Real Food (25 page)

Authors: Nina Planck

Source: USD A Agricultural Statistics, 2003.

Perhaps you're thinking what I thought when I first saw these figures: vegetable oils are a good source of omega-6 linoleic

acid (LA), one of the essential fats. What's wrong with that? In modest amounts, nothing. But we eat far too many. The balance

between the two essential fats, omega-3 and omega-6, is out of whack. We should eat equal amounts, but the industrial diet

has about twenty times more omega-6 than omega-3 fats. For three million years, no human ate like that.

The flood of omega-6 fats comes from the American heartland, once known for rippling wheat fields. This lovely image is outdated.

Today the bread basket is more like an oil field, studded with rigs spewing soybean and corn oil. (And corn syrup and starch.

The writer Michael Pollan calls corn "the keystone species of the industrial food system.")

12

The heartland oils are fountains of omega 6 fats. Soybean oil is 53 percent omega-6, corn 57 percent, sunflower 68 percent,

and safflower 78 percent. Corn oil contains sixty times more omega-6 than omega-3 fats. In safflower oil, the ratio is 77:1.

That's a long way from the ideal ratio of 1:1.

"The current Western diet is very high in omega-6 fats because of the indiscriminate recommendation to substitute omega-6

fats for saturated fats to lower serum cholesterol," says Dr. Artemis Simopoulos, author of

The Omega Diet.

Industrial farming has made things worse: "Intake of omega-3 fats is much lower today because of the decrease in fish consumption

and the industrial production of animal feeds rich in grains containing omega-6 fats, leading to production of meat rich in

omega-6 and poor in omega3 fats. The same is true for cultured fish and eggs."

13

What's wrong with eating too many omega-6 fats? From the omega fats, the body makes chemicals called eicosanoids, hormonelike

agents with far-reaching effects on metabolism, inflammation, immunity, fertility, blood pressure, skin, vision, and mood.

"Eicosanoids are involved from the top of the head in the brain to the nerves at the bottom of the feet and everywhere in

between," writes Kenneth Broughton, a professor of nutrition at the University of Wyoming.

14

Omega-3 and omega-6 eicosanoids play opposite and equally vital roles. Omega-3 eicosanoids are anti-inflammatory and calming,

for example, while omega-6 eicosanoids are inflammatory and reactive. Late in pregnancy, omega-6 eicosanoids prompt labor

to begin and omega-3 fats prevent premature birth. Omega6 agents suppress, and omega-3 agents promote, ovulation.

15

By promoting clotting, omega-6 eicosanoids stop you from bleeding to death from a small cut. Omega-3 eicosanoids, on the

other hand, thin the blood, which helps prevent heart attack and stroke. (There is one notable exception: the omega-6 fat

GLA tends to behave more like an omega-3, fighting inflammation and heart disease. GLA is in the oils of black currant, borage,

evening primrose, and Siberian pine nut.)

Imagine a body dominated by omega-6 eicosanoids; symptoms would include inflammation, obesity, insulin resistance, premature

labor, infertility, blood clots, and depression. As for heart disease, omega-6 eicosanoids are trouble. They promote inflammation,

constrict blood vessels, and encourage platelet stickiness and clotting. Oxidized omega-6 fats lead to oxidized LDL, which

causes atherosclerosis.

16

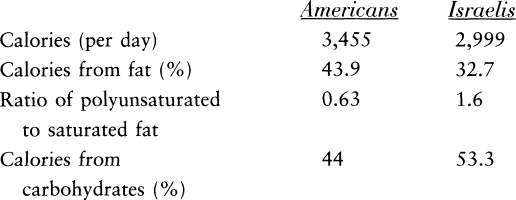

Omega-6 fats are the key to a mystery scientists dubbed the "Israeli Paradox." In 1996, researchers noted that Israeli Jews

followed the recommended diet for preventing obesity, diabetes, and heart disease.

They ate fewer calories, more carbohydrates, less fat, less saturated fat, and more polyunsaturated vegetable oils than Americans.

In fact, their diet closely resembled the USDA food pyramid, including generous amounts of fruit and vegetables. Notably,

they ate more omega-6 fats than any group in the world. The reward for this dietary discipline? Higher rates of obesity and

diabetes than Americans and similar rates of heart disease. "Rather than being beneficial," said researchers, "high omega-6

polyunsaturated fatty acid diets may have some long-term side effects within the cluster of hyperinsulinemia, atherosclerosis,

and tumorigenesis."

17

In plain words, omega-6 fats lead to diabetes, heart disease, and cancer. There is strong evidence that omega-6 fats make

cancer cells grow faster.

18

FAT CONSUMPTION IN U.S. AND ISRAELI POPULATIONS

Israelis eat less fat and more polyunsaturated oils than Americans, yet they have higher rates of obesity and diabetes and

similar rates of heart disease. Scientists blame excess omega-6 LA.

Source: Susan Allport, "The Skinny on Fat,"

Gastronomica

3, no. 1 (2003): 28-36.

Americans are on the same unhealthy track. We eat too many vegetable oils, too few natural saturated fats, and too many refined

carbohydrates, which raise triglycerides. This is new. When our ancestors ate grains and omega-6 fats, they came from whole

foods: leafy plants, whole wheat, and corn. Native Americans rarely, if ever, ate pure corn oil. They ate the whole corn kernel:

bran, carbohydrate, oil, and all. Corn was ground slowly between stones, leaving its unsaturated fats and antioxidant vitamin

E intact. People ate whole grains and fresh, unrefined oils.

Industrial vegetable oil processing, by contrast, removes flavor and nutrients. Grain, beans, and seeds are crushed under

high heat and extracted with chemical solvents like hexane, which is then boiled off. They may be bleached, refined, and deodorized.

All this damages the polyunsaturated fats, destroys vitamin E, and creates free radicals.

Modern vegetable oils are not my idea of real food. Corn, safflower, soybean, and sunflower oil have little flavor, which

is reason enough not to eat them. Moreover, they don't contain any important nutrient that I can't find in some other traditional

food. You can get all the vitamin E you need from almonds, avocados, and whole grains, and more than enough omega-6 fats from

olive oil.

IN THE ANNALS OF OILS, canola oil is worth a little detour, because it is a unique vegetable oil and much celebrated by advocates

of the "heart healthy" diet. Perhaps the most famous modern vegetable oil, canola is made from rapeseed, a member of the genus

Brassica,

which includes broccoli and cabbage. Unusually for a seed oil, it's rich in monounsaturated fat, with some omega-3 fats, too.

In recent years, Americans have added huge amounts of canola oil to their diets. In 1992, the United States imported 381,000

metric tons of canola oil; in 2001, 540,000 tons came in.

Traditional rapeseed oil has a long history of culinary use in China and India, where the seeds were ground between stones

and they used the oil fresh, probably in relatively small quantities, given the slow method of making oil. Unfortunately,

much of the fat (about 50 percent) in rapeseed is erucic acid, which causes lesions on the heart. Scientists have long been

aware of the erucic acid problem, and in the 1970s they bred a new rapeseed oil low in erucic acid. They called it canola,

for Canadian oil.

This new rapeseed oil is typically about 60 percent monounsaturated oleic acid, 20 percent polyunsaturated omega-6, 10 percent

polyunsaturated omega-3, and most of the rest is saturated. With this combination of fats, canola oil was promoted as good

for the heart and sales grew quickly. Official dietary advice and cookbooks were key to the campaign, with many recipes calling

for heart-friendly monounsaturated canola oil to lower cholesterol. In 1985, canola oil won GRAS status— Generally Recognized

as Safe— from the FDA. Highly coveted, GRAS means that a company doesn't have to prove an ingredient is safe each time it

is added to foods.

However, canola oil isn't perfect. The ratio of omega-6 to omega-3 fats in canola oil (2:1) is not ideal— but it's not terrible,

either. As we've seen, an equal amount of omega-6 and omega-3 fats is best. Like other modern vegetable oils, most canola

oil is refined under heat and pressure, which damages its omega-3 fats. Because canola oil is more easily hydrogenated than

some vegetable oils, it is often used in processed foods. Finally, much of the low-erucic acid canola oil crop is genetically

engineered.

It's difficult to find neutral information on canola. Its fans and critics are equally firm. For obvious reasons, there are

no long-term studies: low-erucic acid canola oil is a relatively new food. Many of the alarming claims making the rounds are

probably overstated, and I won't repeat them here. However, animal studies have linked canola oil with reduced platelet count,

shorter life span, and greater need for vitamin E. The United States and Canada do not permit canola oil to be used in infant

formula because it retards growth in animals. In one human study, canola oil raised triglycerides (fats that are part of the

"total cholesterol" number) while saturated fats lowered triglycerides.

19

Despite these caveats, many nutritionists are enthusiastic about canola oil for its monounsaturated fats. Loren Cordain, the

expert on Stone Age diets, favors canola oil, even though it is a very modern food. "There is no credible scientific evidence

showing that canola oil is harmful to humans," he says.

I never use canola oil, largely because I have no reason to. For flavor, health, and cooking, I simply prefer other fats.

The flavor of canola oil is nothing special. Wild salmon and flaxseed oil are a far better source of omega-3 fats, and olive

and macadamia nut oil are more delicious sources of monounsaturated fats. For sauteing and roasting, I prefer to use olive

oil and butter, and for baking, butter or lard.

If you do use canola oil, recall the general rule for unsaturated fats: buy cold-pressed, unrefined oil and heat it gently,

never to the smoking point. If you would like to avoid genetically engineered rapeseed, look for certified organic oil.

The Abominable Egg White Omelet

AS LONG AS I CAN REMEMBER, my mother has eaten her breakfast in the late morning. When she comes in hungry from watering the

greenhouse, the squash pick, or any number of early morning jobs, breakfast is two eggs in butter, yolks runny, toast if the

bread box is full. I like eggs, too. Foolish me, I was nearly thirty years old before I resumed the habit of eating eggs for

breakfast.

The complex and delicate egg is indispensable. Fried, scrambled, poached, or baked in a frittata, eggs make a meal on their

own, and many wonderful dishes like mayonnaise and custard are impossible without them. But when the experts began to warn

about cholesterol, the egg— specifically, the yolk— became a guilty pleasure; hence the culinary and nutritional abomination

known as the egg white omelet. Eggs are rich in cholesterol, by the way, for the same reason breast milk is: cholesterol,

among many other uses, is an essential part of cell membranes in mammals. That fact, however, was not enough to save the egg.

In

Last Chance to Eat,

Gina Mallet writes of "the Egg Trauma."

In the early 1970s, out of the blue, the American Heart Association declared the egg a threat to the heart. The egg contained

278 milligrams of cholesterol, and food scientists had just decreed that no one should consume more than 300 milligrams of

cholesterol a day. The trauma that resulted lasted more than twenty years, almost crashed the egg industry, and turned what

was then the largest egg-eating country in the world against eggs. The attack would prove to be a classic case of food science

gone awry . . . I thought of course that the scientists, being scientists, had arrived at a safe level of dietary cholesterol

through proof. How wrong I was.

Curious about the fate of the egg, Mallet interviewed Donald J. McNamara, a biochemist and the executive director of the Egg

Nutrition Center, the egg industry lobby in Washington, D.C. She asked how scientists had arrived at the "safe" level of dietary

cholesterol. "Dr. McNamara laughed," Mallet writes. "That was disconcerting." In 1968 food scientists met to sort out a safe

amount of cholesterol to consume. Some were opposed to the very idea, while others firmly believed dietary cholesterol had

a significant effect on blood cholesterol, and after much haggling they reached a compromise. The average intake of cholesterol

was about 580 milligrams per liter of blood. Halving that, they settled on 300 milligrams— a political solution. "There's

not one bit of scientific evaluation in that number," McNamara told Mallet.

We've known for some time that eggs are actually good for your heart. A study of 118,000 people reported in the

Journal of

the American Medical Association

in 1999 was conclusive: "We found no evidence of an overall significant association between egg consumption" and heart disease.

In fact, people who ate five or six eggs a week had a

lower

risk of heart disease than those who ate less than one egg per week.

1

The researchers, led by Walter Willet at the Harvard School of Public Health, cited a host of reasons fresh eggs might prevent

heart disease: antioxidant carotenoids, vitamins, omega-3 fats, and good effects on blood sugar and insulin.

How did the egg get framed? Kudos to Gina Mallet for unearthing the origins of the arbitrary limit of 300 milligrams of cholesterol,

which sparked three decades of unjustified fear. Our understanding of cholesterol is also more sophisticated now. We know

that cholesterol metabolism— what the body

does

with LDL and HDL— is more important than the cholesterol in foods.

I was still curious about earlier studies apparently linking eggs and heart disease. Dr. Kilmer McCully, an expert on cholesterol

metabolism, told me that real eggs weren't to blame. The studies used dehydrated eggs, which are liquidized, pasteurized,

and spray-dried, in the same way powdered milk is made. Powdered eggs are mostly used in processed foods like cake mixes,

but unfortunately the label won't say

powdered eggs.

The cholesterol in powdered eggs (and powdered milk) is oxidized, which causes atherosclerosis. McCully says scientists have

known since the 1950s that eating oxidized cholesterol causes atherosclerosis, but natural cholesterol does not.

The home cook who favors industrial convenience foods can buy powdered eggs, which last five or ten years. Here's the pitch

from one company: "Our egg mix is mostly whole egg powder with a bit of powdered milk and vegetable oil . . . The egg mix

has been formulated to make scrambled eggs, omelets or French toast. We think you'll find our egg mix a labor-saving food."

No doubt, for some people, cracking open an egg is one chore too many, but I'm not sure you end up with more free time cooking

with powdered eggs— just more omega-6 fats you don't need and lots of oxidized cholesterol.

Fresh eggs, by contrast, are a nutritional bonanza. Above all, eggs are a fine source of inexpensive protein. In fact, because

the ratio of amino acids in eggs is so close to the ideal for human nutrition, eggs are the model for rating the quality of

protein in all foods. Compared to meat and fish, eggs keep well. A fresh egg (ideally unwashed, with its protective film intact)

will keep for two months in the fridge without much change in flavor or nutrition. An older egg will, however, be much easier

to peel. This information comes in handy if you like your deviled eggs to look perfect— or if you think the farmer is putting

you on about when they were laid.

A key ingredient in the egg yolk is lecithin, most famous as the emulsifier that makes mayonnaise creamy. Found in every human

cell, lecithin helps the body digest fat and cholesterol. Lecithin is the source of choline, a B vitamin-like agent vital

to the fetal brain. Eggs contain many antioxidants, including glutathione, which helps other antioxidants fight cancer and

prevents oxidation of LDL. Yolks are extremely rich in the antioxidant carotenes lutein and zeaxanthin, which are good for

the eyes (they prevent macular degeneration) and show promise in fighting colon cancer, and the lutein in eggs is more easily

absorbed than the lutein also found in spinach.

2

Along with liver, egg yolks have the highest concentrations of biotin— a B vitamin essential for healthy hair, skin, and nerves—

of any food. Biotin is vital for digestion of fat and protein. Vitaminlike betaine is also abundant in eggs and liver. Betaine

reduces homocysteine, an amino acid that causes atherosclerosis. All this makes chopped liver— the traditional Jewish paste

of liver (chicken or beef), eggs, and chicken fat— very nutritious. It's a pity that many modern recipes for chopped liver

call for corn oil instead of old-fashioned chicken fat, which is far better for you.

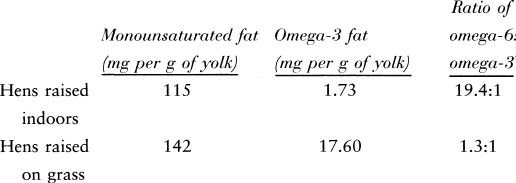

Eggs from pastured birds are superior to those from hens raised indoors, whose yolks are literally pale imitations of those

from hens on grass. Pastured yolks are a rich yellow from the beta-carotene in plants. They also contain more monounsaturated

fat, vitamins A and E, folic acid, lutein, and beta-carotene than indoor eggs. Pastured eggs are dramatically richer in omega-3

fats, which prevent obesity, diabetes, heart disease, and depression. The ratio of omega-6 to omega-3 fats in pastured eggs

is ideal (about 1:1), while an indoor egg has almost twenty times more omega-6 than omega-3 fats. The omega-3 fats come from

grass as well as insects, grubs, and worms. Another source is purslane, a lemony weed loved by poultry and foraging cooks

alike. Along with walnuts and flaxseed, succulent purslane is a rare plant source of the omega-3 fat ALA. Some egg farmers

feed flaxseed to indoor chickens to increase omega-3 fats.

WHY GRASS IS BEST: EGGS

* The ideal ratio is 1:1

Source: Artemis Simopoulos, "Omega-3 Fatty Acids in Health and Disease and in Growth and Development,"

American Journal of Clinical Nutrition,

Vol. 54 (1991): p.445.

Some eggs are advertised as "vegetarian." That may sound good, but it's actually not ideal. Recall that chickens are not natural

vegetarians. Omnivores like us, they need complete protein and thrive on a diet of grain plus plenty of insects, worms, grubs,

and other foods like sour milk. "Vegetarian" means the chickens were

not

fed cheap protein in the form of ground-up pigs, cattle, and poultry; that's good. But it also means something else. You may

be certain that a vegetarian chicken has never been outdoors. If it had, it might have eaten a bug or two. If you can't find

pastured eggs, barn-raised birds (not in cages) fed omega-3 are second-best.

The lesson of the egg trauma is simple. Don't eat factory eggs, powdered eggs, liquid eggs, pasteurized eggs, egg substitutes,

or any other kind of industrial egg product somebody invented in the laboratory. Do eat the real thing: fresh, whole eggs

from happy hens eating bugs and grubs outside on fresh green grass.

PEOPLE ARE BEWILDERED BY FATS, but that's nothing compared with the welter of myths, half-truths, fears, and health claims

around carbohydrates. Let me try to cut through the confusion. There are three macronutrients: protein, fat, and carbohydrate.

Fat and protein, as we've seen, are essential for life. But no carbohydrate is essential. The body uses carbohydrates for

energy, not structure or function, and it is theoretically possible to get all the energy you need from fat and protein. If

calories aren't required, a highly sensitive hormone called insulin ensures that surplus carbohydrate is stored (with impressive

efficiency) as fat— a little security against starvation in lean times. Because they don't cause insulin to rise quickly,

fat and protein are less likely to be stored. This is the gist of low-carbohydrate diets.

None of this means that carbohydrates per se are bad for you. Let's talk about weight first. I'm afraid my advice is not original:

eat as much carbohydrate as your body needs. How much that is depends on many things, including exercise and individual metabolism.

My mother used to say, "If you're out in the cold or you work hard at physical labor all day, you can eat a lot of bread and

rice." Some people gain weight easily on carbohydrates, while others can put away stacks of pancakes. A serving of pasta,

rice, polenta, or oatmeal about the size of your fist is probably right for most people. It's crazy to count grams of carbohydrates

in milk, carrots, or grapes. Even steak contains some carbohydrates. If you own a book listing those figures, throw it away.

That's a recipe for neurosis.

There are indeed "good" and "bad" carbohydrates. "Complex" carbohydrates in whole foods are good, and "simple" carbohydrates

like sugar are not. Eating sugar depletes B vitamins, which leads to premenstrual symptoms and depression, and promotes

Candida albi-cans,

a systemic yeast infection. Sugar also causes bone loss and, of course, tooth decay— but not for the reason you might think.

Sugar upsets the balance of calcium and phosphorus, which causes teeth to rot from the

inside

out. Remember what the dentist Weston Price found when he studied people eating traditional and industrial foods? Poor nutrition—

not lack of toothpaste— led to bone deformities and rotten teeth. Last but not least, by raising blood sugar, triglycerides,

and cholesterol, sugar leads to obesity, diabetes, and heart disease. Of all the industrial foods, sugar is the most villainous.

Complex carbohydrates such as whole wheat and brown rice naturally contain B vitamins, vitamin E, and fiber. But even these

complex carbohydrates are often refined. White or "polished" rice and white flour have been stripped of vitamins and fiber.

After they remove the best parts (the bran and germ), only the starch, or carbohydrate, remains. The food industry prefers

white flour because whole grain flour doesn't keep well; once grain is milled, wheat germ oil becomes rancid. White flour

is fortified with synthetic B vitamins, but the vitamins in whole foods are superior. By the way, the bran and vitamin E taken

from whole grains are fed to nutritionally deficient animals on factory farms. Animals on grass get all the fiber and vitamin

E they need.

WHAT'S IN A GRAIN?

A grain— the starchy seed head of a grass— has three parts.

Whole grain

means the food contains all three. White flour contains only the endosperm, or starch. Grainlike foods, such as buckwheat,

are often grouped with grains. They, too, are best whole.

•

Bran.

The hard protective coat; contains fiber, vitamins, and minerals.

•

Endosperm.

A complex carbohydrate wrapped in protein; the source of energy for a new plant.

•

Germ.

A tiny seed, capable of sprouting into a new plant; contains fat, protein, and vitamins.

The digestion of carbohydrate requires B vitamins. That's why the two nutrients are often found together in nature: whole

wheat, brown rice, and beets (a major source of sugar) all contain B vitamins. When you eat white flour, white rice, or sugar,

the body uses up B vitamins merely in the process of digestion. Thus, over time, refined carbohydrates deplete the body of

B vitamins.