Scribbling the Cat: Travels With an African Soldier (12 page)

Read Scribbling the Cat: Travels With an African Soldier Online

Authors: Alexandra Fuller

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Personal Memoirs, #History, #Military, #General

“What?” I dropped my cigarette into the bottom of the boat.

“I asked Him, ‘Why do you send her to me if she is not the one?’ ”

I found the cigarette before it could roll into the greasy film of petrol, water, and oil in the back of the boat. “God, that was close,” I said.

“What?”

“We nearly blew up.” I drowned the remainder of the cigarette in a sludge of beer at the bottom of a bottle.

“Why did He send you, if you are not it?”

“But He didn’t send me,” I pointed out. “I came of my own accord. I came to see Mum and Dad.”

“Ja, but then, why did He send them?”

“You’re reading too much into this.”

K was silent for a while and then he said softly, “Ja

,

maybe. Maybe.”

The boat gurgled against a ruffle of current. A swoop of bats skated out from the trees and swerved across the top of the water following the flutter of night insects.

I said, “Don’t worry. Someone will appear.”

“Maybe. Maybe not. I guess I’m happy either way.” But he didn’t sound happy.

I lit another cigarette and kept my hand cupped around it this time.

It was the time of day that hurries too quickly past, those elusive, regrettably beautiful moments before night, which are shorter here than anywhere else I have been. The achingly tenuous evening teetered for a moment on the tip of the horizon and then was overcome by night and suddenly the business of returning back to shelter was paramount. It is the time of day the Goba call rubvunzavaeni, “when visitors ask for lodging.”

K said, “The Good Book says, ‘Thou shalt not yoke yourself to disbelievers.’ ”

“That’s me,” I said. “Disbelieving Thomas.”

K smiled. “Ja.”

“I think God also said something about not yoking yourself to married women.”

K laughed. “No,” he said. “He was right. You’re not the one.”

“Nope.”

Then we drifted in companionable silence until the evening star appeared and pointed the way home.

“Time to go back,” said K.

I took my place at the front of the boat (I was on the look-out for hippos and rocks that I now would not be able to see in any case). I said, “A priest from the Chimanimanis once told me God made Africa first, while He still had imagination and courage.”

“Ja,” K said. “Struze fact. Although how would I know? I’ve hardly seen the world. A swimming pool in Holland when we were playing underwater hockey and the arse end of a blinking sewer in Turkey about sum up my traveling experience.”

I smiled.

“And South Africa a few times. And Mozambique,” said K, lowering the propeller into the water. “I’ve traveled there a whole hobo.”

“Have you been back there since the war?”

K said, “To Beira only. I’ve never been back to Tete. That’s where the kak was during the hondo

.

Long kak in Tete.”

I paused and then said, the words tumbling from my lips before I had a chance to catch the thought that preceded them, “What if we went back? You and me.”

“What?”

“To Mozambique.”

“Why the hell would you want to go to Moz?”

“I could write about it and you could get over your spooks.”

“Write about what?”

“I don’t know. You? The war?”

“No ways, man. You want me to end up in Ingutchini?”

K started the engine and curled the boat up toward Mum and Dad’s camp, taking us back over our own wake and spinning up quickly so that my feet, dangling over the edge of the water, were lifted high above the surface and I was only occasionally sprayed with stray droplets.

Just before the boat nosed into the cutting, K suddenly shouted to me, “Okay.”

“What?” I shouted back.

“I’ll go.”

The nose of the boat caught an eddy and was spat back into the current so that I had to lean to one side to avoid getting tipped off the end of the boat.

“I’ll go to Mozzy with you.”

Oh God, Pandora, I thought. What have you done?

K cut the engine and we thumped into the damp bank. I jumped to shore with the rope and tied the boat.

“Just don’t blame me if we get scribbled.”

“What?”

“I think I used up all the luck I’m ever going to have against land mines. I’ve gone over three and I’m not dead yet. Four might be the unlucky number.”

PART TWO

Mozambique

Munashe’s blissful time with Chenai in Chimanda did not last because instead of the scars of the war littered around the area bringing him relief and some measure of reconciliation with that brutal time as he had anticipated, he felt his suspicions crawl back and he began to be afraid that something might leap out of the nearest bush and pounce on him and Chenai saw it and asked him what the problem was.

“I think I need to go further,” he replied, looking at the range of blue mountains across the border inside Mozambique.

“I don’t understand.”

“I think I was terribly mistaken,” he said as if he was talking to himself. “There is no way I can reconcile myself with the ghosts of war without beginning in Mozambique.”

➛ From

Echoing Silences

by Alexander Kanengoni

Accident Hill

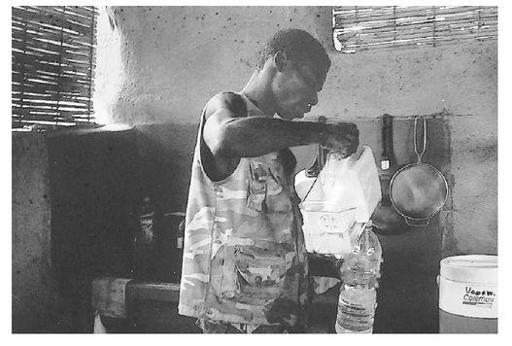

Innocent in the kitchen on K’s farm

FOUR MONTHS LATER, in early February, I flew from the States to Lusaka. K was there to meet me at the airport. As I pushed past the crush that had congregated around the customs officials, I could see him standing head and shoulders above everyone else, his breadth creating a vacuum of space around him. He looked even healthier and more powerful than I remembered, as if he had grown younger somehow since I had been here last.

“You look well,” I said.

“I’m fasting.”

“You’re not eating?”

“No, I’m eating. Just no meat, tea, coffee, soft drinks, flour, sweets.”

“Ah,” I said. It showed in his face—he radiated vigor and a kind of purity, like an athletic monk.

“Thanks for meeting me.”

“Hazeku ndaba.” K seized my bags and strode ahead of me out into the humid swell of the African air, which I swallowed in hungry, happy gulps.

“Is it good to be home?” he asked.

“Always.”

“Are you hungry?”

“Nope.”

“I saw your mum and dad last week.”

“Oh good. Are they okay?”

“Ja. Looking forward to seeing you when we get back from Moz.” K swung my bags into the back of the truck and tied them down with rope.

I climbed into the car and K handed me a carton of cigarettes. “Gwai,” he said.

“Oh man, I just quit again,” I said, lighting one. I let the smoke curl around my tongue before exhaling. “Toasted tobacco, no additives,” I said. “Yum. Tastes like childhood.” We were racing past the cattle ranches that line the road from the airport and onto the Great East Road, which headed to Malawi on the one hand and into Lusaka on the other. YOUR FAMILY NEED YOU, a sign at the intersection reminded travelers, WEAR A SEAT BELT. USE A CONDOM.

Lusaka was at its most beautiful, extravagant with the end of the rainy season. The sky stretched above the city clear and fresh. Green pushed up on every available patch of earth. Even the shanties managed to look picturesque, hiding their poverty behind stubby hedges of bougainvillea and tins containing elephant-ear plants. A large white poster flapped at the pedestrian crossing: PREVENT CHOLERA, it instructed next to cartoon pictures of a pair of disembodied hands performing various ablutions.

We cleared the overpass that avoids a tangle of railway lines and the congestion of the bus and train stations and circled past the Family Planning Building and made our way down Cairo Road, where bright gardens and fountains have replaced dust bowls at traffic circles and where coffee shops and meat-pie take-out restaurants have replaced a ghost strip of broken windows and litter-strewn gutters.

And then we were peeling out of the city, past the Second-Class District with its open-air butcheries (goat and cow carcasses, swinging from trees, seething with flies), past MundaWanga Wildlife Sanctuary (a happily restored botanical garden, which, a few years before, had been an enclosure of abused, terrified, and starving wild animals), out toward the hills that surround the town of Kafue, and into the escarpment from which we could catch glimpses of the Sole Valley.

There is a section of the Pepani Escarpment nicknamed Kapiri Ngozi meaning, in Nyanja, “accident hill.” Ngozi in Shona can also mean a “vengeful or unsatisfied ghost” and the road is correspondingly disturbed; spilled oil, torn tarmac, shredded guardrails, vandalized wrecks. Every week, at least one lorry is turned onto its back here, like a giant, marooned beetle. Fierce heat pumping up from the Sole Valley and the relentless grade of the road combine to overwhelm the brakes of the trucks that chew steadily up and down this spine of road—on their way through Zambia, into and out of Zimbabwe, the Congo, and Tanzania.

Sometimes, an accident on Kapiri Ngozi can hold up the flow of traffic on the escarpment for a week or more, and when this happens, entire, spontaneous villages erupt out of the face of the hill: green tarpaulins cast between sparse msasa trees, small cooking fires spire funnels of gray-blue smoke, and men stripped to the waist hunch in front of disabled vehicles. Prostitutes appear from Sole to administer to the stranded drivers. Women haul their baskets off the roofs of buses and set up stalls selling drinks and biscuits and roasted corn.

When we arrived at the escarpment we found a chaos of cars, vans, buses, and trucks. A lorry had lost control coming down Kapiri Ngozi, narrowly avoided tumbling over the edge into the deep valley below, and had jackknifed across the road. A curse of confusion had ensued. There were a mass of passengers and stranded travelers straggling from one vehicle to another or draped under shade on the side of the road. Fires had been kindled and the trader women were already arguing over the most favorable vending positions. A policeman was taking cover behind a plump woman trader, from where he occasionally bleated directions that went largely ignored.

K got out the cab. “Let me go and see what has happened.”

He disappeared into the milling crowd. A small boy appeared and offered to sell me a jerry can of pilfered diesel.

“No thanks.”

The boy poked his head in the window and his swiveling eyes took in the contents of the cab. “Money!” he demanded at last.

I shook my head.

“Give me!” he said.

“No.”

“Why won’t you give me? Give me!”

I closed my eyes, but the boy still breathed on me. “Hunger,” he declared at last.

“Okay.” I searched the cab and found a banana and some biscuits. “Here.”

“You shouldn’t do that,” said K, appearing at my side. “You’ll make a beggar out of him.”

“For God’s sake,” I said, looking after the boy, who had sauntered to the next vehicle with his jerry can, “he’s a child, not a Jack Russell.”

K’s shoulders sagged. “Myself, I always give to blind people. The Almighty is very specific about that. But if you try to help everyone . . . you can’t help everyone.”

A group of men who had scrambled up to the cliff above the road were now heaving boulders over the edge to create a bridge on the side of the road on which the lorry could be circumvented.

“How does it look up there?”

“Oh, we’ll be here for hours,” said K. “Half the drivers are fighting and the other half are inspired with liquid intelligence.”

“With what?”

“They’re drunk.”

“Oh”—I stared out the windscreen without surprise—“well, that doesn’t seem like such a bad idea, considering the alternative.”

K laughed at me and, as usual, I was surprised by how sudden and generous his laugh was and by how this one gesture shaved the edge off the part of this man that I found most terrifying and unattractive. “I’d get out there and do something, but I’d only end up killing someone,” K said. He sounded helplessly resigned, the way other people might say, “I’d help you do the dishes, but I always seem to break plates.”

“Better not,” I said.

“I punched a guy here last year.”

“A South African,” I said. “I heard.”

“See?” said K. “Shit. My reputation! That’s why I won’t fight anymore.” K sighed. “Wherever I go people have heard about me before I even arrive. And the thing is”—K spread out his hands—“I’ve never punched anyone who didn’t deserve it. I’ve never gone looking for a fight in my life.”

I leaned back on the front seat so that my feet could dangle out the window and catch the weak puff of warm wind that lifted off the valley floor and up the escarpment. I lit a cigarette and watched the smoke trickle off the tips of my fingers. “How many people do you reckon you’ve punched? I mean, put on the floor.”

K looked down at me for a long time, considering. “I don’t know,” he said at last. Then he asked, “Not counting the war?”

“Not counting combat,” I agreed.

“Maybe a couple of hundred.”

“Two hundred!” I said, sitting up.

“Hey, I’m not proud of it,” said K.

“And how many of those ended up in hospital?”

K shrugged. “Well, I put three in at once, does that count as three people or one?”