Salem Witch Judge (16 page)

Authors: Eve LaPlante

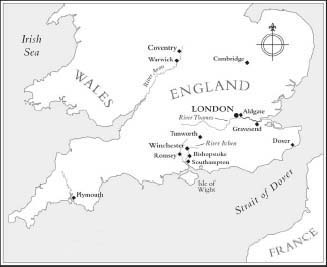

In contrast to London, most of England’s cities were small, with fewer than ten thousand residents. Most of the nation’s five million inhabitants lived in the countryside and grew their own food. Their average life span was less than forty years. Many women died in childbirth; one of every two children died before turning five. Bubonic plague, malaria, and leprosy were common. Few people traveled far from home. A boat was the most efficient mode of transport. Roads were poor and, in winter, often impassible. England was a highly stratified society in which nearly half the people lived at subsistence level. The gentry and nobility, who controlled most land and wealth, comprised less than 5 percent of the population. In the middle were yeomen—substantial farmers and tradesmen—and a small rising professional class of clergy, lawyers, merchants, and officials. While most people could not read or write, the percentage of Englishmen receiving higher education at Oxford, Cambridge, or the Inns of Court was greater—at 2.5 percent—than at any time until the twentieth century. Of the wide range of privileges in seventeenth-century England, the historian Keith Thomas has observed, “Not every under-developed society has its Shakespeare, Milton, Locke, Wren and Newton.”

Samuel had three goals for his stay in England: to see his kin and country of birth; to oversee his family property in Hampshire; and to assist Increase Mather in restoring colonial privileges. During his time in England he took in many familiar tourist sites. At the Tower of London he toured the fourteenth-century mint and the royal armory, admired the crown scepter, and noted the “lions [and] leopards” in the menagerie, which also housed giraffes, baboons, and even a polar bear in the moat. Samuel visited Parliament and took a barge up the Thames to Hampton Court Castle several times “to wait on the king,” with whom he hoped to discuss the protection of colonists’ rights. “We were dismissed sine die,” without having fixed another date to meet, he wrote on one such occasion, which was typical of his success. Samuel took the barge in the other direction to see the night sky from the observatory at Greenwich, where he spoke at length with John Flamsteed, England’s first Astronomer Royal. One particularly hot summer day Samuel dived into the great river “in my drawers” for

a “healthful and refreshing” swim, an activity he also enjoyed on sultry August afternoons in Boston’s Back Bay.

On a mid-March perambulation east of Aldgate in London he toured the Jews’ Burying Place at Mile End. Like many devout Puritans, Samuel had a special interest in Jews, not only because they were a covenanted people but also because their conversion to Christianity would be a sign that the end of the world was near. He and the grave keeper had a friendly chat over glasses of beer amid the graves. As Samuel prepared to leave he said to the man, “I wish we might meet in Heaven.”

“And drink a glass of beer together there,” the grave keeper replied.

Eager to see the places of his boyhood, Samuel hastened to Hampshire’s county town of Winchester—where Leonard Hoar’s mother-in-law, Bridget Lisle, had been beheaded—within a month of his arrival in London. At the Winchester market on February 19 Samuel purchased a bay horse, boots, a saddle and saddlecloth, a bridle, and other equipage, as a tourist today would rent a car.

Hampshire “has always been an open gate for English discovery and enterprise towards the west,” according to Nathan Chamberlain. “The sun is warmer there than in the North Land, and its gardens and orchards fuller.” Cattle, ponies, pigs, donkeys, and deer still roam its forests, heaths, and lowland moors. Winchester was once England’s capital, and it is still heart of Hampshire County. Better preserved than many English towns, Winchester retains a medieval feel on account of its surrounding Roman wall, narrow cobbled streets, thirteenth-century castle, magnificent Gothic cathedral, and few modern high-rises. The town straddles the Itchen River, which is crossed by stone bridges.

Nestled near the river is the campus of Winchester College, a secondary school for clever boys. The school’s ancient barrier wall and dark Gothic buildings seem to say to the world, “Keep out.” Winchester College is fifty years older than Eton. It was founded in the late fourteenth century by William of Wykeham, bishop of Winchester and chancellor to Richard II, to educate seventy “poor and needy scholars.” William of Wykeham, who also founded New College, Oxford, supervised the creation of the medieval campus, which

still stands beside a meadow dotted with eighteenth-century plane trees.

Samuel visited Winchester College on February 25 and requested a tour. A man led him through a cloister to “the chapel on the green,” an architectural oddity existing nowhere else in the world. A chantry, a medieval structure in which monks chanted for the dead, was set in the middle of a cloister, surrounded by grass. Samuel entered the chantry and followed the man up a spiral of marble stairs to the “library around the stairs,” a large room with timber beams, white plaster walls, and delicately mullioned Gothic windows.

In this light-filled medieval chamber, Samuel encountered a remarkable collection of books, which William of Wykeham had begun in the fourteenth century. Samuel saw Peter Comestor’s Historia Scholastica, from around 1175, and a four-volume vellum songbook published in 1564 and inscribed by a suitor to Queen Elizabeth I. An early-thirteenth-century manuscript, Life of St. Thomas Becket, possibly by William of Canterbury, contained the earliest known portrait of Becket. In Ranulf Higden’s 1380 work, Polychronicon, the librarian showed Samuel a remarkable oval map of the world that places Jerusalem at the center and Paradise, in the east, at the top. Samuel admired several books donated in 1600 by Sir Robert Cecil, secretary of state and treasurer to King James I, including a 1587 Heidelberg Bible and many works of Luther, Zwingli, and Calvin.

Startled by the quality of this collection, Samuel decided on the spot to leave his Indian Bible here. “Samuel Sewall, like modern donors, may have been animated by the idea of being remembered in a library that has one of the longest continuous histories in the Anglo-Saxon world,” a later keeper of the Winchester College library conjectured. Beyond that, Samuel had a personal reason for wanting to leave his Indian Bible at Winchester College. His alternative English life—the life he’d have lived had he not sailed to America in 1661—might have continued at Winchester College, which then admitted scholars as young as ten years old. Doubtless aware of this, he handed his Indian Bible to the college librarian, confident that this precious token of the delights and possibilities of the New World had found its home in the old.

The text of Samuel’s Indian Bible, which is now the most valuable object in the collection at Winchester College, begins:

Negonne Oosukkuhwhonk Moses, ne asoweetamuk

GENESIS

Chap I

1. Weske kutchinik ayum God kusuk kah Ohke.

2. Kah Ohke mo matta kuhkenauunneunkquttinnoo kah monteagunninuo, kah pohkenum woskeche moonoi, kah Nashauanit popomshau woikeche nippekontu.

3. Onk noowau God wequi, kah mo wequai.

4. Kah wunnaumum God wequai neen wunnegen; kah wutchadchanbeponumun God noeu wequai kah noeu pohkenum.

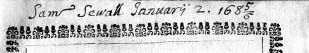

The words INDIAN BIBLE appear in gold leaf on the spine. One of its two original clasps is missing. Below the Algonquian title, MAMUSSE WUNNEETUPANATAMWE UP-BIBLUM GOD, are the words “John Eliot, Cambridge. Published by Samuel Green, printer, MDCLXXXV, second edition, Boston.” Atop the title page, in his confident hand, Samuel penned his name and the date he received the book from the printer: “Sam. Sewall January 2, 1685/6”—January 12, 1686, by modern reckoning—which was three years before he deposited it at Winchester College. The Bible is stored in a locked vault and displayed once every five years. It has never left Winchester College.

In the months following Samuel’s tour of the college, he visited his boyhood villages and towns. He saw many cousins in the village of Baddesley (pronounced “Bad-ess-ly”), where he had spent several years in the 1650s. At Baddesley’s medieval parish church he stood before the grave of his Aunt Rider, who had died in 1688. He walked to nearby Lee, a village of about a dozen thatched houses, to see his father’s land and farmhouse, which still produced a modest income, twenty pounds a year.

During the few years that his parents had spent in Puritan England, they possessed the means to move several times. While there is no record of Henry Sewall’s schooling, his status as a cattle farmer who occasionally preached indicates education and material comfort. Given the tendencies of Puritan boys of his background, Henry had likely attended English grammar schools before coming to America at nineteen, in 1634. He and his wife lived first in Warwick, northwest of London, near Coventry, where Henry’s grandfather, a wealthy linen draper, had been mayor. To be closer to Jane’s family, the Dummers, Henry and Jane Sewall moved south to Hampshire. By May of 1649, when she delivered their first child, Hannah, they were in the village of Tunworth. Before their second child was born they moved again, to the village of Bishopstoke, which lies between Winchester and Southampton.

The Sewall house in Bishopstoke, which probably still stood when Samuel visited this ancient parish in 1689, was a hundred or so yards northeast of the Bishopstoke church. On the rising ground east of the River Itchen, it was one of forty or fifty similar abodes—seventy hearths, according to a 1665 census survey—whose occupants were farmers and millers. The sort of thatched house still common in rural England, it was timber framed and coated with wattle and daub, a mixture of the hair of a horse, goat, or cow; lime; and mud plaster. It had a brick-lined chimney and one or two fireplaces. A parlor and spacious kitchen with a long table and benches occupied the ground floor.

In a bedchamber on the second floor of this house, a little before daybreak on Sunday, March 28, 1652, Samuel Sewall had been born. “The light of the Lord’s Day was the first light that my eyes saw,” he wrote decades later of his origins. Samuel was, or hoped to be, with God from the start.

Five weeks later, on May 4, 1652, Henry and Jane carried their new son to the parish church, set on a knoll on the eastern bank of the River Itchen. Swans swam amid the bulrushes in the river. A mill stream lapped against the churchyard. The church, which appears in the 1086 Domesday Book, a survey of English land and landholders, stood until 1891, serving for most of that time as the physical and social center of the village. Medieval paintings of biblical scenes decorated its interior walls. On that May morning in 1652, a Cambridge-

educated Puritan minister named Thomas Rashly preached a sermon before baptizing the Sewalls’ baby. Henry held up his first son and named him Samuel, after the Old Testament leader who judged Israel and “built an altar unto the Lord.” Following the service the Reverend Rashly and many other family and friends of Henry and Jane crowded into the Sewall house for “an entertainment” in honor of the new baby.

Before Samuel was two the family moved to the neighboring village of Baddesley, where three younger siblings were born and baptized, John in October 1654, Stephen in August 1657, and Jane in October 1659. Baddesley is also mentioned in the Domesday Book. It consisted of a medieval church, in whose yard Samuel’s Aunt Rider lies, and a nearby common surrounded by thatched farmhouses. Baddesley was even smaller than Bishopstoke, with fewer than forty houses (fifty-six hearths in the 1665 census). Samuel’s lengthy education began here: at “Baddesley, by the merciful goodness of God, I was taught to read English” and to write. At age five or six Samuel began a daily four-mile walk from Baddesley to the market town of Romsey, which was dominated by a monumental twelfth-century Norman abbey that survived King Henry VIII’s dissolution of the monasteries only because a clever Benedictine abbot sold it to the townspeople in 1544, transforming it into a parish church. Samuel’s daily route to school went from the South Baddesley Church across Baddesley Common through a forest to Romsey Common fields, where cattle grazed.

Samuel’s grammar school was called the Romsey Free School even though the boys’ parents paid tuition. Located on the abbey grounds, it may have been inside the abbey, according to a local historian, Phoebe Merrick. Graffiti initials around a window high on the nave’s northwestern wall are considered the work of schoolboys in the seventeenth century, when a schoolroom sat within the nave on an upper floor that no longer exists. The schoolmaster, whom Samuel remembered fondly, was Mr. Figes (“Fid-ges”). By the 1680s, when Samuel visited as an adult, the boys at the Romsey Free School wore a uniform of “blue coats, puckered, no pockets” and a flat cap with a white tassel and band.