Resident Readiness General Surgery (38 page)

Read Resident Readiness General Surgery Online

Authors: Debra Klamen,Brian George,Alden Harken,Debra Darosa

Tags: #Medical, #Surgery, #General, #Test Preparation & Review

AV nodal blockers are first-line therapy for supraventricular tachyarrhythmias.

COMPREHENSION QUESTIONS

1.

A 70-year-old patient arrives in the PACU following a peripheral vascular procedure. His blood pressure is 80/60 mm Hg, and you happen to glance at the monitor and note that, since leaving the OR, his heart rate has abruptly jumped to 160; he is diaphoretic and confused. Your therapeutic response depends on which of the following?

A. Past medical history

B. His current medical regimen

C. His hemodynamic status

D. His electrocardiogram

2.

A 60-year-old woman arrives in the PACU following a hysterectomy. She is stable on arrival but abruptly develops a tachycardia of 160 with a BP of 110/70. She “feels” her heart beating, but she is alert. Your therapeutic response depends on which of the following?

A. Past medical history

B. Her current medical regimen

C. Her hemodynamic status

D. Her electrocardiogram

Answers

1.

C

. When patients are hemodynamically unstable, your goal is to recognize and treat their cardiac rhythms—nothing else matters. Usually a rhythm strip or the

monitor is adequate for these purposes, and waiting for a formal EKG can needlessly delay treatment.

2.

D

. When a patient exhibits a tachydysrhythmia but is not symptomatic, you have time to determine whether the source of the problem is above or below the A-V node. If above (supraventricular), you have some pharmacologic options. A narrow complex QRS must derive from above the A-V node, and A-V nodal blockers should solve the problem. Remember, whenever in doubt (or just if you get frightened), you may always revert to cardioversion.

A 60-year-old Man in the PACU With New-onset PVCs

A 60-year-old Man in the PACU With New-onset PVCs

Alden H. Harken, MD

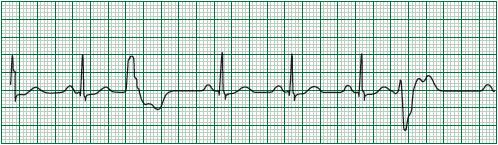

A 60-year-old male is admitted to the postanesthesia care unit (PACU) following an uneventful endovascular repair of an abdominal aortic aneurysm. On arrival, his BP is 140/90 and his heart rate is 110. Finger oximetry is 96%. He made 100 mL of urine during the previous hour. He is breathing comfortably with face mask oxygen. The nurse calls you because he is beginning to have a bunch of premature ventricular contractions (PVCs). When you arrive at the patient’s bedside, the nurse hands you a rhythm strip (see

Figure 29-1

):

Figure 29-1.

Rhythm strip which includes two wide complex beats that appear different (multifocal).

1.

Does this patient have a high or low risk of underlying cardiac disease?

2.

What is the first thing you should ask the nurse to do?

3.

Are the PVCs caused by a focal or diffuse myocardial process? How do you tell?

4.

What are five things you can do to help to prevent the arrhythmia from progressing to ventricular tachycardia?

5.

What is the therapy for a patient who progresses to ventricular tachycardia?

VENTRICULAR TACHYDYSRHYTHMIAS

Answers

1.

This is a patient with peripheral vascular disease and therefore likely coronary artery disease. He begins to throw multifocal (QRS morphology looks different) PVCs following a stressful, even if “uneventful,” vascular procedure. Therefore, when evaluating this patient, your index of suspicion for myocardial ischemia should be relatively higher.

2.

For any abnormal rhythm, your first step is to ask the nurse to obtain a 12-lead EKG to more fully characterize the rhythm, conduction, and repolarization of the myocardium. While you wait, you can begin by looking at the rhythm strip.

3.

When all the PVCs look the same (monomorphic), the culprit is typically a small bit of myocardium on the edge of a previous myocardial infarction. This bit of ischemic muscle did not die and has become electrically unstable. However, all the impulses activate the ventricles along the same pathway and all the PVCs look the same.

When the shapes (morphology) of the PVCs are different, the activation sites within the ventricles are also different, and something is making the whole myocardium electrically unstable/irritable.

This patient’s PVCs are polymorphic, and are therefore most likely related to a diffuse myocardial process.

4.

The rhythm strip exhibits classical multifocal ventricular ectopy (extra beats from several sites). Most beats are sinus (NSR) with a “narrow” QRS (0.08 second, 80 milliseconds or two little boxes on the ECG paper) following an atrial “P” wave. But then two PVCs appear, each with a unique morphology. Each of them takes at least five little boxes or 0.2 second to completely activate the ventricles. This is termed “aberrant ventricular conduction.” When an electrical impulse begins at the A-V node and travels down the high-velocity Purkinje fibers, the entire ventricles activate rapidly (0.08 second or a “narrow” QRS complex). When activation of the ventricles begins somewhere “ectopic” within the ventricular muscle, the impulse must travel along back dirt roads before it gets to the Purkinje superhighway. Activation of the ventricles takes a lot longer (“wide” QRS).

One worst case scenario would be that the PVCs become more frequent and ultimately progress to ventricular tachycardia. In order to reduce the chance of that happening, we target the five “usual suspects” for PVCs:

1.

Regional hypoxemia: If this is due to fixed coronary disease, there is not much you can do acutely. Otherwise, you can place the patient on face mask oxygen. This won’t hurt, and it might help.

2.

Hypokalemia: Make sure your patient’s serum potassium is above 4.0 mEq/L.

3.

Hypomagnesemia: Make sure your patient’s serum magnesium is above 2.0 mEq/L.

4.

Drugs: You can review the patient’s medications. The estimate is that about 15% of antiarrhythmic drugs actually function to promote arrhythmias. Digitoxicity classically provokes multifocal PVCs.

5.

Pain: Discomfort promotes secretion of endogenous catechols, which causes multifocal ectopy (PVCs). Be liberal with a morphine 2 to 4 mg IV bolus.

5.

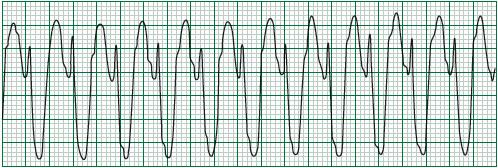

Even if you do everything correctly, there are some patients who will still progress to ventricular tachycardia (see

Figure 29-2

).

Figure 29-2.

Ventricular tachycardia.

Note the “wide morphology complex” ventricular activation. All these QRS complexes look the same because the most irritable ventricular site has taken over the cardiac rhythm.

The therapy is electrical cardioversion. Some patients in ventricular tachycardia still have sufficient cardiac output to remain awake and even normotensive. If your patient remains conscious, it is kind to pretreat with 20 mg of etomidate IV. When a patient goes into ventricular tachycardia or fibrillation, everyone typically gets pretty excited. You can probably convert most patients with lower-energy cardioversions, but it is best when the first shock successfully restores sinus rhythm. Few people will criticize you for cranking the cardioverter up to maximum (typically 150 J biphasic or 200 J monophasic). You should “synchronize” (sync) the shock for all but ventricular fibrillation. When you do sync the shock, you will need to depress the button for 4 to 5 seconds before the machine discharges—these 4 to 5 seconds are when the machine is trying to determine the rhythm. If you do convert ventricular tachycardia to ventricular fibrillation, just shock the patient again, this time with sync turned off because in this case there is no rhythm with which the machine can synchronize.

When you have successfully restored the sinus rhythm, it makes sense in most instances to load with amiodarone in the following manner:

1.

150 mg IV over 10 minutes

2.

Followed by 1 mg/min × 6 hours

3.

Followed by 0.5 mg/min × 18 hours

TIPS TO REMEMBER

PVCs result from electrically unstable ventricular myocardium.