Real Food (29 page)

Authors: Nina Planck

HOW CACAO BEANS BECOME CHOCOLATE

First cacao beans are removed from the pods. The best chocolate makers ferment the beans to develop flavor. Next the beans

are roasted (again for flavor), shelled, and broken up into little shards called nibs. Nibs are then ground and heated to

make cocoa liquor. If you remove all the cocoa butter from the liquor, what's left is pure cocoa powder. If you add more cocoa

butter, plus sugar and vanilla, to the liquor, you get a chocolate bar.

The cacao tree is an unusual plant. Cocoa powder contains large amounts of calcium, copper, magnesium, phosphorus, and potassium,

and more iron than any vegetable. It is very rich in polyphenols, particularly a group called flavonoids, which account for

the rich pigment in red wine, cherries, and tea. These antioxidants promote vascular health, prevent LDL oxidation, lower

blood pressure, reduce blood clots, and fight cancer. A one-and-a-half-ounce (40-gram) bar of milk chocolate contains as many

antioxidants as a five-ounce (150-ml) glass of red wine. Polyphenols are found in cocoa solids, not cocoa butter. Thus pure

cocoa powder has the most antioxidants by weight, then dark chocolate, and finally milk chocolate. White chocolate— made of

cocoa butter without any cocoa powder— has none at all.

The polyphenols in chocolate may prevent obesity, diabetes, and high blood pressure— all risk factors for heart disease. In

2005, the

American Journal of Clinical Nutrition

reported that eating three and a half ounces (100 grams) of dark chocolate daily decreased blood pressure and significantly

improved sugar metabolism by increasing sensitivity to insulin. Insulin sensitivity is desirable; recall that in diabetes,

the cells are deaf to insulin. White chocolate did not have the same effect.

29

ANTIOXIDANTS IN CHOCOLATE AND OTHER FOODS

Each of the following contains about 200 milligrams of polyphenols. Note that chocolate from fermented beans contains more

polyphenols, and dark chocolate contains more polyphenols than milk chocolate.

• 1.5 oz milk chocolate

• 1 glass red wine (5 oz)

• 12 glasses white wine (5 oz each)

• 2 cups tea

• 4 apples

• 5 servings of onions

• 3 glasses black currant juice

• 7 glasses of orange juice

Source: John Ashton and Suzy Ashton,

A Chocolate a Day Keeps the

Doctor Away.

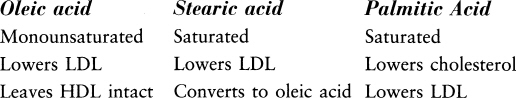

The fats in chocolate— mostly monounsaturated and saturated— are also healthy. Chocolate is unctuous because cocoa butter

melts at mouth temperature. The better chocolate bars have added cocoa butter, which is roughly equal parts stearic, palmitic,

and oleic acid. Extra stearic acid is converted to oleic acid, so the net effect of these fats is good for cholesterol. A

2004 study in

Free Radical Biology and Medicine

found that chocolate increased HDL and reduced oxidation of cholesterol. Oxidized cholesterol causes atherosclerosis. Chocolate

keeps well because saturated fats are stable, and any oxidation from heat or light is inhibited by cocoa's abundant polyphenols.

COCOA BUTTER IS GOOD FOR YOUR HEART

Is chocolate addictive? The Chocolate Information Center— a research lab funded by the Mars company— prefers to call the craving

for chocolate a "strong desire." "Theoretically," its scientists write cautiously, chocolate could "contribute to feelings

of well-being." Chocolate contains the stimulants theobromine and caffeine; tyramine and phenylethylamine, which are uppers;

and anandamide, which mimics cannabinoids, natural pain killers. (Anandamide derives from the Sanskrit

ananda,

"internal bliss.") But the chocolate scientists note that these natural drugs are found only in trace amounts in chocolate.

Moreover, they are also found in many foods we don't crave. Caffeine is an exception; it is certainly habit-forming, but there

is much more caffeine in coffee and tea than in chocolate.

Craving a certain food is sometimes regarded as signaling an acute nutritional deficiency, but in the case of chocolate, I'm

not convinced. Chocolate is rich in magnesium. If a woman needs— and thus craves— magnesium before her period, she might just

as easily have a strong desire to eat magnesium-rich foods, like broccoli, tofu, and kidney beans. Rushing to the corner shop

for broccoli, however, is not part of PMS folklore.

What often goes unmentioned in discussion about the desire for chocolate is sugar. I suspect that sugar plays a large part

in the urge to finish a bar of chocolate once you've torn into it. Sugar quickly brings on a gentle high, which is why so

many people crave it in low moments. Unfortunately, the high is often followed by a crash.

Studies show that capsules containing the compounds in cocoa don't satisfy the desire as well as real chocolate, which strongly

suggests that the aroma, flavor, and creaminess of chocolate, more than any mood-enhancing chemicals, are key factors in chocolate

craving. In

Chocolate: A Bittersweet Saga of Dark and Light,

Mort Rosenblum considers all these factors, including the mood-enhancing agents in chocolate, and concludes that chocolate

fails the two tests of addiction: "It is not dangerous to the human organism. And no symptoms of withdrawal appear when consistently

high consumption is abruptly stopped."

NAKED CHOCOLATE

Nibs are little pieces of fermented, roasted, and shelled cacao beans— the raw material of all chocolate. More like nuts than

candy, crunchy nibs are about half cocoa butter. They have a tannic flavor, like espresso or red wine. Try them in place of

chocolate chips in cookies and brownies or sprinkle on ice cream. Toss nibs on roasted pumpkin or add to Mexican mole. They

pack a little jolt of caffeine.

How much chocolate is good for you? John Ashton and Suzy Ashton, the authors of

A Chocolate a Day Keeps the Doctor Away,

who are unabashed enthusiasts, recommend no more than two ounces (55 grams) of chocolate each day, preferably dark chocolate,

which has less sugar and more antioxidants. It also has more flavor than milk chocolate, which is why connoisseurs the world

over prefer it. Once you're used to the bold, complex flavors of chocolate unmasked by sugar, the average milk chocolate will

seem cloying. Not, I hasten to add, that there is anything wrong with milk, which goes very nicely with chocolate. After all,

ganache is nothing more than blended cream and chocolate. If you like milk chocolate, look for a bar with more cocoa than

sugar, such as one made by Scharffen Berger, which is 41 percent cocoa, about twice the amount in a typical bar.

Sugar makes me fat and grumpy, so gradually I weaned myself from dark (70 percent cocoa) to very dark (85 percent) chocolate

bars. Occasionally, I will make a cup of cocoa with unsweetened chocolate and very fresh grass-fed raw cream, which is just

sweet enough to balance the bitterness. Do buy the best unsweetened and dark chocolate you can afford; without sugar there

is no concealing shoddy chocolate. Cheap chocolate can be bitter or metallic.

With chocolate desserts I recommend the same thing: less sugar. When you make chocolate mousse (or any dessert), use half

the sugar called for. You will taste the chocolate first, instead of the sugar. When sweetness is not the dominant sensation,

your appreciation for a particular flavor will grow; chocolate may seem fruity, smoky, or herbal, for example. Other flavors

will change subtly, too. Next to dark chocolate, savory foods such as almonds, coconut, and cream are almost sweet. If you're

used to sugary desserts, you may find "half-the-sugar" desserts not quite to your taste at first. But I swear by this rule

of thumb. I follow it every time I try a new recipe for ice cream or pumpkin pie or anything else. As my mother likes to say,

"If it's sweet on the first bite, it will be too sweet by the last."

WHEN I TOLD MY FRIEND Wendell Steavenson, an Anglo-American writer, I was writing a book about why butter is good for you,

her comment was typically arch. "Cholesterol," she said, mock solemn, "only

exists

in America." I knew exactly what she meant. In much of the world— perhaps Wendy was thinking of London, Baghdad, Beirut, or

Tbilisi, to name but a few cities where she has lived— people aren't morbidly afraid of traditional foods like cream and lamb.

Not yet, anyway.

The American anticholesterol campaign, which British experts gently mock as "know-your-number" medicine, baffles foreigners.

Here at home, it mostly inspires anxiety. When you sit down to eat with health-conscious Americans, the subject of cholesterol

is hard to avoid, but the conversation seldom moves beyond weak jokes about clogged arteries.

We have been taught to fear this scoundrel called cholesterol, and fear it we do, yet most people have no idea what cholesterol

is. It is often called a fat, but cholesterol is actually a sterol, a kind of alcohol. Cholesterol is part of all animal cell

membranes. It makes up much of brain and nervous tissue, and it's an important part of organs including the heart, liver,

and kidney. It is so vital to the developing brain that defects in cholesterol metabolism cause mental retardation.

1

Cholesterol is necessary to make vitamin D, bile acids (which digest fats), adrenal hormones, and the sex hormones estrogen

and testosterone.

These roles are well known, at least to cholesterol experts. Then, in a college textbook, I came across a striking statement:

cholesterol is a

repair

molecule. At first I didn't understand it— or quite believe it. After all, cholesterol is known for doing damage, not healing.

But apparently that's not quite how cholesterol works. Let me explain by introducing the famous lipoproteins.

Low-density lipoprotein (LDL), often called the "bad" cholesterol, and its counterpart, high-density lipoprotein (HDL), or

"good" cholesterol, are not forms of cholesterol at all, but vehicles. Like little boats with a waxy cargo, LDL and HDL ferry

cholesterol around the body. LDL carries cholesterol from the liver to the tissues (including blood), and HDL carries cholesterol

from the tissues back to the liver.

2

In every healthy person, the lipoproteins help cholesterol go about its chores, digesting fats here and making estrogen there.

The body needs both LDL and HDL. According to the

Journal of American Physicians and Surgeons,

the "good" and "bad" cholesterol story is "overly simplistic and not supported by the evidence."

3

Repair is one of cholesterol's many tasks. When arterial walls are damaged, cholesterol rushes to the scene on a dinghy piloted

by LDL to fix them.

4

As the authors of

Human Nutrition and

Dietetics

describe low-density lipoproteins, "their role is to deliver cholesterol to tissues for the vital functions of membrane synthesis

and repair." In

Know Your Fats,

Mary Enig writes: "Cholesterol is used by the body as a raw material for the healing process. This is the reason injured areas

in the arteries (as in atherosclerosis) or the lungs (as in tuberculosis) have cholesterol along with several other components

(such as calcium and collagen) in the 'scar' tissue [they've] formed to heal the 'wound.'"

This would explain why high LDL is sometimes linked to heart disease. Many people with heart disease have damaged arteries,

and cholesterol travels on LDL to heal them. Just because you see fire fighters at burning buildings does not mean they start

fires.

Cholesterol comes from two sources. The body makes cholesterol in the brain and the liver, which makes about 1,500 milligrams

daily. The other source is the diet. Only animal foods contain cholesterol. It is stored in the fat of dairy foods and the

muscle of animal protein. Thus beef, pork, and poultry, although they vary in fat content, have similar amounts of cholesterol

(about 20 milligrams per ounce). That means trimming the fat from meat will reduce the fat but not cholesterol content, whereas

skim milk contains less cholesterol than whole milk. Egg yolks and milk are particularly rich in cholesterol because baby

animals need large amounts to build brain cells.

Experts once thought that eating cholesterol raised blood cholesterol. In 1968, they advised us to limit dietary cholesterol

to 300 milligrams daily. This figure was not only unrealistic— with 275 to 300 milligrams of cholesterol, eating one egg would

put you at or near the limit— but also arbitrary, as Gina Mallet discovered. Now we know that blood cholesterol is largely

determined by metabolism— how the body makes, uses, and disposes of cholesterol. "The amount of cholesterol in food is not

very strongly linked to cholesterol levels in the blood," says a report from the Harvard School of Public Health.

5

How much cholesterol do you need to eat? In theory, none; your body will make enough. But there are good reasons to consume

cholesterol, which is harmless in its natural form. First, infants and children under two don't produce enough; cholesterol

must

be part of their diets, which is why breast milk has plenty.

6

The second reason to consume cholesterol applies to all ages: avoiding it entirely would mean shunning highly nutritious

foods. Liver, meat, shrimp, butter, and eggs offer complete protein, omega-3 fats, and vitamins A, B

12

, and D— all vital nutrients not found in plants. It is not possible to separate the cholesterol from the nutrients in these

foods. Older people may even benefit from eating cholesterol. In 1995, researchers found that cholesterol in eggs aids older

people with declining memory.

7

The body aims to keep cholesterol levels steady. Thus the more cholesterol you eat, the less the liver makes, and the less

you eat, the more the liver makes. That explains why vegans and vegetarians, who eat few animal foods or none at all, can

have high cholesterol. Moreover, up to 50 percent of cholesterol is determined by genes, not diet.

8

As people with a family history of high blood cholesterol know, diet has little effect on blood levels.

If you have normal cholesterol metabolism, you may eat real foods without fear. As we've seen, people who eat traditional

foods rich in cholesterol and saturated fat don't have high cholesterol or more heart disease. Other traditional foods, meanwhile,

have salutary effects on health in general and heart disease in particular; they include fish, red wine, chocolate, and olive

oil.

Industrial foods are the real villain in heart disease. The main offenders are trans fats, corn oil, and sugar. As we've seen,

trans fats promote atherosclerosis and clotting; polyunsaturated vegetable oils lower HDL; and sugar depletes B vitamins and

raises triglycerides. All these effects are bad for the heart. The actual culprits are easy to spot for anyone who cares to

read more than casually about diet and heart disease. So why did a perfectly useful molecule called cholesterol, which we've

been consuming in liver, eggs, and shrimp for three million years, take the fall?

How Cholesterol Became the Villain

THE IDEA THAT DIET contributes to heart disease is not new. In 1908, a young Russian medical researcher, M. A. Ignatovsky,

fed rabbits a diet of animal protein, and when the bunnies developed arteriosclerosis, he blamed the protein. In 1913, a group

of rival doctors followed by feeding cholesterol to rabbits, with similar results, including fat and cholesterol deposits

in arteries, and they guessed that cholesterol, not protein, was responsible for the arteriosclerosis in Ignatovsky's rabbits

as well as theirs.

Animal experiments can, of course, be very useful, but in this case researchers may have reached the wrong conclusions. Unlike

humans, who are born to eat cholesterol, rabbits are herbivores with no ability to metabolize it. When you force-feed rabbits

with cholesterol, their blood cholesterol rises ten or twenty times higher than the highest values ever seen in humans; the

effect is like poisoning. "Cholesterol is deposited in the arteries of the rabbit, but these deposits do not even remotely

resemble those found in human atherosclerosis," says Dr. Uffe Ravnskov, the author of

The

Cholesterol Myths.

Later, in human trials, researchers

deliberately

used oxidized cholesterol to demonstrate that dietary cholesterol causes atherosclerosis.

Oxidized cholesterol, like oxidized or rancid polyunsaturated vegetable oil, is damaged and unhealthy. As I've mentioned elsewhere,

it's no secret in cholesterol circles that oxidized cholesterol, found in powdered eggs, powdered milk, and fried foods, causes

arterial plaques.

9

Dr. Kilmer McCully, author of

The Heart Revolution,

says that "pure cholesterol, containing no oxy-cholesterols, does not damage arteries in animals."

Nevertheless, by the 1950s the cholesterol theory was well established: it was thought that eating cholesterol raises blood

cholesterol and causes arteriosclerosis. Then, in a significant development, researchers concluded that cholesterol was not

acting alone. The revised cholesterol theory had two parts: first, saturated fats (as opposed to unsaturated fats) raise cholesterol,

and second, elevated cholesterol causes arteriosclerosis.

Ancel Keys, the professor we met in an earlier chapter on fats, led the campaign against saturated fats. A prolific writer

and speaker, Keys spent his last years in Naples, presumably enjoying the Mediterranean diet he had become famous for promoting.

When he died in 2004, at the age of one hundred, his influence on diet and disease was rightly considered vast. Theodore Van

Itallie wrote this tribute in

Nutrition and Metabolism:

"For those of us who worked . . . to call attention to the relationship of serum total cholesterol to risk of coronary heart

disease (CHD), and to the cholesterol-raising effects of certain saturated fats, Keys will always be one of the major prophets

who provided the early evidence that atherosclerosis is not an inevitable concomitant of aging, and that a diet high in saturated

fat . . . can be a major risk factor for CHD."

10

In the 1950s, Keys made a series of contradictory statements about fats.

11

He said that all fats raise cholesterol; yet elsewhere, he wrote that saturated fats raise cholesterol and polyunsaturated

oils lower it. Keys said that animal fats caused heart disease; elsewhere, he wrote there was no difference between animal

fats and vegetable oils in their effects. Clearly, his data were inconsistent. Nevertheless, Keys focused on one hypothesis:

that a diet high in fat and saturated fat caused heart disease.

In 1953, Keys published a famous paper known as the Six Countries Study, placing fat and cholesterol at the center of the

debate about diet and heart disease. Keys presented a diagram of fat consumption and death from heart disease in six countries;

it appeared to show that the more fat people ate, the more deaths from heart disease. Japan was at the low end of the graph,

which swept smoothly upward, and the United States was at the top. But the diagram didn't tell the whole story. There were,

in fact, data on fat and heart disease from twenty-two countries, but Keys omitted the other sixteen.

12

Instead of forming a convincing upward curve, the twenty-two data points were scattered all over. He declined to cite Finland

and Mexico, for example, where fat consumption was similar. Finland had seven times the rate of heart disease as Mexico.

In 1970, Keys published another famous paper— the Seven Countries Study— which appeared to demonstrate a link between cholesterol

and heart disease in fifteen populations in seven countries. "The correlation is obvious," said Keys. But when Ravnskov plotted

Keys's raw data into a graph, the correlation fell apart. The link is even weaker when you compare groups within countries.

On the Greek island of Corfu, for example, people died five times more often from a heart attack than their fellow Greeks

living on nearby Crete, although cholesterol on Corfu was lower.

Keys was undeterred and went on to advocate what he called the Mediterranean diet. "The heart of what we now consider the

Mediterranean diet is mainly vegetarian," he wrote. "Pasta in many forms, leaves sprinkled with olive oil, all kinds of vegetables

in season, and often cheese, all finished off with fruit and frequently washed down with wine." But the traditional Mediterranean

diet is not chiefly vegetarian; beef, lamb, goat, pork, game, poultry, liver, and fish are common fare.

Pork— to name only one meat— is eaten throughout the region, where pigs (never fussy eaters) thrive on scrubby land. Italy

and Spain are famous for cured pork (prosciutto and serrano ham) and for sausages, which require extra lard. The Spanish make

sweet lard cakes called

mantecados,

while Italian bakers use

strutto

(rendered lard) much the way American and British cooks once did. In Tuscany,

lardo di

Colonnata

— lard aged in marble with herbs— is eaten straight. In France, warm pork fat dressing and some kind of bacon are de rigueur

in the classic salads

pissenlit

au lard

and

frisee aux lardons,

made with the bitter greens dandelion and endive, respectively.

Olive oil is also traditional in the Mediterranean, of course. It's eaten liberally on Crete, for example. ("My God, how much

oil you use!" Keys is said to have exclaimed when he saw a green salad drowning in olive oil on the island.) But traditional

Mediterranean cuisine includes many other fats, too. In northern Italy, butter is typical, and lard is eaten in central regions.

In sprawling Provence, which spans the Mediterranean coast and the Alps, olive oil and lard are common, and Gascons are famous

for duck and goose fat.