Salem Witch Judge (14 page)

Authors: Eve LaPlante

Schoolchildren learn that the Puritans came to America for religious freedom, but the truth is more complex. The Englishmen who settled America had aims both spiritual and secular. Magistrates and ministers both collected land. Some of Samuel’s Muddy River acreage had once been John Cotton’s farm, a gift from the ruling court to the politic First Church minister. The records of land tracts granted by the magistrates of the Great and General Court to themselves and their allies show the roots of real estate speculation in America.

Over the years Samuel, like his and Hannah’s male forebears, expanded his family’s real estate. “The care and sale of [land] took much of his business time and energy,” Nathan Chamberlain noted. In 1687, in imitation of the leading men of the first generation, Samuel purchased most of an island in Boston Harbor. That May eight men witnessed “my taking livery and seisin of [nearly five hundred acres of Hog] Island by turf and twig and the house,” along with seven oxen and steers, eight cows, one hundred sixty sheep, thirteen swine, two horses, one mare, “four stocks of bees,” some fowl, and a sailboat with oars and a fishing rod. A tenant farmer occupied the island, which Samuel used for family picnics and for grazing sheep and cattle. He built a wharf there and planted many trees. Sometimes he spent the night on the island under the stars.

In the summer of 1688 Edmund Andros, the provincial leader, would try to unsettle Samuel’s claim to the island. “There is a writ out against me for Hog Island,” Samuel noted that July, “and against several others…as being violent intruders into the king’s possession.” Samuel fought back and maintained his deed. An excellent judge of real estate, horses, and people, Samuel was not afraid to say his mind. Ten years after lending a man from Barbados ten pounds, he wrote to him in 1700, “Sir, I presume the old verity ‘If knocking thrice, no one comes, go off ’ is not to be understood of creditors in demanding their

just debts. The tenth year is now current since I let you ten pounds, merely out of respect to you as a stranger and scholar…. I am come again to knock at your door to enquire if any ingenuity or honor dwell there….” He advised an agent of his on Barbados, “Recover the money and remit it to Mr. John Ive, merchant in London, for my account.”

At home, though, Samuel sometimes had to bite his tongue. John Hull was master of the house as long as he lived, which would be seven years after Samuel joined the family. The two men shared a deep respect, yet conflicts occasionally arose. One evening in February 1677 the two men were talking together in the parlor before a fire. Hull mentioned his irritation that someone in the colonial treasury, which he ran as treasurer, had allowed a man to pay his taxes in oats. Samuel threw some logs on the hearth. To Samuel’s amazement, his father-in-law lashed out at him for wasting wood. “If you should be so foolish,” Samuel later quoted his father-in-law as saying, “then I should have no confidence in you, for your mind would be as unstable as the wind.”

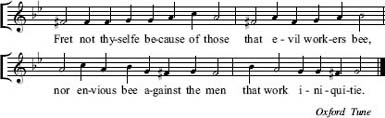

Samuel knew that Hull’s anger was misdirected, but he still felt hurt. Saying nothing, he retreated to his bedchamber to console himself with Scripture. He found reassurance in 1 Peter 1: 6, “Wherein ye greatly rejoice, though now for a season, if need be, ye are in heaviness through manifold temptations.” This reminded Samuel that “no godly man hath any more afflictions than what he hath need of.” Singing several verses of Psalm 37, which reassures those who “fret” because of evil that the wicked shall soon die, further improved his mood.

Fret not thyselfe because of those

that evill workers bee,

nor envious bee against the men

that work iniquitie.

2 For like unto the grasse they shall

be cut downe, suddenly:

and like unto the tender herb

they withering shall dye.

3 Upon the Lord put thou thy trust,

and bee thou doing good,

so shalt thou dwell within the land,

and sure thou shalt have food.

4 See that thou set thy hearts delight

also upon the Lord,

and the desyres of thy heart

to thee he will afford.

5 Trust in the Lord: & hee’l it work,

to him commit thy way.

6 As light thy justice hee’l bring forth,

thy judgement as noone day.

7 Rest in Jehovah, & for him

with patience doe thou stay:

fret not thy selfe because of him

who prospers in his way,

Nor at the man, who brings to passe

the crafts he doth devise.

8 Cease ire, & wrath leave: to doe ill

thy selfe fret in no wise.

9 For evil doers shall be made

by cutting downe to fall:

but those that wayt upon the Lord,

the land inherit shall.

Inspired by his father-in-law’s land acquisition, Samuel developed a concern for his parents’ properties in England. In 1677 he wrote to Stephen Dummer, a maternal uncle in Hampshire, England, asking him to “take care of my father’s lands, especially at Lee, writing down all his receipts and payments.” Two years later the Boston selectmen made Samuel a perambulator of Muddy River, Roxbury, and Cambridge. Perambulators met regularly to walk around grazing lands to

ensure public order, land claims, and property boundaries. Samuel discharged this responsibility once a month in good weather, “chiefly,” he admitted in June 1687, “that I may know my own” land, which “lies in so many nooks and corners.”

The extent of Samuel’s holdings in Muddy River are no longer known. The twenty-five acres granted to Hannah’s grandfather in 1636 had expanded through further purchases by John Hull to more than three hundred acres that extended east to the Muddy and Charles Rivers and northwest to the Cambridge line. This land was tillable southeast to the old Cedar Swamp, now known as Hall’s Pond. Sewall’s farm, as the growing parcel was called by the 1680s, included much of modern-day Coolidge Corner and Brookline Village. Samuel called his farm Brooklin—short for Brook-lying—in honor of the waterway marking its northern border, a tributary of the Charles River known as the Smelt Brook. Years later, when residents of this region, then called Muddy River, voted to incorporate themselves as a town, they named the new town Brookline, after Sewall’s farm.

Samuel rode to Muddy River on March 16, 1686, to survey land and “adjust the matter of fencing” between Thomas Danforth, a former deputy governor, and his neighbor Simon Gates. Muddy River, a “rolling landscape of some picturesqueness,” according to a historian, served as Boston’s “back cow pasture.” Since the 1630s, by court order, all barren cattle, weaned calves, and swine more than three months old were removed from the Shawmut Peninsula to save its house gardens. The village of Muddy River, situated two miles west of the town, had “good ground, large timber, and stores of marshland” and meadow, and fewer than a hundred English and Indian inhabitants.

Samuel met Danforth and Gates alongside the Muddy River (another tributary of the Charles) at a creek near the juncture of the towns of Boston, Roxbury, and Cambridge. The three men agreed to measure a line “from a stake by the creek 16 rods [of] marsh” upland to “a little above the dam” and “about a rod below an elm growing to the Boston-side of the fence.” The deputy governor would “fence thence upward above the dam” and Gates would “fence downwards to the stake by the creek where by consent we began.” After noon the men dined at Gates’s farmhouse. Dinner, the main meal of the day, was

usually a meat stew or pottage (commonly beef, deer, hare, squirrel, pigeon, turkey, or pheasant) and root vegetables such as parsnips, carrots, turnips, and onions. Desserts were apples, peaches, berries with milk and sugar, and yokeage, a mix of parched, pulverized Indian corn and sugar borrowed from Native American cuisine. Breakfast and supper consisted of oatmeal or cornmeal mush mixed with milk or molasses. Most meals were accompanied by beer and hard cider, according to the historian Keith Thomas: “Beer was a basic ingredient in everyone’s diet, children as well as adults…. Each member of the [seventeenth-century English] population, man, woman, and child, consumed almost forty gallons a year,” or nearly a pint of beer a day. Water was often unclean and not potable, so people drank alcohol. The food at Gates’s pleased Samuel, as did Danforth’s offer to let the Gates family “go on foot to Cambridge Church directly through his ground.” Such courtesies could arise only when men of property felt their claims of ownership were respected, especially now that all claims were in question due to the loss of the charter.

Arriving home from his farm that day, Samuel learned that smallpox was again in Boston. The previous November an acquaintance had succumbed to the virus. Samuel himself almost perished from smallpox at twenty-six, two years after his wedding and not long after his firstborn died. Bedridden for six weeks in the autumn of 1678, “I was reported to be dead…. But it pleased God of his mercy to recover me. Multitudes” in Boston died then, including John Noyes and Benjamin Thirston, “two of my special friends.”

Despite Samuel’s many anxieties, some news was simply good. He learned in the late spring of 1686 that Hannah, now twenty-six, was pregnant for the seventh time in ten years. The new baby, another boy, arrived on January 30, 1687. At his baptism, by the Reverend Willard at the next Sabbath day, “the child shrunk at the water but cried not.” Eight-year-old Sam Jr. “showed the midwife” Elizabeth Weeden, who carried in the infant, “the way to the pew.” Samuel held up his new son and named him Stephen, after his own brother. Stephen seemed healthy. He suffered no convulsions. He cut two teeth in June, when he was five months old. A month later, though, he was “very sick.”

Samuel called on the Reverend Willard. The minister and his wife came to the house to pray with the baby on the evening of Monday,

July 25, and again the next morning. Tuesday afternoon, in his grandmother’s bedchamber, as Nurse Hill rocked him in her arms, Samuel and Hannah’s “dear son Stephen Sewall” expired.

The family rushed to burial on account of the summer heat. Early Wednesday evening four young boys close to the family bore little Stephen’s coffin from the Third Church to the graveyard. As usual, the family walked two by two. Samuel led his wife. His brother Stephen led the grandmother Judith Hull. Sam Jr., nine, led his sister Hannah, seven. “Billy Dummer,” a ten-year-old cousin who would become Massachusetts’s governor in 1723, led Samuel’s five-year-old daughter, Betty. “Cousins” Quincy and Savage and many other mourners followed, in pairs.

Samuel asked two strong men, Samuel Clark and Solomon Rainsford, to carry Stephen’s coffin inside the tomb. While descending the steps into the burial chamber, Rainsford slipped on a loose brick and dropped his end of the coffin. It landed on Samuel’s firstborn “John’s stone,” which was “set there to show the entrance.” Samuel, who missed nothing, felt relief that Clark “held his part steadily” and so the crowd heard “only a little knock.”

After the short ceremony, as people drifted away, Sam Jr. turned back to peer into his family tomb. He saw “a great coffin” inside, that of his grandfather John Hull, which terrified him. Later, in his diary, Samuel noted his compassion for his son. His deep faith in salvation through Christ did not always prevail over his anxiety about death. While away from home in 1689 he woke from a nightmare in which his wife, Hannah, was dead, “which made me very heavy.” Six years later he dreamed that all but one of “my children were dead,” which “did distress me sorely.” Ten years after that, in 1705, he had a “very sad dream” in which “I,” like a felon, “was condemned and to be executed.” He too was afraid.

Sam Jr. cried all the way home from his baby brother’s funeral. His sisters, Hannah and Betty, burst into tears. Their parents and servants “could hardly quiet them” at the mourners’ feast. A few days later Samuel’s brother Stephen came to visit. He said the French had seized two ships from Salem, including one in which Stephen had invested. The ship’s “whole fare [was] due to him,” Samuel noted, “so that his livelihood is in a manner taken away. Here is wave upon wave” of bad news.

Consolation following desolation, Hannah conceived another child in November 1687. She gave birth to a son on August 15, 1688. Samuel and Hannah now had four living children and four children who had died. On August 19 Samuel carried the new baby to the Third Church, where the Reverend Willard preached a sermon before baptizing him. Samuel named this son Joseph “not out of respect to any relation” but for the “first Joseph,” Jacob’s beloved son, and “in hopes of the accomplishment of the prophecy, Ezekiel 37 and such like.” In this Old Testament passage the Lord says, “Behold, I will take the stick of Joseph, which [is] in the hand of Ephraim, and the tribes of Israel…and make them one stick…. I will take the children of Israel from among the heathen,…I will make them one nation in the land upon the mountains of Israel…. I will save them out of all their dwelling places, wherein they have sinned, and will cleanse them: so shall they be my people, and I will be their God.”

Samuel, who could already see that Sam Jr. would not be a scholar, attached those paternal hopes to this tiny new boy. The thought of a daughter becoming a scholar or theologian did not occur to him. He sent his daughters to dame schools, but secondary or tertiary education was not offered to girls.