Sharing Our Stories of Survival: Native Women Surviving Violence (14 page)

Read Sharing Our Stories of Survival: Native Women Surviving Violence Online

Authors: Jerry Gardner

We are provided a window of opportunity to make a difference in a battered woman’s life. We must use that time to help her understand why domestic violence exists. It is important to resist looking at domestic violence as a one-time assault and examine it as a pattern of abuse. This includes making a connection between domestic violence and a society that accepts violence against women in such epidemic proportions.

Advocacy (see chapter 12) is the cornerstone of our work to end violence against Native women. Advocates include community members who step forward to help. One challenge is finding advocates who clearly understand domestic violence and its roots in an oppressive system. Often, well-meaning advocates believe that they know what is best for the victim and do not listen to the victim’s perspective. This attitude is not only disempowering to women—it can also lead to dangerous and potentially life-threatening situations. Instead, advocacy should create an environment where the realities of women’s lives are allowed to be expressed even in the midst of the violence they are experiencing. An empowerment model of advocacy allows each battered woman to make choices for herself, remembering that each woman is sacred and sovereign.

Starting a battered women’s shelter can establish more options for victims. Shelters provide a safe place for women and children to live while escaping the violence. In addition, shelters can also provide financial and legal assistance. Unfortunately, the development of battered women’s shelters across Indian Country has been slow. This is due in part to inadequate financial resources. Most tribal governments have few resources available to dedicate to the development and operation of a shelter. Other funding sources have not always targeted the needs of Native women in these communities.

15

The geographic locations of reservations, pueblos, rancherias, and villages pose another barrier, since there are often great distances between communities, with no adequate transportation. There are also a limited number of physical structures that can be easily adapted into a shelter. Confidentiality and security become an issue when first responders may be hours or days away.

Mistakes to Avoid

Over the past three decades, as our tribal societies developed responses to domestic violence, we have become increasingly reliant on the non-Native civil and criminal justice systems. Our experience tells us that we have chosen responses from within a system that historically has been less than helpful. For many years, Native women have been raped at significantly higher rates than white women. Native women understand this reality and carry the burden of historical consequences when they call the police but are not believed; when their case is dismissed before the court because the judge is a relative of the batterer; when there is not enough evidence or resources to pursue the case. A Native woman understands this reality when she knows her mother was removed from their home and placed in a boarding school—or that her children were removed from their home and placed in a boarding school—or when her children were removed from her home because she could not stop her partner’s violence against her. In addition, Native battered women understand that Native men are being incarcerated at higher rates than their white counterparts. She understands that if she calls the police, her partner may have to face federal penalties for his violence (which carry stiffer consequences than state penalties.) She also understands that if she is dealing with the law enforcement system off the reservation, her partner may find himself faced with the institutional racism inherent in mainstream communities.

Our advocacy with battered women must reflect our values. Often we find that we are adopting mainstream models that are authoritative and paternalistic. These punitive models serve to reinforce battered women as defective and fail to honor individual women for who they are.

Many domestic violence agencies and organizations view domestic violence as an individual psychological problem. This philosophy poses very serious problems and can be dangerous for Native women. Often, a battered woman is sent to a therapist or offered a support group where she can “work on her self-esteem.” At the same time, batterers are sometimes sent to “batterer’s treatment.” While some women may find therapy helpful, and some batterers might also benefit from psychological intervention, it is important to not lose sight of the actual causes of violence against Native women. The danger in taking a psychological approach comes from introducing battered women into a mental health system because of the batterer’s violence. It serves to further reinforce tactics of power and control that the batterer may already be using, such as emotional abuse, minimizing, denying, and blaming.

By defining domestic violence as a mental health issue, the system fails to recognize the larger community problem of violence against Native women. This mental health approach repositions domestic violence into an individual context of one where a batterer is not directly accountable for his choice to use violence in his relationship. Instead of a criminal act, domestic violence becomes a disease. It places responsibility on the battered woman for her victimization and further reinforces the batterer’s violence.

Working to understand that different mainstream theories of domestic violence can serve to raise our ability to effectively create social change requires us to recognize that society needs to change—and to place indigenous values at the center.

We become activists by default. Suddenly, we’re representing our tribes, the Red Race, in everything we do—whether we want to or not.

—ARIGON STARR

16

(KICKAPOO/CREEK)

Native Ways of Life

Over 560 federally recognized tribes have a commonly held traditional value of respect for women, both physical and emotional. Yet we all face the challenge of incorporating this value into our everyday lives. Our traditional lifeways worked to deter violence in our tribal communities in our past and again will serve to provide us with indigenous solutions to violence against women in our future.

If we are not actively engaged in ending violence against women, we are reinforcing the violence through

complacency.

It is important that we recognize the interconnectedness of our efforts. We have made some strides toward establishing a foundation for this work and can now see a range of responses to domestic violence across Indian Country. In addition, we are learning from each other as we develop our programs. We are also reaching out to our communities to change attitudes and beliefs that were once foreign to us but have now become common and destructive. There is still much work to be done.

Today we are being challenged to find a way to reclaim the traditional values in order to return women to their rightful status in society. We are also striving to restore balance to our communities. The very foundations of our societies depend on our success. Our work will gain strength as we incorporate a response to domestic violence that does not rely on mainstream models, but instead turns to our memories of how things worked in our tribes before colonization. We will succeed when we can design contemporary solutions with traditional values at the core.

I want to 6e remembered for emphasizing the fact that we have indigenous solutions to our problems.

—WILMA MANKILLER

17

(CHEROKEE)

Figure 3.3

. Sacred Circle Natural Worldview Wheel. Source: Courtesy of Sacred Circle, Natural Resource Center to End Violence Against Native Women.

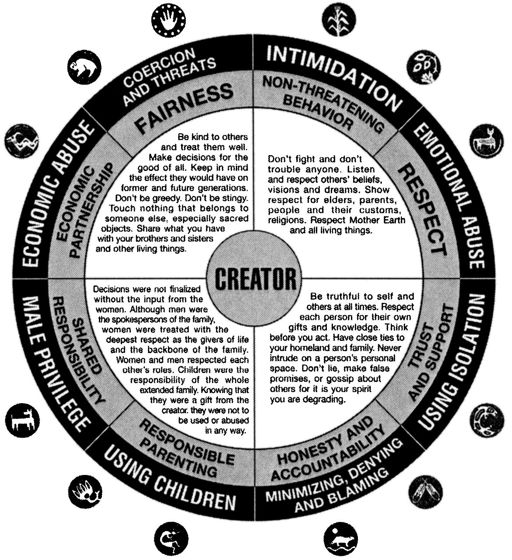

Figure 3.4. Creator Wheel. Source: Developed by Mending the Sacred Hoop.

Notes

1

www.cdc.gov/ncipc/factsheets/ipvoverview.htm

2

Patricia Tjaden and Nancy Thoennes,

Full Report of the Prevalence, Incidence, and Consequences of Violence Against Women: Findings from the National Violence Against Women

Survey (National Institute of Justice and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, NCJ 183781, November 2000), pp. 21—23. American Indian/Alaska Native women were significantly more likely than white women or African American women to report they were raped. In addition, they were also significantly more likely to report they were stalked. Data from the survey by type of victimization and race reflect the following percentages: rape—American Indian/Alaska Native 34.1; white 17.1; African American 18.1; Asian/Pacific Islander 6.8; Mixed Race 24.4; physical assault—American Indian/Alaska Native women 61.4; white 51.3; African American 52.1; Asian/Pacific Islander 49.6; Mixed Race 57.7; stalking—American Indian/Alaska Native women 17.0; white 8.2; African American 6.5; Asian/ Pacific Islander 4.5, Mixed race 10.6.

3

According to the Bureau of Justice Statistics Special Report,

Intimate Partner Violence and Age of Victim 1993—1999

(USDOJ, 1999).

4

Serle L. Chapman,

We, the People of Earth and Elders,

vol. 2 (Missoula, MT: Mountain Press Publishing Company, 2001), p. 314.

5

Many Native organizations working to end violence against Native women centralize the belief that women are sacred in their work. Two such organizations working on a national level influencing local work across Indian Country are Sacred Circle, located in South Dakota, and Mending the Sacred Hoop in Minnesota.

6

The Domestic Abuse Intervention Project (Duluth, Minnesota) developed a Power and Control Wheel that represented tactics of power and control. Struggling with having these unnatural beliefs incorporated into a wheel and recognizing additional tactics of power and control used against Native women, Cangleska/Sacred Circle later modified the tactics and placed them in a pyramid (see

figure 3.1

).

7

Through my experiences in working to end domestic violence over the past twenty years, I have talked with many battered women in many contexts. These contexts include providing advocacy, providing direct services, conducting women’s educating groups, conducting focus groups, or organizing to create social change.

8

According to the Bureau of Justice Statistics Special Report,

Intimate Partner Violence and Age of Victim, 1993

—

1999

, intimate partner violence is primarily a crime against women. In 1999, women accounted for 85 percent of the victims of intimate partner violence (671,110 total), and men accounted for 15 percent of the victims (120,100 total).

9

Murray A. Straus and Richard J. Gelles,

Physical Violence in American Families

(New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction, 1990).

10

Paula Gunn Allen,

The Sacred Hoop: Recovering the Feminine in American Indian Traditions

(Boston: Beacon Press, 1992), p. 191. Allen continues, “The amount of violence against women, alcoholism and violence, abuse and neglect by women against children and their aged relatives have all increased. These social ills were virtually unheard of among most tribes fifty years ago.”

11

Other isms may include homophobia (the expression of hatred towards or discrimination against persons of a homosexual orientation) and ageism (the expression of hatred or discrimination against persons of an older or younger age).

12

In my experience working with battered women, the vast majority of women were low-income or working-class women. I believe that women with more resources have more options available for leaving an abusive situation.

13

Some of these examples are taken from the training program

In Our Best Interest: A Process for Personal and Social Change

(Minnesota Program Development, 1987). Other examples are drawn from my experience working as an advocate for battered women.

14

Chapman,

We, The People of the Earth,

p. 114.