friends

were less fascinated with fat metabolism than I was. They asked for the essential facts on fats. Here they are.

Members of the lipid family, fats and oils (which I will call fats) consist of individual fatty acids, which may be

saturated,

monounsaturated,

or

polyunsaturated

— terms describing their chemical structure. All fatty acids are strings of carbon atoms encircled by hydrogen atoms. When

every carbon atom bonds with a hydrogen atom, the fatty acid is

saturated.

If one pair of carbon atoms forms a bond, the fatty acid is monounsaturated. If two or more pairs of carbon atoms form a bond,

the fatty acid is pofyunsaturated. A carbon-hydrogen bond is known as a

saturated

or single bond. A carbon-carbon bond is called an

unsaturated

or double bond.

THE CHEMISTRY OF FATS

All fats consist of individual fatty acids made of hydrogen and carbon. Fatty acids may be saturated, monounsaturated, or

polyunsaturated.

Saturated

All carbon atoms form saturated bonds with hydrogen Example: stearic acid (beef and chocolate)

Monounsaturated

Two carbon atoms create one unsaturated bond Example: oleic acid (olive oil and lard)

Polyunsaturated

More than one pair of carbon atoms create two or more unsaturated bonds

Example: linoleic acid (corn oil)

All the fats we eat are a blend of saturated, monounsaturated, and polyunsaturated fatty acids. Fats are identified by the

predominant

fatty acid. Beef is mostly saturated, so we call it a saturated fat— even though it contains monounsaturated and polyunsaturated

fatty acids, too. Butter is mostly saturated, olive oil mostly monounsaturated, and corn oil mostly polyunsaturated. Lard

is difficult to characterize because it varies with the diet of the pig, but it's about 50 percent monounsaturated, 40 percent

saturated, and 10 percent polyunsaturated. Because it is 60 percent monounsaturated and polyunsaturated, lard is correctly

grouped with

un

saturated fats.

An important quality of every fatty acid is its ability to withstand heat. The more saturated the fat, the more sturdy it

is, because saturated bonds are stronger than unsaturated bonds. Delicate unsaturated bonds are easily damaged or oxidized

by heat. When you heat a fat to the smoking point, that's a sign of damage. Unsaturated fats also spoil more quickly than

saturated fats. Spoiled fats are called rancid.

Oxidized fats contribute to cancer and heart disease. According to

Science,

"Unsaturated fatty acids . . . are easily oxidized, particularly during cooking. The lipid peroxidation chain reaction (rancidity)

yields a variety of mutagens . . . and carcinogens."

2

At the University of Minnesota, researchers found that repeatedly heating vegetable oils including soybean, safflower, and

corn oil to frying temperature can create a toxic compound, HNE, linked to atherosclerosis, stroke, Parkinson's, Alzheimer's,

and liver disease.

3

"We are, it seems, biologically primed not to eat oxidated fat," writes Margaret Visser in

Much Depends on Dinner,

"for doing so can cause diarrhea, poor growth, loss of hair, skin lesions, anorexia, emaciation, and intestinal hemorrhages."

That's why it was bad news for health when fast-food restaurants stopped using saturated beef fat and palm oil, and started

frying foods in rancid polyunsaturated oils.