Real Food (24 page)

Authors: Nina Planck

Then, by chance, nature presented an experiment. When crop failure forced Tokelau islanders to move to New Zealand, they ate

less coconut oil, less fat, half as much saturated fat, and more polyunsaturated oils than at home. Good for the heart, right?

But in 1981, Prior found his subjects living in New Zealand in

worse

health: the immigrants had higher cholesterol, higher LDL, and lower HDL.

30

"The more an Islander takes on the ways of the West, the more prone he is to succumb to our degenerative diseases," Prior

said.

In the last thirty years, a number of studies have cleared coconut oil of any role in heart disease, and recent research confirms

those findings.

31

In 2002, researchers fed people seventy to eighty grams of medium-chain fats or vegetable oils daily and found no differences

in total cholesterol, VLDL, LDL, or HDL, or triglycerides.

32

Other researchers who fed medium-chain fats to rats stated bluntly, "The lipid [fats] theory of arteriosclerosis is rejected."

They noted that Sri Lanka, where coconut oil is the main fat, had low mortality from heart disease.

33

Coconut oil even improves the all-important ratio of HDL and LDL.

34

A study of Malaysians who ate palm, coconut, or corn oil for five weeks found that coconut oil increased HDL, improving the

ratio.

35

In the same study, saturated palmitic acid (found in another tropical fat, palm oil) lowered total cholesterol and LDL.

How, then, did coconut oil get a bad reputation? Partly because we misunderstood cholesterol. We used to think that any fat

that raised

total

cholesterol, as coconut oil can, was unhealthy, but now we know that total cholesterol is a poor predictor of heart disease

and that raising HDL is good. Moreover, hydrogenated coconut oil was used in some studies. In 1996, the lipids expert Mary

Enig explained that hydrogenation raises cholesterol: "Problems for coconut oil started four decades ago when researchers

fed animals hydrogenated coconut oil purposefully altered to make it devoid of essential fatty acids. Animals fed hydrogenated

coconut oil (as the only fat) became essential fatty acid-deficient; their cholesterol levels increased. Diets that cause

an essential fatty acid deficiency always produce an increase in cholesterol."

36

In 2001, researchers reported that partially hydrogenated soybean oil was worse than coconut oil. "Epidemiological and experimental

studies suggest that trans fatty acids increase risk more than do saturates because [trans fats] lower HDL," they wrote. "Solid

fats rich in lauric acids, such as tropical fats, appear to be preferable to trans fats in food manufacturing, where hard

fats are indispensable."

37

Big food companies may not be rushing to put coconut oil back in crackers, but you can put fresh coconut, dried flakes, and

coconut milk, cream, and oil in cookies, soups and curries. Many people take a spoonful of coconut oil daily to aid weight

loss and boost immunity.

Coconut oil comes in three unofficial grades. The best is unrefined or virgin oil, made by shredding and cold-pressing coconut

flesh while it is moist, a process called

wet milling.

The meat, milk, and oil are fermented for at least twenty-four hours while the water and oil separate. Finally, the oil is

gently heated to remove moisture and filtered. Virgin oil has the lovely flavor and scent of coconut.

The second-best coconut oil is expeller-pressed and gently deodorized to remove scent and flavor; it's a good choice if you

eat coconut oil for health but don't care for the flavor. Industrial coconut oil is made by extracting oil from

copra,

or dry coconut meat. To make it edible, the oil is refined, bleached, and deodorized, which destroys vitamins, scent, and

flavor.

I buy virgin coconut oil and cream, along with wonderful soap and moisturizer, from a cooperative of small growers in the

Philippines called Tropical Traditions. You can also find good brands of virgin coconut oil in whole foods shops, good groceries,

and Asian shops. Virgin coconut oil isn't cheap, but I don't use it every day, a little goes a long way, and it keeps for

two years without refrigeration. Canned coconut milk is less expensive. I like to have a couple of cans in the cupboard for

making a simple, creamy soup made of equal parts chicken stock and coconut milk, with sauteed ginger and cayenne. Everyone

loves it.

How the Margarine Makers Outfoxed the Dairy Farmers

THE ADVICE TO REPLACE BUTTER with margarine containing trans fats constituted a radical dietary experiment. Trans fats are

created when oil is hydrogenated. That's when unsaturated oil is blasted with hydrogen atoms, a form of artificial saturation

that makes the liquid oil solid, like natural saturated fats. But the similarity between trans fats and traditional saturated

fats ends there. Trans fats are new and dangerous. Traditional diets contain healthy saturated fats from both plants (like

coconut) and animals (butter), but until the twentieth century, no one ate trans fats, and now we know they cause heart disease.

1

Hydrogenated vegetable oils are widely used in cakes, cookies, donuts, chips, and crackers, for the same reason food companies

once used coconut oil: they're solid, heat-stable, and don't spoil easily. Though it's possible to hydrogenate any fat that

is not fully saturated (such as lard, which is about 60 percent unsaturated), most hydrogenated oils are made from polyunsaturated

vegetable oils such as canola, corn, and soybean. In a moment we'll come back to trans fats, but first, let's look at margarine,

the mother of hydrogenated oils.

In the nineteenth century, a patriotic French chemist, who had already earned gold medals for making bread with less flour,

invented margarine. A cattle plague having recently devastated European herds, "butter was difficult to get and expensive,"

writes Margaret Visser in

Much Depends on Dinner.

Napoleon III offered a prize for the invention of a cheaper substitute for butter. Tinkering on the imperial farm in Vincennes,

Hippolyte Mège-Mouriès won the prize in 1869, for his blend of beef fat and sheep stomach, with added milk for flavor.

This inexpensive, solid fat— known in English as oleomargarine— was taken up by the Dutch and English poor, who, like other

European peasants, couldn't afford butter. When the first U.S. oleomargarine plant opened in Manhattan in the 1870s, Americans,

blessed with ample green pastures, were in a better position: there was still plenty of butter to be had. Although the Chicago-based

meatpacking industry doggedly promoted oleomargarine as a cheaper substitute for butter, the unappealing white blocks were

not an overnight success with American cooks.

Dairy farmers, however, rightly saw a long-term commercial threat from this less expensive upstart and began to lobby furiously

for laws to restrict margarine sales. For example, they stopped it from ever being called "butter." Margarine makers fought

back, proposing, quite sensibly, to dye margarine yellow to make it look like butter. Color had always been the buyer's clue

to butter quality. Grass-fed butter, rich in vitamin A, is yellow, while butter from grain-fed cows is white.

With the help of friendly politicians, dairy farmers put a stop to yellow dye, and five states with dairy muscle even forced

margarine makers to dye it pink, apparently intending to make it look ridiculous. Undeterred, margarine makers responded by

selling the white blocks with a packet of yellow dye to mix in at home. This, presumably, would fool the family— if not the

cook.

"On the whole," writes Visser, "the producers of butter fought a very dirty fight." But in vain. After a series of skirmishes,

the dairy industry gradually lost clout, while the power of margarine manufacturers grew. By 1950, President Harry Truman

had repealed the last of the antimargarine laws, and punishing taxes on margarine were lifted. The modern margarine business

was off and running.

Meanwhile, a revolutionary method for making solid fats was soon to transform the margarine industry, according to the food

writer Linda Joyce Forristal, who is famous for lard pie crusts and better known as Mother Linda.

2

In the late 1890s, the soap and candle company Proctor & Gamble was fed up with the high price of lard and tallow— the market

was controlled by the powerful meatpacking industry— and began to look for alternatives. It settled on cottonseed oil and

in classic capitalist fashion soon owned eight cottonseed plants in Mississippi, the better to secure its supply. In 1907,

company scientists figured out how to make liquid oil solid by firing it with hydrogen. "Mindful that electrification was

forcing the candle business into decline, P&G looked for other markets for their new product," explains Forristal. "Since

hydrogenated cottonseed oil resembled lard, why not sell it as a food?"

Introduced in 1911, the new product was presented as healthier, cheaper, and cleaner than butter and lard. Proctor

&c

Gamble promoted the spreadable white vegetable fat in women's magazines and gave away a cookbook with 615 recipes calling

for its brand name: Crisco. The marketing department spent time on Jewish cooks in particular. Crisco made it easier to keep

kosher because it was like butter but could be eaten with meats, and it was also a substitute for lard.

Then, in the 1950s, came another fillip for plucky, can't-knock-me-down margarine: official advice that saturated fats were

unhealthy. The makers of Crisco and the vegetable oil industry worked to spread the word that animal fats caused heart disease.

Food companies and restaurants came under pressure to stop using coconut oil, butter, and lard. With hydrogenation, the vegetable

oil industry could offer what seemed to be the ideal fat: polyunsaturated, yet solid and shelf-stable. And that, dear reader,

is how trans fats pushed lard and butter out of American kitchens.

A RECIPE FOR MARGARINE

Begin with a polyunsaturated, liquid vegetable oil rancid from extraction under high heat. Any oil will do, but about 85 percent

of hydrogenated oils are soybean. Mix with tiny metal particles, usually nickel oxide. In a high-pressure, high-temperature

reactor, shoot hydrogen atoms at the unsaturated carbon bonds. Add soaplike emulsifiers and starch to make it soft and creamy.

Steam to remove foul odors, bleach away the gray color, dye it yellow, and add artificial flavors. If you prefer real food,

but you like a soft spread, try this idea from Fran McCullough: mix equal parts room-temperature butter and olive oil until

creamy. Add unrefined salt to taste.

As we now know, the experiment with margarine ended badly, spectacularly so. Trans fats wreak havoc all over the body, and

for a long time, these dangerous fats were hard to detect. Nutrition labels listed saturated and unsaturated fats, but the

careful consumer had to read the ingredient list for "hydrogenated" or "partially hydrogenated" oils to avoid trans fats.

In 2006, things got easier, when the FDA required food labels to list trans fats. "The minute it goes on the label, it's out

of the food supply," said Dr. Marion Nestle, a professor at New York University. "That's how food policy is done in this country."

How Fake Butter Causes Heart Disease

[Trans fats are the] biggest food-processing disaster in U.S. history . . . In Europe [food companies] hired chemists and

took trans fats out . . . In the United States, they hired lawyers and public relations people.

—Professor Walter Willett,

Harvard School of Public Health

IN THE LAST CENTURY, the American diet changed radically, but

how

it changed might surprise you. Given that heart disease began to be a problem around 1950, you might guess that we eat more

saturated fats than in 1900. But in fact we eat less butter, lard, and beef and vastly more polyunsaturated oils now. In another

way, however, the assumption that we eat more "artery-clogging" saturated fats is dead right: today we eat an industrial saturated

fat that didn't exist in 1900. Before World War II, Americans ate about 12 grams of trans fats daily, by 1985 as much as 40

grams.

3

Since the 1970s, Americans have eaten roughly twice as much margarine as butter. For a major cause of heart disease, look

no farther. Lard and butter "aren't public enemy No. 1 anymore," says Dr. Frank Hu of the Harvard School of Public Health.

That designation now belongs to trans fats.

According to Dr. Walter Willett at Harvard, trans fats cause up to one hundred thousand premature deaths annually from heart

disease.

4

Compared with saturated fat, trans fats raise triglycerides, reduce blood vessel function, and raise lipoprotein (a) (Lp(a)),

which causes clots and atherosclerosis.

5

They raise LDL and reduce HDL. Willett says trans fats are twice as bad for the HDL/LDL ratio as saturated fats. Even experts

who are cautious about saturated fat agree that butter is better.

I find it dismaying that the dangers of trans fats were known for sixty years. Weston Price cited 1943 research that butter

was better than hydrogenated cottonseed oil. In the 1950s, researchers guessed that hydrogenated vegetable oil led to heart

disease.

6

Ancel Keys, the proponent of monounsaturated fat, showed in 1961 that hydrogenated corn oil raised triglycerides more than

butter.

7

Year after year, the bad news piled up.

One dogged researcher, Mary Enig, helped to get the word out. The author of

Know Your Fats,

Enig waged an often lonely battle. I'm afraid her efforts were not always welcomed with bouquets of roses. In 1978, Enig wrote

a scientific paper challenging a government report blaming saturated fat for cancer, in which she pointed out that the data

actually showed a link with trans fats. Not long after, "two guys from the Institute of Shortening and Edible Oils— the trans

fat lobby, basically— visited me, and boy, were they angry," Enig told

Gourmet

magazine.

8

"They said they'd been keeping a careful watch to prevent articles like mine from coming out and didn't know how this horse

had gotten out of the barn."

The stakes were high. "We spent lots of time, and lots of money and energy, refuting this work," said Dr. Lars Wiederman,

who once worked for the American Soybean Association. "Protecting trans fats from the taint of negative scientific findings

was our charge."

TRANS FATS: UNSAFE AT ANY MEAL

• Lower HDL

• Raise LDL

• Raise Lp(a), which promotes atherosclerosis and clotting

• Reduce blood vessel function

• Promote obesity, diabetes, and hypertension

• Alter fat cell size and number

• Reduce cream in breast milk

• Reduce fertility and correlate with low birth weight

• Increase asthma

• Reduce immune response

• Interfere with the conversion and use of DHA and EPA

• Disrupt enzymes that metabolize carcinogens and drugs

• Damage cell membranes

• Create free radicals

Main source: Enig Associates.

At Harvard, meanwhile, Willett and his colleagues produced definitive studies on trans fats, providing data that proved crucial

in convincing the government that trans fats were unsafe. In 1999, Willett described how the food industry had tried to delay

the guilty verdict.

Food manufacturers use partial hydrogenation of vegetable oil to destroy some fatty acids, such as linolenic and linoleic

acid, which tend to oxidize, causing fat to become rancid. Commercial production of partially hydrogenated fats began in the

early 20th century and increased steadily until about the 1960s as processed vegetable fats displaced animal fats in the diet.

Lower cost was the initial motivation, but health benefits were later claimed for margarine as a replacement for butter .

. . Trans fats [are] associated with an increased risk of coronary heart disease. In response to these reports, a 1995 review

sponsored by the food industry concluded that the evidence was insufficient to take action and further research was needed.

9

Fortunately for the public, researchers did carry on. Unfortunately for the trans fat lobby, the news got worse. At last,

official word came from the National Academy of Sciences, which announced in 2002 that trans fats have "no known health benefits"

and no level of consumption is safe.

10

As the list in the preceding sidebar shows, trans fats do a lot of damage in addition to causing heart disease. Recall that

all of your cell walls are made of fat. Like natural fats, trans fats enter the tissues and become part of the cell membrane,

where, unlike natural fats, they disrupt every cellular activity, from metabolism to immunity. Hundreds of thousands of Americans

are walking around with cell walls made of trans fats, which have no place in the diet or the body. The deadly effects of

industrial trans fats will be with us for some time. The sooner we ban trans fats— as Denmark has— the better.

11

Why I Don't Eat Corn, Soybean, or Sunflower Oil

SINCE THE 1970s, experts have urged us to eat less fat and to replace saturated fats with polyunsaturated oils. Did Americans

do as they were told? Yes and no. In 2000, we ignored official advice and ate more total fat than before. In the low-fat era,

this may be surprising; larger portions of junk foods and plain old gluttony probably played a part. We did eat more vegetable

oils, as instructed. Perhaps we were simply obedient and used more vegetable oils in cooking, but I suspect Americans didn't

always choose the polyunsaturated oils now ubiquitous in cookies, crackers, and other processed foods. Sometimes, the food

supply changes, not only without our say-so, but without our being the wiser. In this case, cheap vegetable oils (often hydrogenated)

were the ingredient the food industry chose, and those were the fats we got.

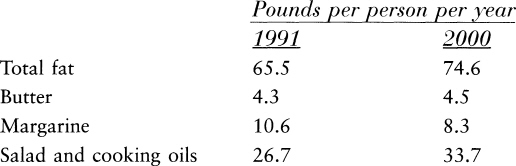

REAL FOOD U.S. CONSUMPTION OF FATS AND OILS