Salem Witch Judge (23 page)

Authors: Eve LaPlante

In June of 1692 Samuel was no longer young, but he was not yet old enough to stand apart from his society. He did not think of leaving the court. He would get along, serve his country, and advance himself. A few months hence, when Governor Phips created the new Superior Court of Judicature, it would be Samuel Sewall, not Nathaniel Saltonstall, who received an invitation to join the first independent judiciary in the Western Hemisphere. In this world, at least, prudence was rewarded.

Samuel returned to Salem almost three weeks later, on July 19, for the execution of Sarah Good and the four women whom he had condemned in late June. Most of the judges were present, along with several ministers, including Noyes, and numerous townspeople. Samuel stood by as Sarah Good, whose recent pregnancy had ended with a stillbirth in jail, climbed the ladder to the gallows. He saw the hangman place the rope around her neck. He heard Sarah Good’s last words.

“Liar!” she shouted at Noyes, who stood in prayer on the earth below the gallows. “I am no more a witch than you are a wizard,” she cried. “If you take my life away, God will give you blood to drink.” Years later, when Noyes suffered an internal hemorrhage and died choking on his own blood in 1717, people in Salem would remember these words and call them prophetic.

Later, after the crowd dispersed, the bodies of Sarah Good, Rebecca Nurse, Sarah Wildes, Susanna Martin, and Elizabeth Howe were buried in shallow, unmarked graves on the hill. A witch could not be laid in hallowed ground.

Back in Boston the next day, in a strange twist, Samuel visited the house of a suspected witch. Within hours of returning from the hangings he attended a fast for his old friend Captain John Alden Jr., who was in the Boston jail.

Alden was an unlikely witch. This son of Pilgrims—Puritan settlers of Plymouth Plantation who arrived in Massachusetts nine years before John Winthrop—was a well-to-do, seventy-year-old Bostonian more established even than Samuel. Alden’s father, the “ancient of Plymouth,” came to America on the Mayflower and prior to his death in 1687 was the last surviving signer of the Mayflower Compact. Many merchants, including John Hull and Samuel Sewall, had trusted John Alden Jr. to sail their ships across the ocean. He had “nobly” commanded armed vessels for Massachusetts during King William’s War. With John Hull he had been a founding member of the Third Church in 1679. Alden and his wife, Elizabeth, who was now fifty-two, had several children and were longtime members of the neighborhood prayer group. Back in 1677 after a March prayer meeting, then twenty-five-year-old Samuel had noted, “Mr. Alden spake to 1 Samuel 15:22” on how “to obey” is “better than sacrifice.” Now it was Alden who desperately needed Samuel’s prayers.

The Court of Oyer and Terminer had sent for Captain Alden on May 28 after several Salem Village girls named him. They had heard rumors that he had traded with the French and Indians before the attack on York. He had appeared in Salem on May 31 before Hathorne, Corwin, and Bartholomew Gedney. Just two years before, Alden and Gedney had been allies jointly leading the effort to finance the expedition against the French in Quebec.

During his hearing someone told the afflicted girls, who had never before seen John Alden, that the tall man in the courtroom was John Alden of Plymouth fame. One girl cried, “There stands Alden, a bold fellow, with his hat on before the judges. He sells powder and shot to the Indians and French and lies with the Indian squaws, and has Indian papooses.” Alden had in fact made many trips to and from Maine and Acadia in the previous four years as an agent of the province and as a private trader. There were rumors that he supplied goods to the French and Indians although evidence of actual collaboration with enemy forces was scanty. His recent effort to retrieve prisoners of war in the north had met with only partial success—he freed some captives, but others were already dead and his son was out of reach, in prison in Quebec—leading some in Massachusetts to criticize Alden for bungling the mission.

Alden’s relatives, who included Quakers and other supporters of religious freedom, may have aroused suspicion, the historian Louise Breen conjectured. His wife, Elizabeth Phillips Alden, was the stepdaughter of Anne Hutchinson’s daughter Bridget, who went into exile with her banished mother in 1638. Bridget’s first husband, John Sanford, backed Anne Hutchinson and signed the Portsmouth Compact that guaranteed freedom of religion in Rhode Island: “No person within the said colony, at any time hereafter, shall be in any wise [ways] molested, punished, disquieted or called into question on matter of religion—so long as he keeps the peace.” After Sanford’s death in 1653, Bridget married the widowed Major William Phillips, a Boston wine merchant of a Quaker family. Bridget and William Phillips moved to Maine, where he amassed a fortune in land. His daughter, Elizabeth, married Captain John Alden Jr. in 1660. “One function of witchcraft accusations was to punish those individuals who had close dealing with Quakers, Indians, or Anglicans at a time when altered imperial circumstances made it increasingly awkward to act against any one of these groups,” Breen noted. “If Quakers, like Indians, stalked the perimeters of [the] settlement, seeking to pollute the true ordinances of God…, then the Phillips family, to which Alden belonged, was a catalyst of New England’s defilement and ruin.”

In Salem, at John Alden’s witchcraft hearing, the justices of the peace tested the power of his sorcery by asking him to “look upon the accusers.” The old sea captain turned toward the girls, who promptly collapsed on the floor. Aghast that the hysterical “wenches” could move the court, Alden stared at Judge Gedney. “Why did my glance not strike you down?” he demanded of his old ally, who made no reply. A little later Gedney said to Alden, “I have known you many years, and been at sea with you, and always looked upon you to be an honest man. But now I do see cause to alter my judgment.” He encouraged Alden to “confess and give glory to God.” Alden replied, “I hope I should give glory to God, and never gratify the Devil, and that God will clear up my innocency.” Gedney, Hathorne, and Corwin sent Alden to jail as a witch.

At the gathering at the Alden house on the afternoon of July 20, the Reverend Willard prayed for Alden. Samuel Sewall, who did not mention feeling any discomfort, read aloud from a treatise by the

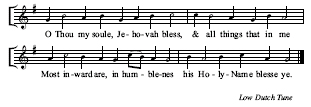

late English divine John Preston on the “first and second uses of God’s all-sufficiency,” which he earnestly hoped would help his friend in jail. Another merchant, Captain Joshua Scottow, prayed until a “brave shower of rain” interrupted him, pleasing all, as New England was suffering through a drought. Two other ministers, James Allen and Cotton Mather, dropped in to pray for Alden, followed by Captain James Hill, a deacon of the Third Church. The meeting ended before five o’clock with the men singing the first part of Psalm 103.

O Thou my soule, Jehovah bless,

& all things that in me

Most inward are, in humblenes

his Holy-Name blesse ye.

2 The Lord blesse in humility,

o thou my soule: also

put not out of thy memory

all’s bounties, thee unto.

3 For hee it is who pardoneth

all thine iniquityes:

he it is also who healeth

all thine infirmityes.

4 Who thy life from destructi-on

redeems: who crowneth thee

with his tender compassi-on

& kinde benignitee.

5 Who with good things abundantlee

doth satisfie thy mouth:

so that like as the Eagles bee

renew-ed is thy youth.

6 The Lord doth judgement & justice

for all oppress-ed ones.

7 To Moses shew’d those wayes of his:

his acts to Isr’ells sonnes.

Several Boston ministers continued to believe that the new court was not equipped to handle witchcraft allegations. More than a hundred people were now in prison. They included several men and women of evident piety and good estate. The Reverend James Allen, who knew the family of Francis and Rebecca Nurse, believed spectral evidence was wrong. He and other clergymen representing Boston’s three churches wrote to the Court of Oyer and Terminer to protest the imprisonment of Captain Alden. Their letter was penned by Samuel Willard, who had faced a case of witchcraft two decades before, in Groton. In 1672 Willard’s sixteen-year-old servant had suffered strange fits, spoken in Satan’s voice, and said a neighbor bewitched her. Willard had advised his servant to pray with the suspect neighbor, which she did, and her fits soon stopped. In the 1692 group letter Willard argued that a person whose shape the Devil assumes may be innocent. The court ignored the ministers’ pleas.

“All summer,” the historian Marilynne Roach wrote, Samuel Willard’s sermons “urged compassion for the accused, because the Devil delighted in lies.” According to Benjamin Wisner, a historian of the Third Church, “Though three of the judges who condemned the persons executed for witchcraft”—Sergeant, Winthrop, and Sewall—“were members of his church, and to express doubts of the guilt of the accused was to expose one’s self to accusation and condemnation, [Willard] had the courage to express his decided disapprobation of the measures pursued, to use his influence to arrest them, and to aid some who were imprisoned awaiting their trial, to escape from the colony.”

In a pamphlet titled Some Miscellany Observations on our present Debates respecting Witchcraft, printed secretly and anonymously in autumn 1692, the Reverend Willard criticized the legality of the court’s procedures. During several sermons that summer he preached on a relevant Scripture passage, 1 Peter 5:8, “The devil walketh up and down seeking whom he may devour.” According to sermon notes taken by the Boston merchant Edward Bromfield, one of Sewall’s close friends, on Sunday, June 19, the Reverend Willard warned against the “raising of scandalous reports” because “those that carry up and down such reports are the Devil’s brokers.” Openly assailing the value of spectral evidence, Willard told his congregation, “The Devil may represent an innocent, nay a godly person, doing a bad act” and magically assume “the image of any man in the world.”

By July the witchcraft crisis had spread to Andover, an inland town northwest of Salem, and east to Gloucester. Across the North Shore people were afraid and distracted. Farmers neglected their cattle and fields. Families began moving away.

In the Salem jail one accused witch made a valiant effort to solve the problem. John Proctor, who was chained to the dungeon floor, penned a letter to five prominent ministers of Boston’s three churches: Increase Mather, James Allen, John Bailey, Joshua Moody, and Samuel Willard. “Reverend Gentlemen,” the sixty-year-old farmer began, on behalf of himself and other condemned prisoners, we “implore your favorable assistance of this our humble petition to his Excellency,” Governor Phips, “that if it be possible our innocent blood may be spared, which undoubtedly otherwise will be shed, if the Lord doth not mercifully step in; the magistrates, ministers, juries, and all the people in general, being so much enraged and incensed against us by the delusion of the Devil…. We are all innocent persons.”

Aware that the court and community were deluded, Proctor implored the ministers to attend the trials. He requested that the trials be moved to Boston, the center of population. He informed the ministers that many suspects were tortured and coerced into confessing, in violation of English common law. Proctor cited as examples the sons of his neighbor Martha Carrier, another accused witch, and his own child.

“My son, William Proctor, when he was examined, because he would not confess that he was guilty, when he was innocent, they tied him neck and heels till the blood gushed out at his nose…. These actions are very like the Popish cruelties.” He requested that accusers be questioned separately, rather than as a group, to maintain credibility. “If it cannot be granted that we can have our trials at Boston, we humbly beg that you would endeavor to have these magistrates changed, and…that you would be here…at our trials, hoping thereby you may be the means of saving the shedding of our innocent blood.”

Proctor received no response. In early August he and his wife, who was eight months pregnant, and four other suspects were brought to trial in Salem. Based largely on the spectral testimony of the Proctors’ resentful servant, Mary Warren, Samuel Sewall and his colleagues convicted both Proctors and sentenced them to hang. In a moment of mercy the judges commuted Elizabeth Proctor’s sentence until after she gave birth.

The churches of Boston called for a public fast day on August 4 to beg God for help in fighting witchcraft. In his fast-day sermon the Reverend Cotton Mather chose as his text Revelation 12:12: “Woe to the inhabitants of the earth, and of the sea; for the Devil is come down unto you, having great wrath; because he knoweth that he hath but a short time.” The Last Judgment was near at hand, the minister prophesied. He expected it in 1697. In the meantime, he warned, Satan plotted to overthrow the world.

Satan cannot accomplish this work alone, Cotton Mather told his congregation. He needs “an army of devils.” His cadres of witches need an earthly leader, “the head actor at…their hellish rendezvouz,” someone who “has the promise of being a king in Satan’s kingdom.” By now, with the testimony of several witnesses, Mather could identify the witches’ leader. It was, appropriately, a man who appeared to be dedicated to God.