Salem Witch Judge (18 page)

Authors: Eve LaPlante

In 1690, in the wake of Indian attacks on Maine, the Massachusetts General Court swore in Phips as major general of the provincial army. Samuel was present at the Town House that March day. He observed “eight companies and troops” training and joined his own South Company in prayer at the Common. Three days later, on March 25, 1690, “Drums beat through the town for volunteers.”

Increasing attacks by French and Indians prompted New York’s acting governor, Jacob Leisler, to demand that Massachusetts send two “commissioners” to New York for a joint colonial conference on “common safety.” Samuel Sewall and William Stoughton volunteered for the trip. They set out on horseback on April 21, each waited on by several attendants. They left their horses (but not their bridles and saddles) in Newport, Rhode Island, and paid a sloop’s captain to take them across the sound to Oyster Bay, Long Island. On rented horses they rode to Jamaica, in modern-day Queens, Brooklyn, and by ferry to Manhattan. Samuel was not sanguine about Leisler’s public safety meeting, which “brought great heaviness on my spirit.” Yet he relished the chance to learn to sing a psalm in the Dutch language while visiting a Dutch Reformed church. It was Psalm 25: “Unto thee, O Lord, do I lift up my soul…. Let me not be ashamed, let not mine enemies triumph over me….” This seemed “extraordinarily fitted for me in my present distresses, and by which [I] have received comfort.”

That month Major General William Phips led more than seven hundred soldiers in eight small ships north to Port Royal, Nova Scotia. Meeting little resistance, he seized the town on May 11. Samuel, who had contributed a hundred pounds to the expedition, wrote on May 22, “We hear of the taking [of] Port Royal by Sir William Phips…which somewhat abates our sorrow for the loss of Casco” in Maine.

French and Indian forces had continued to attack towns along the New England coast. They hit the coastal village of Saco, Maine, on April 21, killing people and animals, taking human hostages, and

burning houses. Four days later they routed Cape Porpoise. A group of Madockawando Indians and French soldiers burned the English settlement of Falmouth near modern-day Portland, Maine, on May 20, killing some people and capturing others. A month later they raided Cocheco, across the river from Salmon Falls, at the Maine–New Hampshire border. They seized the English fort at Pemaquid in Maine, raided Sagadahoc, and headed south through North Yarmouth, Black Point, Saco, and Oyster River. The latter, now the town of Durham, New Hampshire, is hardly thirty miles from Boston’s North Shore. With a sense of growing fear, the Massachusetts court dispatched two councillors, John Hathorne and Jonathan Corwin, to investigate in Maine and New Hampshire. Hathorne and Corwin recommended sending more troops and supplies to Maine garrisons and warning frontier settlers not to be “surprised by the enemy and suddenly destroyed as other places have been.”

These many battles were the start of King William’s War, the first of a series of battles now collectively known as the French and Indian Wars. These battles between Britain and France over their colonies would last more than seventy years, into the second half of the eighteenth century. King William’s War, which was fought on American and European soil between 1689 and 1697, was ultimately pointless: the September 1697 Treaty of Ryswick, which ended it, restored all colonial possessions to their prewar status, as if no war had been fought.

But to the French, Indian, and English people who lost friends and family in King William’s War, it felt as devastating as King Philip’s War almost twenty years earlier. For Samuel, a member of the governing council who supported the war with hundreds of pounds of his own money and feared every day for his community’s safety, the war was another blow to the New England way.

In the midst of this chaos, on May 19, 1690, John Eliot, the Indian Apostle, died at eighty-six. “This puts our election [next week] into mourning.” More bad news followed. In July Samuel was “alarmed” to hear “of Frenchmen being landed at Cape Cod, and marched within ten miles of Eastham.” Meanwhile his brother Stephen and a hundred fifty other local volunteers sailed to Canada. Samuel prayed, “The good Lord of hosts go along with them.” Smallpox spread through

Boston, prompting a quarantine. On July 25, when Nathaniel Saltonstall, one of the magistrates, tried to come to town to discuss the war with his colleagues on the court, he was not allowed to cross the river from Charlestown. Samuel and Wait Still Winthrop took the ferry to Charlestown to converse with Saltonstall there. A fire in early August destroyed fourteen houses and many warehouses along the docks in the North End.

On August 8 Samuel rode his horse to Nantasket, a peninsula south of Shawmut, to watch thirty-two ships and two thousand English soldiers gather in the harbor in preparation for Phips’s second expedition to Canada. Following his great success at Port Royal, Major General Phips planned to attack the stronghold of Quebec. Samuel watched as a “Lieutenant General muster[ed] his soldiers on George’s Island.” As a magistrate, Samuel was invited on board a warship, which sailed him and other notables “up to town.” Late that night in Boston, he and Wait Still Winthrop and two other men ceremoniously rolled two-wheeled “carriages for field-pieces” such as cannons down to the dock for delivery to warships anchored at Nantasket.

The following day Samuel rode south to Hull, near Nantasket, to dine with “Sir William [Phips] and his Lady” as the major general waited for the wind to “spring up.” Phips would have preferred to delay his trip further—he had not secured a pilot for the mission and was short on supplies and ammunition—but the coming winter urged him on. At about six that evening, Samuel noted, the “wind veered and the fleet came to sail. Four ships of war and twenty-eight” other ships left Boston harbor, headed up the coast to the mouth of the Saint Lawrence River.

Samuel gallantly “carried” Lady Mary Phips home to Boston that evening on his horse or, more likely, in her coach. En route they stopped briefly in Braintree to see Samuel’s wife’s cousin Daniel Quincy, who was extremely ill. Continuing on, he left Lady Mary in Boston’s North End at her brick mansion, which was nearly as large as the nave of the North Church. The Phipses lived on Charter Street, around the corner from Increase and Mary Cotton Mather’s house at the site of Caffé Vittoria on modern-day Hanover Street.

The next day, during the service at the Third Church, a rider came from Braintree to tell Samuel that Daniel Quincy was close to death.

Daniel, the oldest son of Judith Hull’s brother Edmund and Joanna Hoar Quincy, was a silversmith who worked with John Hull. Samuel slipped out of the church and galloped to Braintree. “Cousin Quincy” was surrounded by family, including his wife and his Aunt Judith, Samuel’s mother-in-law. Samuel prayed and read psalms at the bedside. He sent for the Reverend Willard, who arrived with more prayers. As Samuel watched Daniel, who was only thirty-nine, pass from this life, he prayed silently, “The Lord fit me for my change and help me to wait till it come.” The family laid Daniel’s body in John Hull’s tomb in Boston two days later. Samuel led the widow, Ann, followed by the children, who included one-year-old John Quincy—grandfather of Abigail Quincy Adams and great-grandfather of John Quincy Adams, sixth president of the United States—and many relatives and friends.

Hannah Sewall, who was about eight months pregnant, took ill during Cousin Quincy’s funeral. “She had a great flux of blood, which amazed us both,” Samuel reported. He hurried her home and called for a nurse and the midwife, Elizabeth Weeden. That night he prayed for hours, fearing the worst.

The next morning his wife was still alive and they had a new baby girl, born before dawn. At Sabbath service on August 24 the Reverend Willard baptized her and six other babies. Samuel’s new daughter “cried not at all, though a pretty deal of water was poured on her by Mr. Willard.” Samuel named her Judith, “for the sake of her grandmother and great grandmother, who both bore that name.” During the service he prayed inwardly to be a better Christian: “Lord, grant that I who have thus solemnly and frequently named the name of the Lord Jesus may depart from iniquity.” He asked God “that mine”—his children—“may be more Yours than mine, or their own.”

Two months later the new baby was dead. On the evening of September 20, inexplicably, “my little Judith languishes and moans, ready to die.” Samuel rose from his bed at two in the morning to “read some psalms and pray with her.” The Reverend Willard, who had buried one of his own children just three days earlier, arrived before eight in the morning to pray. The vigil at the Sewall house lasted until baby Judith died just before eight that night. “I hope [she] sleeps in Jesus,” Samuel said.

Solomon Rainsford carefully steadied her little coffin while setting it in the family tomb on September 23. Mourners included Wait Still Winthrop, John Richards, the Bradstreets, the Willards, the Moodys, Increase Mather and his wife, and three generations of Samuel’s family.

Alone at home, Samuel wondered what God was saying to him. In five years he had buried four of his last five babies. So many deaths intensified his sense of unworthiness. He felt impotent in the face of medical conditions that were not yet identified or understood. Typical of his peers, according to the historian Keith Thomas, Samuel had “no satisfactory contemporary explanation for the sudden deaths which are today ascribed to stroke or heart disease,” viral or bacterial infections, tuberculosis, convulsions, or cancer. Lacking a germ theory of disease—which would not be established until the mid-nineteenth century with the work of scientists such as Louis Pasteur—people considered most sickness inexplicable. They presumed that God or other supernatural forces were agents of disease and death.

October brought more bad news. Sir William Phips’s second military expedition to Canada ended in disaster. The expedition had been planned the previous spring as part of a wide attack on the French in Canada and their Indian allies. To divert the French, Iroquois and English forces from New York and Connecticut headed to Montreal. A separate English expedition aimed to threaten Indians “at the East,” in Maine. Meanwhile, Phips’s massive force was to surprise Quebec. To Samuel’s dismay, though, both the Montreal and Maine attacks stalled. Phips reached Quebec in early October but lost his courage and delayed his attack. The French, under Louis de Baude, Comte de Palluau et de Frontenac, forced back the English and killed an estimated two hundred soldiers. Numerous English ships were lost on the St. Lawrence River.

This disaster bred others. Massachusetts’s treasury, which had borrowed fifty thousand pounds to fund this expedition, was empty. The New England economy would suffer for twenty years. Currency was devalued. Foreign trade declined dramatically, in part because of the war with the French. Some prominent Bostonians blamed Phips. Samuel defended him in a letter he sent to Increase Mather in London in December 1690. “You will hear various [negative] reports

of Sir William Phips…. I have discoursed with all sorts, and find that neither activity nor courage were wanting in him [at Quebec], and the form of the attack was agreed on by the Council of War” in Boston. In this instance Samuel felt comfortable sharing the blame for the disaster.

Despite all the world’s upheaval, God still blessed him and Hannah. Within a few months she was again pregnant. Samuel began arranging to build a large addition to their house. Early in 1692 he consulted with his minister, asking “whether the [difficult] times would allow one to build an” addition. Encouragingly, the Reverend Willard replied, “I wonder you have contented yourselves so long without one.” Only later did Samuel realize that while he was discussing his house renovations with Willard, French and Indian warriors were destroying the entire English settlement at York in Maine. Ashamed, Samuel admitted, “I little thought what was acted that day at York.”

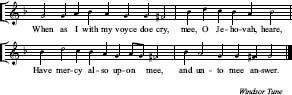

Worldly matters would continue to interfere with his renovation plans. Not until January 1694 would he finally stick a pin, for good luck, into the frame of the addition, which contained several large chambers and a new kitchen. Construction was not complete until the summer of 1695, when Samuel gathered several ministers for a private fast in “our new chamber. Mr. Willard begins with prayer, and preaches,” and the Reverends James Allen and John Bailey prayed too. Together the group sang part of Psalm 27, chosen by Samuel.

7 When as I with my voyce doe cry,

mee, O Jehovah, heare,

Have mercy also upon mee,

and unto mee answer.

8 When thou didst say, seek yee my face,

my heart sayd unto thee,

thy countenance, O Jehovah

it shall be sought by mee.

9 Hide not thy face from mee, nor off

in wrath thy servant cast:

God of my health, leave, leave not mee,

my helper been thou hast.

10 My father & my mother both

though they doe mee forsake,

yet will Jehovah gathering

unto himself me take.

11 Jehovah, teach thou mee the way,

and be a guide to mee

in righteous path, because of them

that mine observers bee.