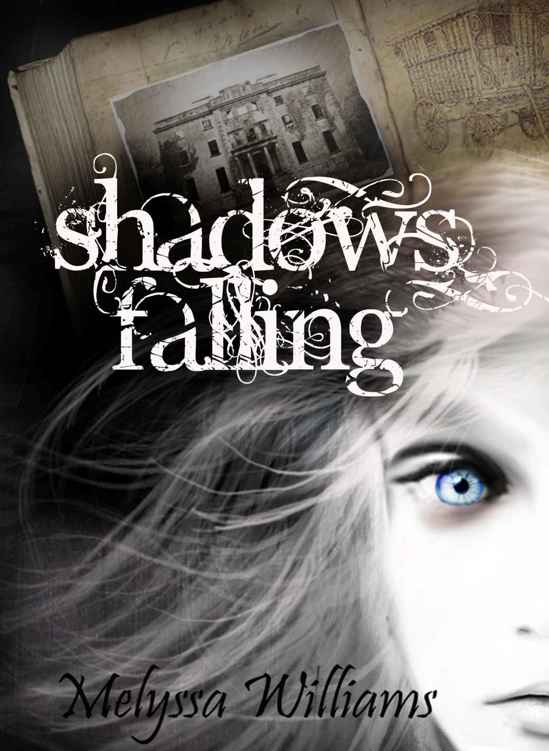

Shadows Falling: The Lost #2

Read Shadows Falling: The Lost #2 Online

Authors: Melyssa Williams

Shadows Falling

By

Melyssa Williams

This book is a work of fiction. Any references to real events, locations or people are used fictitiously. Names, places and events are the products of the author’s imagination and any resemblance to actual people, places, or events is purely coincidental.

©Copyright 2013

Melyssa Williams

Cover Design by Genesis Kohler

All rights reserved. This book and its parts may not be reproduced or copied without the author’s permission. The author may be contacted at

www.shadowsgray.com

Prologue:

From the diary of Rose Gray

Death came t

o me in a cornflower blue dress.

1

The diary came to me in 1931 after most of the patients at Bethlem Royal Hospital had been transferred. It had been tucked behind a crumbling bit of stone in one of the bedrooms, and there was nothing but the plain red ribbon bookmarker trailing out, like a saucy child’s tongue stuck in the wall, teasing me. Thumbing through rather quickly, as my supervisor, Miss Helmes, would be along shortly to berate me for dawdling, I saw entries made in pencil, scrawled in uneven, childlike handwriting. There were no dates to place the journal, though the papers inside the red binding were yellowed, perhaps with age, and I was nearly afraid to handle it, and only the name on front to say who the author might be. I had never heard of the woman, Rose Gray. My curiosity at the diary could not be denied (I have always been woefully curious), and I pocketed it in my apron.

Would that I had not.

The nurses say, and so does Luke, that it is good for my mind to journal my thoughts or write pretty pieces of poetry and nursery stories, as a good little girl ought to do. Plus, my mind seems to be going and they think this will help. They are foolish and speak of things they do not know. I hate the writing, and I have no interest in penning my memoir, yet the boredom in this place makes one do things they promised themselves not to. Take old Louis, who is belting out raunchy rhymes in a terribly bad operatic voice as he wanders the halls in his ship captain’s tri-cornered hat. I certainly think had he paused to think in his early, saner days, he would have declared that to never be.

Ah, love and hate and sleep and tedium, they make us do the strangest things. Eventually, even the strange becomes mundane in this place.

And I suppose my life has been interesting enough. More interesting than most.

Just the first few lines penned draw me in like a moth to a flame. And like a moth, I feel like I may not know what I’m getting myself into. Will I look back someday, years and years from now, and say, “Had I known then what I know now, I would have returned the diary to its place in the wall, or perhaps burned it?” Once opened, will it become a Pandora’s box to a teenage nursing student with too much time on her hands and too much inquisitiveness to spare? I am being dramatic again.

The scrawling penmanship is at odds with the sophisticated wording, and I cannot keep myself from reading further about this strange woman. Why had she been at Bethlem Royal Hospital

, more commonly known as Bedlam? I wondered. How long ago did she roam these halls? Was she among the patients transferred to the countryside during this very transition or had she been a patient here long, long ago?

My apron pocket secrets Rose and her stories for the time being as I clean and tidy and collect necessities from the asylum. There are many things to distract me as I move from room to room, and I move quickly indeed, not wanting to linger in these rooms of madness and death. Though I am extremely interested in the things of the medical world, insanity is not particularly an area in which I feel compelled to study further. Beyond, of course, the common and vulgar nosiness that we all feel in such subjects (though I hate to

admit such a curiosity), I think the mad to be quite sad and sorrowful, and I do not entertain any lofty thoughts of rescuing them from their demons. That is beyond my capabilities as someone with knowledge of herbs and tinctures and remedies and the occasional setting of a broken limb or the delivery of a babe. The brain is an area of which I have very little knowledge, and I am more engrossed in the rest of our physical parts.

No, being at Bedlam i

s a direct order from a supervisor, a low position that no one important in the medical world would stoop to, one that a mere girl my age, an orphan with an insatiable desire for education (particularly of the medicinal kind) would jump at. My supervisor is something of a legend among my peers (not that there are many peers in my field, mostly young men and old men and well, just men), and I will, I admit, do whatever he asks of me. This packing and moving is, quite frankly, last on my list. In my schoolgirl fantasies, I suppose, he would ask me to be his personal assistant or need my help in a difficult surgery, but sadly for me, all he desires is my grunt work, which any errand boy of eleven could easily do. In fact, this hospital would run more smoothly had we more errand boys, which probably explains why I am treated as such.

So I collect the instruments he needs for the relo

cation of Bedlam: the tiny, delicate things that look like something in a mother’s sewing basket (though I never had a mother, so I speak of things I do not know), the frightening, larger things that are dull and could only be compared to a saw, the notes, the medicines, the drugs. Mostly things that were left behind as they deserted this building, nothing particularly interesting in the grand scheme of things. There are still a few patients here: the particularly frail and old, a lady expecting a baby soon, a couple which is supposed to be collected by their family as their term here is coming to a close and they are deemed “cured.” I know them all by name, but I know no Rose Gray.

There is nothing overly appealing here but the diary, and it I keep. It feels heavy in my apron as I move about, the same way my red lipstick feels heavy on my lips. The lipstick was a gift from my girlfriend, Mina, and I am still getting used to the feel of it, though I reapply the thick, matte stuff every couple of hours when I know Miss Helmes isn

’t peering at me with her eagle eyes. The woman is a master spy if you ask me, and I wouldn’t be surprised to hear her start speaking with a suspicious accent and begin flying the wrong flag from her considerable bosom.

“

Put those back immediately!” Miss Helmes’ high pitched voice breaks through my thoughts like a scythe through soft wheat. Speak of the devil herself.

I sigh and plop a

stack of documents I had been idling rifling through back onto the dusty desk where I had found them.

“

They looked important, Miss,” I argue, half heartedly, though I’ve no mind to lug them back down the endless flights of stairs of Bedlam anyway. “Don’t you think the doctor might want them? For his records, I mean?”

Miss Helmes snatches them out of my hands and nearly snaps my wrist in the process. Gentleness is not this spinster

’s specialty.

“

You’re here for other reasons, Lizzie, and it’s not for smartin’ off with me and forgettin’ your place. Don’t touch anything you weren’t told to, girl. Why must I always be telling you that? Off with you now.” Miss Helmes is gone as quickly as she had appeared - the rotten apparition that she is.

Of all the hospital staff, Miss Helmes is the worst. She looks like an eagle, with an unfortunate beaked nose, and is as skinny as a rail, except for her rather well endowed bosom, which I know I mentioned before. Really, she has the figure of a Gibson Girl, but the personality of the Wicked Witch of the West, a recent book I am rather fond of. Well, not recent exactly, but finding books after war time and especially when you

’re an orphan, leaves you pathetically behind the times when it comes to modern culture. Had I chosen my birth I would have picked someplace glamorous like New York City, where my mother would wear the finest perfume and heels, and my father would work in a fabulous bank and come home each night to embrace his daughter. We’d eat steak and cake and sip cocktails like everyone in the magazines do, and when I’d find my Mr. Right, Father would shake his hand and sternly tell him to take care of the love of his life. Also, I’d have one of those fabulous bobs all the American girls are sporting, and I’d wear long strands of necklaces. Once again with the drama.

Sadly for me, I was born to parents who didn

’t love me enough to survive the war, and as a result somehow I was left here in desolate London, a place as nearly gray and dreary as Dickens painted it to be with his depressing pen. Of course, not all is bad; I do have Mina, and I do have my health.

And I do have Miss Helmes.

Lord help me.

Eventually, my hands are full, and my arms are performing an insubstantial acrobatic dance of ridiculous proportions as I wield my loot towards the stairs. A stack of precariously placed surgic

al instruments with dull edges nearly fall and with terror for my feet and toes, I yelp and stagger back, and down they go. They clatter with an ungodly crash below, and the echoes seem ludicrous in their volume. I expect Miss Helmes to come rounding the bed at any second, shouting at me to behave, to act like a lady, to do what I’m told, but all is silent, eerily so. I pick up the rascally instruments, shivering as I do so because now I’ve gone and allowed my imagination to run wild again: picturing these things being used. So dull that excessive force must have been used to slice through any type of skin and bone… I quickly blink and order my thoughts to behave.

I feel the diary in my pocket, and some premonition of tragedy causes my skin to prickle.

“Goosebumps,” said an old beggar woman to me once. “Someone’s just walked on your grave, little girl. On your grave.”

I

rub my arms briskly, reach the bottom of the stairs, and find I am not so eager to shake Miss Helmes’ presence after all. I locate her quickly (she is taken aback at my relief when I do so, and the look on her pinched face would have seemed comical at a different time, but I am too relieved to laugh), and we finish our work in our usual silence. The rest of the afternoon passes uneventfully, and when I am finally curled up in my bed in my own little flat, I am so weary and tired and hungry from my pitiful supper of toast and milk that I fall asleep, forgetting the diary entirely.

********************

The morning dawns as dark and lackluster as one could expect from an England morning in April. My inner body clock has always wakened me promptly at six a.m., and though I am tempted to pull my thin sheet over my head and deny the time, I know I cannot linger in bed like an invalid. I have never been a sickly girl, and my small body has always been as strong as a horse. When other girls got sickly at the orphanage I was usually instructed to tend them, seeing as how my constitution was so virile and so healthy. Maybe that’s where and when my interest in medicine arose in fact; in smoothing back those fevered brows and coaxing broth between parched lips. In any case, I had to choose some sort of way to support myself when I was too old to be adopted by some wealthy (and wholly imagined) patron, and the orphanage superior kicked me out on my ear at the ripe old age of sixteen. I’ve been on my own now for over a year, and though the silence bothers me sometimes, I’d say I’ve made a go of it. Oh, I’m no sophisticated city girl, but I do all right. I save my coins and get along well enough, and I have my feline companion, Hamlet, to keep me company during long nights. Well, Hamlet is more of the communal, neighborhood cat, but I am fairly certain he prefers me to anyone else. I have purchased his affection with fish and make sure to remind him where his loyalty lies frequently.

I braid my hair in two plaits that reached nearly to my waist, as is my custom. I am old enough to properly pin up my hair like a lady or get it cut and curled in a more stylish fashion, but I find I can never quite fit the part. The braids are a part

of my missing childhood I am—for some reason—loathe to leave behind. Perhaps I think the second I abandon them my last chance for a carefree childhood will be gone forever. As long as I have them I am still a little girl, at least in my head, and in my soul as well.

My nurse

’s kerchief is next, and it makes me feel a bit more grown up, though it means next to nothing really (besides a free pass for a doctor to order me around like a slave). I sigh, but walk briskly to work. I am not looking forward to another day at Bedlam. Lord, how large that building is. It will be a month of Sundays before I am done running errands in that place. I’m sure it will be nearly a hundred years before Miss Helmes is satisfied and has every last needle and file and cotton swab where she wants them, and I can finally go to my eternal reward a withered old spinster, probably still wearing braids.

I am still laughing a bit at the thought when I bump into Mina.

“You shouldn’t be wandering around scaring people,” she admonishes, her eyes big and hazel. She squeezes my hand good-naturedly. “You’ll give someone a heart attack in this melancholy place.”

Mina is beautiful and smart and pretty and very privileged. In truth, I shouldn

’t like her. She should be far above my station: snobby, petty, spoiled, and mean; but in reality, she is a bit of an angel. Her family is one of the richest in the city and though she could have everything any girl could want, she is down to earth and eager and hard working and humble. I tried to dislike her—as a penniless orphan should—but she is simply impossible to hate. She is gentle with everyone and keeps volunteering here at Bedlam, even after her wealthy father informed her she had done enough and was free to stop and move on to other charitable works. She’s found her calling, she told me, and though I can’t imagine choosing to be in such surroundings, she shows up faithfully and cheerfully at least three times a week. There’s no accounting for taste, Miss Helmes says.

“

Like who? The ghosts? I’m beginning to think everyone here is already dead, Mina. Didn’t you know?” I lower my voice and try to sound spooky.

She shudders and eyes me strangely.

“That’s a terrible thought, isn’t it?”

“

Is it? I suppose. Although it’s probably nice to be a ghost. Tiptoeing wherever you like, knocking things about, eating whatever you please without fear of gaining an ounce…” I wink, so she knows I am joking. One thing Mina is a bit short on is a sense of humor. She tries, the dear thing, but she never seems to fully appreciate a joke. Maybe it’s a side effect of the well-to-do. I have yet to meet a jolly, rich person. “Can’t you picture Mr. Limpet strolling around, disappearing through walls, shouting at you for biscuits, reappearing under the table? Boo and poof and all that nonsense?”