Salem Witch Judge (21 page)

Authors: Eve LaPlante

On the North Shore the number of witch suspects mounted quickly. Hathorne and Corwin now scheduled hearings in the Salem Village meetinghouse to accommodate the growing crowd of afflicted people and spectators. On March 21 the judges questioned Martha Corey, a

“saintly” woman who was openly skeptical about the witch hunt. Each time Corey answered a question from the court, the assembled girls shrieked. The girls claimed to see satanic creatures hovering around her, a yellow bird and a man who whispered in her ear. The judges asked the girls to describe these visions more clearly.

Abigail Williams, the minister’s eleven-year-old niece, called out, “Look where Goody Corey sits…suckling her yellow bird between her fingers.”

“I am a gospel woman,” Martha Corey stated.

“You are a gospel witch,” shouted the impertinent Mercy Lewis, a teenage servant of the Putnam family.

Hathorne asked Corey, “How does the Devil come in your shape and hurt the children?”

Unfortunately, Martha Corey laughed. The historian Charles Upham noted that she “repudiated the doctrines of witchcraft, and expressed herself freely and fearlessly against them” at the price of her life.

The Reverend Noyes, who had great faith in his ability to see into others’ souls, remarked, “It is apparent she practiseth witchcraft in the congregation.”

There is no record of any seventeenth-century New Englander doubting Satan’s desire to control the world and destroy God’s people. Satan was as real to them as the dirt beneath their feet. Yet he had magical powers. He could slip through a pinhole, turn into an earthly creature, and possess a person’s mind. Many pious Christians felt the Devil tempt them. The Puritan notion of visible saints—that people could recognize in themselves, and possibly in others, election by God—seemed to imply that people could recognize Satan’s allies too. This aspect of Puritan theology fueled witch hunts on both sides of the Atlantic. England’s worst witch hunt had occurred during its civil war, when Puritans ruled. In Essex, England, in 1645 a man named Matthew Hopkins accused three hundred people of witchcraft and executed about a third of them. In Essex, England, as in Essex County, Massachusetts, the trials and hangings quickly evolved into “the unraveling of the witchfinders’ deeds and lives,” the historian Malcolm Gaskill wrote. In his view, witch hunts require governmental chaos and social upheaval.

By the end of March 1692, when Samuel celebrated his fortieth birthday, scores of suspected witches crowded the jails of Salem and other towns, including Boston. The number of witches grew so fast that more judges were needed to conduct hearings. To address the problem, the Governor’s Council—Samuel was finally willing to call the General Court by this name in deference to the new governor, Phips—decided to convene in Salem on April 11. By mutual consent, Deputy Governor Thomas Danforth and four assistants—James Russell, Isaac Addington, Samuel Appleton, and Samuel Sewall—traveled to Salem for this meeting.

At this point in his life, forty-year-old Samuel had much to be grateful for: five living children, a loving wife, a rich spiritual life, a comfortable estate, and a powerful role in the government of a country he loved. Prudence had served him well.

Yet he wrote nothing in his diary during the two weeks prior to this visit to Salem, omitting even his customary mention of his birthday. He was tongue-tied, too uncomfortable with current events to set down a thought. Even after he began to comment on the witch hunt he was tight-lipped. In a typical six-month period his diary writing takes up more than fifteen published pages. During the dramatic six-month period of the witch hunt, from April 1 to October 1, 1692, he filled only six pages—less than half his usual output. Clearly, he did not know what to say.

Well before dawn on Monday, April 11, 1692, Samuel and his horse ferried across the mouth of the Charles River. They headed along the bank of the Mystic River toward Salem, a route his horse knew by heart. Samuel wore leather boots, cotton drawers, a linen shirt, warm breeches held up with a sash, a heavy waistcoat, a cravat or neck cloth, and a dark felt skullcap. Having entered middle age, he had a soft belly and long brown curls touched with gray.

Traveling to the North Shore usually filled Samuel with hope. This time, though, his heart was heavy. The Devil was assailing the region he called home. As a judge of the court, he was required to take seriously any charge of witchcraft. Colonial laws against witchcraft arose from a 1604 English civil statute, enacted by Parliament with King James I’s support, that defined witchcraft as a felony punishable by

hanging. Over the past half century New England courts had tried about a hundred people for witchcraft. Four women—Achsah Young in Connecticut and Margaret Jones, Anne Hibbens, and the Irish washerwoman Mary Glover in Massachusetts—had been convicted and hanged. Looking to the Bible for guidance, Samuel found a strong message in the book of Exodus: “One must not suffer a witch to live.”

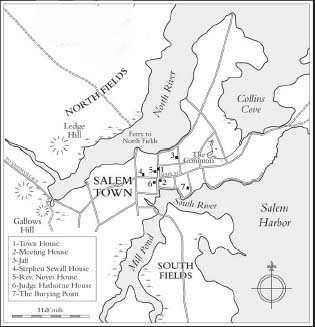

Samuel reached Salem town by ten o’clock that April morning. The court was to convene at eleven in the meetinghouse, which was larger than the Salem courthouse, to accommodate the crowd. Samuel turned his horse over to a manservant and spoke briefly with his brother

Stephen, who was present as a scribe and as the clerk of court. The bulk of the records of the witchcraft court would later be destroyed by persons unknown. Of those records that survive, most are believed to have been penned by Major Stephen Sewall.

Leaving his brother, Samuel joined his colleagues from the Governor’s Council, who would be asked to judge the validity of the complaints against the suspects. Marilynne Roach, a historian of Salem, wrote that the deputy governor and “out-of-town assistants”—Sewall, Russell, Addington, and Appleton—“presumably observed” the proceedings “while John Hathorne and Jonathan Corwin presided as local magistrates.” Men, women, and children flowed into the meetinghouse. Watching the “very great” crowd gather, Samuel had a sense of foreboding. He had never before seen such excitement over a preliminary hearing of suspects.

His friend Nicholas Noyes quieted the crowd and began the meeting with a prayer for colony’s health in the face of “devilish powers.” Samuel prayed in earnest that the Devil would be destroyed. The Reverend Samuel Parris moved to the front of the room. He produced three new suspects for questioning. Unlike the earlier suspects, these people were widely respected and comfortable financially, and one of them was male.

One of the three, fifty-four-year-old Sarah Cloyse, the wife of a Topsfield farmer, Peter Cloyse, was the youngest and feistiest of three aging sisters who would go to jail that summer. Her oldest sister, Rebecca Nurse, a Salem Village grandmother, was already in jail. Cloyse would be the only sister to escape death on the gallows. During the previous winter she had offended Parris by leaving his meetinghouse while he preached, slamming the door. During this hearing John Indian stated that Cloyse “choked me and brought me the Devil’s book to sign.” Questioned by Hathorne and Corwin, Cloyse said she had done no such thing. Parris’s eleven-year-old niece described an elaborate vision of forty witches, including “Goody Cloyse,” gathering to “take communion.” At this, Sarah Closye fainted. The judges ordered her to jail to await trial.

John Proctor, a respected sixty-year-old farmer, had a considerable estate in Salem Farms (now Peabody, Massachusetts), a wife, Elizabeth,

who was also present for questioning, and several children. His nineteen-year-old servant, Mary Warren, had implicated both Proctors after John chastised her for saying that a neighbor was a witch.

Proctor’s testimony had a profound effect on Samuel. As the farmer spoke, several girls in the meetinghouse screamed and gasped. Some girls fell on the floor of the meetinghouse and seemed to suffer convulsions. While Samuel had been told of these outbursts, he had not understood how frightening they could be.

Until now, Samuel’s experience of witchcraft was secondhand, through reading or gossip. Six years earlier a relative had mentioned “a maid at Woburn who ’tis feared is possessed by an evil spirit.” Actually seeing the phenomenon was more troubling than he had imagined. That afternoon, as soon as the Reverend John Higginson completed his closing prayer, Samuel rode straight home to Boston. Meanwhile, the Proctors and Sarah Cloyse were put in chains in the Salem jail.

Later, in the margin of his diary entry for April 11, 1692, Samuel added the words, “Vae”—“woe to”—“Vae, Vae, Witchcraft,” as if the sins of that day could be commanded away.

To an educated seventeenth-century Englishman, questioning the existence of witches and spirits was akin to questioning the existence of God. The invisible world of witches and spirits was considered evidence of another invisible world, that of God. Defending the mystery of both worlds, Increase Mather wrote in his Essay on Illustrious Providence, “There are wonders in the works of creation as well as providence, the reason whereof the most knowing amongst mortals, are not able to comprehend.” Joseph Glanvill, a seventeenth-century English minister who compiled witch stories, observed that to deny witchcraft “is equivalent to saying, ‘There is no God.’…” Roger Hutchinson, a sixteenth-century Puritan theologian, wrote, “If there be a God, as we most steadfastly must believe, verily there is a Devil also; and if there be a Devil, there is no surer argument, no stronger proof, no plainer evidence, that there is a God.” The Puritan divine John Weemes added that if people will “grant that there are devils, they must grant also that there is a God.”

Decades after 1692, the great eighteenth-century English legal theorist Sir William Blackstone would state, “To deny the possibility,

nay, the actual existence, of witchcraft and sorcery is at once flatly to contradict the revealed Word of God, in various passages both of the Old and New Testament; and the thing itself is a truth to which every nation in the world hath in its turn borne testimony, either by examples seemingly well attested, or by prohibitory laws, which at least suppose the possibility of commerce with evil spirits.” As late as the early nineteenth century the English physician and philosopher Samuel Hibbert wrote that “giving up of witchcraft is, in effect, giving up the Bible.”

That was something that Samuel Sewall and many others were not willing to do.

SPEEDY AND VIGOROUS PROSECUTIONS

On the evening of Saturday, May 14, 1692, the frigate Nonsuch sailed into Boston harbor, bringing Increase Mather and the province’s new governor, Sir William Phips, home from England. Sailors rowed Mather and Phips ashore. Eight companies of soldiers escorted the two men to the Town House, where candles burned in every window. As the twenty-four-hour Sabbath had already begun, Samuel and others ensured that there were no volleys of guns.

On Sunday morning troops escorted Phips from his North End mansion back to the Town House, where “commissions were read and oaths taken,” Samuel noted. Eighty-seven-year-old Simon Bradstreet stepped aside as governor, and Sir William was sworn in. Phips, despite his failure at Quebec, remained popular: at Boston’s recent annual election of town meeting members and court deputies on May 4, for which he was not present, he received the most votes, 969. He delivered to the province its new charter, issued by King William and Queen Mary the previous December. This Second Charter—second to Winthrop’s—was not what the men of Boston wanted but it was what they had.

The new charter dramatically reduced their right to self-government. Under the old charter local freemen chose the governor and other

members of the General Court, which in the 1640s split into two houses, the lower consisting of deputies and the upper consisting of assistants, or councillors. The new charter called for England to appoint the governor—with some prompting, as in this case, from provincial emissaries. If conflicts arose in Massachusetts, its citizens could now appeal to the Privy Council in England, which now superseded the General Court as the highest administrative, legislative, and judicial power in New England.

The new charter also changed the structure of the provincial government, splitting and dividing many powers previously held by the Great and General Court. It called for an independent judiciary—that is, judiciary bodies separate from and independent of the administrative and legislative functions of government. This change would have a profound effect on the evolution of American government, which enshrines the notion of the separation of these powers. Prior to May 1692 New England had “no court system in the modern sense,” according to Elizabeth Bouvier, the early-twenty-first-century archivist of the Massachusetts court. Prior to the new charter the colony’s “judicial, administrative, legislative, and executive functions—as well as the religious authority—were all intertwined in the General Court.” After 1692 the royal governor was empowered to create new independent courts as he saw fit. The new charter also called for grand juries to be elected locally each year and a system of county courts to meet every month or two to handle conflicts within regions.