Rise of the Robots: Technology and the Threat of a Jobless Future (8 page)

Read Rise of the Robots: Technology and the Threat of a Jobless Future Online

Authors: Martin Ford

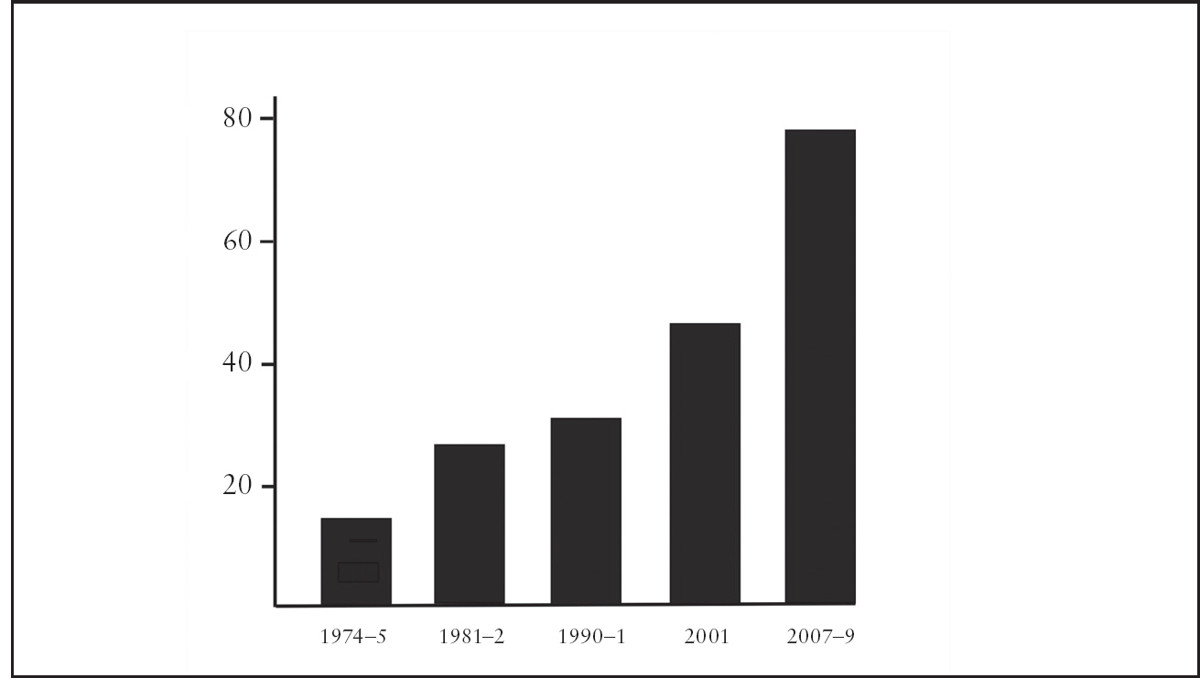

Corporate profits as a percentage of the total economy (GDP) also skyrocketed after the Great Recession (see

Figure 2.4

). Notice that despite the precipitous plunge in profits during the 2008–2009 economic crisis, the speed at which profitability recovered was unprecedented compared with previous recessions.

Figure 2.4. Corporate Profits as a Percentage of GDP

S

OURCE

: Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis (FRED).

21

The decline in labor’s share of national income is by no means limited to the United States. In a June 2013 research paper,

22

economists Loukas Karabarbounis and Brent Neiman, both of the University of Chicago’s Booth School of Business, analyzed data from fifty-six different countries and found that thirty-eight demonstrated a significant decline in labor’s share. In fact, the authors’ research showed that Japan, Canada, France, Italy, Germany, and China all had larger declines than the United States over a ten-year period. The decline in labor’s share in China—the country that most of us assume is hoovering up all the work—was especially precipitous, falling at three times the rate in the United States.

Karabarbounis and Neiman concluded that these global declines in labor’s share resulted from “efficiency gains in capital producing sectors, often attributed to advances in information technology and the computer age.”

23

The authors also noted that a stable labor share of income continues to be “a fundamental feature of macro-economic models.”

24

In other words, just as economists do not seem to have fully assimilated the implications of the circa-1973 divergence of productivity and wage growth, they are apparently still quite happy to build Bowley’s Law into the equations they use to model the economy.

Declining Labor Force Participation

A separate trend has been the decline in labor force participation. In the wake of the 2008–9 economic crisis, it was often the case that the unemployment rate fell not because large numbers of new jobs were being created, but because discouraged workers exited the workforce. Unlike the unemployment rate, which counts only those people actively seeking jobs, labor-force participation offers a graphic illustration that captures workers who have given up.

As

Figure 2.5

shows, the labor force participation rate rose sharply between 1970 and 1990 as women flooded into the workforce. The overall trend disguises the crucial fact that the percentage

of men in the labor force has been in consistent decline since 1950, falling from a high of about 86 percent to 70 percent as of 2013. The participation rate for women peaked at 60 percent in 2000; the overall labor force participation rate peaked at about 67 percent that same year.

26

Figure 2.5. Labor Force Participation Rate

S

OURCE

: US Bureau of Labor Statistics and Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis (FRED).

25

Labor force participation has been falling ever since, and although this is due in part to the retirement of the baby boom generation, and in part because younger workers are pursuing more education, those demographic trends do not fully explain the decline. The labor force participation rate for adults between the ages of twenty-five and fifty-four—those old enough to have completed college and even graduate school, yet too young to retire—has declined from about 84.5 percent in 2000 to just over 81 percent in 2013.

27

In other words, both the overall labor force participation rate and the participation rate for prime working-age adults have fallen by about three percentage points since 2000—and about half of that decline came before the onset of the 2008 financial crisis.

The decline in labor force participation has been accompanied by an explosion in applications for the Social Security disability program, which is intended to provide a safety net for workers who suffer debilitating injuries. Between 2000 and 2011, the number of applications more than doubled, from about 1.2 million per year to nearly 3 million per year.

28

As there is no evidence of an epidemic of workplace injuries beginning around the turn of the century, many analysts suspect that the disability program is being misused as a kind of last-resort—and permanent—unemployment insurance program. Given all this, it seems clear that something beyond simple demographics or cyclical economic factors is driving people out of the labor force.

Diminishing Job Creation, Lengthening Jobless Recoveries, and Soaring Long-Term Unemployment

Over the past half-century, the US economy has become progressively less effective at creating new jobs. Only the 1990s managed to—just barely—keep up with the previous decade’s job growth, and that was largely due to the technology boom that occurred in the second half of the decade. The recession that began in December 2007 and the ensuing financial crisis were a total disaster for job creation in the 2000s; the decade ended with virtually the same number of jobs that had existed in December 1999. Even before the Great Recession hit, however, the new century’s first decade was already on track to produce by far the worst percentage growth in employment since World War II.

As

Figure 2.6

shows, the number of jobs in the economy had increased by only about 5.8 percent through the end of 2007. Prorating that number for the entire decade suggests that, if the economic crisis had not occurred, the 2000s would likely have finished with a roughly 8 percent job creation rate—less than half of the percentage increase seen in the 1980s and ’90s.

That miserable job creation performance is especially disturbing in light of the fact that the economy needs to generate large numbers

of new jobs—between 75,000 and 150,000 per month, depending on one’s assumptions—just to keep up with population growth.

30

Even when the lower estimate is employed, the 2000s still resulted in a deficit of about 9 million jobs over the course of the decade.

Figure 2.6. US Job Creation by Decade

S

OURCE

: US Bureau of Labor Statistics and Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis (FRED).

29

Clear evidence also shows that when a recession knocks the wind out of the economy, it is taking longer and longer for the job market to recover. Temporary layoffs have given way to jobless recoveries. A 2010 research report by the Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland found that recent recessions have seen a dramatic decline in the rate at which unemployed workers are able to land new jobs. In other words, the problem is not that more jobs are being destroyed in downturns; it is that fewer are being created during recoveries. After the onset of the Great Recession in December 2007, the unemployment rate continued to rise for nearly two years, ultimately increasing by a full five percentage points and peaking at 10.1 percent. The Cleveland Fed’s analysis found that the increased difficulty faced by workers

finding new jobs accounted for over 95 percent of that 5 percent jump in the unemployment rate.

31

This, in turn, has led to a huge jump in the long-term unemployment rate, which peaked in 2010, when about 45 percent of workers had been out of work for more than six months.

32

Figure 2.7

shows the number of months it took for the labor market to recover from recent recessions. The Great Recession resulted in a monstrous jobless recovery; it took until May 2014—a full six and a half years after the start of the downturn—for employment to return to its pre-recession level.

Extended unemployment is a debilitating problem. Job skills erode over time; the risk that workers will become discouraged increases, and many employers seem to actively discriminate against the long-term unemployed, often refusing even to consider their résumés. Indeed, a field experiment conducted by Rand Ghayad, a PhD candidate in economics at Northeastern University, showed that a recently unemployed applicant with no industry experience was actually more likely to be called in for a job interview than someone with directly applicable experience who had been out of work for more than six months.

34

A separate report by the Urban Institute found that the long-term unemployed are not appreciably different from other workers, suggesting that becoming one of the long-term unemployed—and suffering the stigma that attaches to that category—may largely be a matter of bad luck.

35

If you happen to lose your job at an especially unfavorable time and then fail to find a new position before the dreaded six-month mark (a real possibility if the economy is in free fall), your prospects diminish dramatically from that point on—regardless of how qualified you may be.

Figure 2.7. US Recessions: Months for Employment to Recover (Measured from Start of Recession)

S

OURCE

: US Bureau of Labor Statistics and Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis (FRED).

33

Soaring Inequality

The divide between the rich and everyone else has been growing steadily since the 1970s. Between 1993 and 2010 over half of the increase in US national income went to households in the top 1 percent of the income distribution.

36

Since then, things have only gotten worse. In an analysis published in September 2013, economist Emmanuel Saez of the University of California, Berkeley, found that an astonishing 95 percent of total income gains during the years 2009 to 2012 were hoovered up by the wealthiest 1 percent.

37

Even as the Occupy Wall Street movement has faded from the scene, the evidence shows pretty clearly that income inequality in the United States is not just high—it may well be accelerating.