Short Nights of the Shadow Catcher (27 page)

Read Short Nights of the Shadow Catcher Online

Authors: Timothy Egan

From the Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology at Harvard came a note from Professor

F. W. Putnam, rapturous in his commendation of “your great work.” He had met Curtis

some years before and was an early enthusiast. Now, after seeing some of the finished

product, he praised the scholarship. In particular, he said the anthropology and ethnology

were of the highest order, considerably advancing the work of those fields. Came another,

from

Review of Reviews:

“

The North American Indian

cannot be compared with any publishing venture in the annals of American bookmaking,

or indeed in those of any other nation.” An old Curtis mentor, C. Hart Merriam—one

of the men he’d rescued on Mount Rainier a decade earlier—wrote an unqualified endorsement:

“Every American who sees the work will be proud that so handsome a piece of book-making

has been produced in America; and every intelligent man will rejoice that ethnology

and history have been enriched by such faithful and artistic records of the aboriginal

inhabitants of our country.”

FEAST FOR BIBLIOPHILE

REMARKABLE WORK ON RED MAN OF AMERICA

That was a

Washington Post

headline of a story touting “one of the most remarkable and expensive publications

ever planned.” From Geneva came a formal letter from Dr. Herman ten Kate, a leading

European intellectual: “You are doing a magnificent thing, building not only an everlasting

monument to a vanishing race, but also to yourself. I am sure that if the Indians

could realize the value and purpose of your work, and perhaps a few of them do, they

would be grateful to you. In fact, viewed in a certain light, your work constitutes

a redemption of the many wrongs our ‘superior’ race has done to the Indian. Some passages

you wrote are masterly.”

Those “many wrongs” inflicted on small nations by the much larger one continued to

trouble Upshaw. The Crow reservation, on an ownership map, now looked like a quilt

made of several thousand square scraps. Not only was the tribe still losing people—in

a generation’s time, the population had been cut in half—but its reservation was being

carved out from under them. Much of the good land, with its pasturage for cattle and

its well-watered valleys for growing grain, had passed into white hands. In all respects,

the modern age meant only one thing—decline.

“You are decreasing at the rate of three percent a year,” Curtis lamented to Upshaw

one night as he went over census numbers. “Take this pencil and figure out your own

solution.” Upshaw didn’t have to do a calculation.

“If I live to be an old man there will be none of my people left,” he said.

“There will be a few left,” Curtis replied—but only those who can master the ways

of the dominant culture.

When Upshaw wasn’t at Curtis’s side, he was in court, or in meetings with state politicians—the

public face and mouthpiece of the Crow. He started to push back in his correspondence

with the imperious government overseer Dalby. The lord of Indian country in Montana

had mentioned that he was off to Washington, D.C., for congressional hearings. Instead

of his usual lip service about trying to “be a man,” Upshaw was direct. It was crucial

that the Indian inspector stand up “in this trying time in order to get justice.”

In the last full month of Teddy Roosevelt’s presidency, Curtis was invited to Washington

for an informal sit-down with the writer-politician who had done so much for an unknown

man from Seattle. Curtis raised an improbable idea with Upshaw: why not go with him

to the White House? There, he could argue his people’s case.

In late February of 1909, Washington society opened its doors to the Shadow Catcher

and his Indian friend. The president was the subject of much speculation over whether

he would try to return to power in four years. Not a chance—he was off to Africa,

he insisted, done with politics. The balloon figure of William Howard Taft, a walrus-mustachioed

midwesterner given to long naps and multiple-course early-bird dinners, would soon

be president. For Roosevelt, it was time to play again. He asked Curtis, who’d been

such a kinetic companion at Teddy’s Sagamore Hill home, if he wanted to come along

as photographer of his upcoming African safari. Curtis was flattered, but had no time

for a yearlong diversion.

Exhibitions at galleries, clubs and the homes of political elites filled the Curtis

calendar for the first few days in Washington. He was honored at a reception attended

by Roosevelt and Taft, by ambassadors, counts, foreign ministers and “a score of the

most prominent people in Washington’s social and scientific circles,” the

Post

reported. In its pages, Curtis was described as “perhaps the greatest living authority

on Indian lore and Indian life in general.” Despite such accolades, he had yet to

snag a subscription from the Smithsonian. While in the East, he did manage to get

Andrew Carnegie to sign on for a single set of the books, and he used the praise from

prominent figures to add an additional few to his list. The checks passed quickly

through Curtis’s account and into those of Hodge, Myers, Upshaw, the printers in Boston

and other creditors.

Curtis and the Crow native walked into the White House on the afternoon of February

25. Roosevelt was hearty in his greeting and open to hearing Upshaw’s case, at least

for a few moments. That was all well and good, he said quickly, but the Indian should

take up his grievances with the new man, Taft. They toured the White House, they shared

a meal, they talked of mountain ranges and rivers in the West and of wild creatures

on the Dakota plains. Such lovely country, all of it. And the work of Curtis—

it was bully!

Curtis thanked him again for his contribution to

The North American Indian,

and Roosevelt said it was nothing; he was humbled to be a part of something so monumental.

EXPLORER AT THE WHITE HOUSE

The

Washington

Post

had numerous errors in its story on the visit, calling the grammar school dropout

“Professor Curtis” and claiming he was an “explorer” of Indian lands, rather than

someone who took pictures and explained cultures. The article said his work would

be finished in two years. Hah! Only five of the planned twenty volumes had been published.

The paper asserted there was no truth to the rumor that Curtis would accompany Roosevelt

to Africa. As for the “copper-skinned” companion, Alexander B. Upshaw, at least his

presence was noted. The

Post

called him “a full-blooded Crow Indian,” but never gave his name. At his supreme

moment of influence, this delegate from an old nation in Montana side by side with

the president, the educated, assimilated native, was not a man with a name, just an

Indian—a full-blooded one at that.

Later that year, as Curtis made plans for fieldwork with his Indian aide in New Mexico

and the Columbia River Plateau, came shocking news from Montana.

EDUCATED CROW DIES IN JAIL

Upshaw’s body was found on the floor of an icy cell, the story in the

Billings Gazette

said, blood splattered on the bars. He died of pneumonia, the paper reported. He

had been on a drinking spree, and was arrested after someone found him in a dingy

hotel room in town. In jail he started vomiting blood until it killed him. “He is

survived by a wife, a white woman,” the paper said, “whose marriage to the young graduate

of Carlisle caused quite a sensation.” Members of the Crow Nation told a different

story to people who’d worked for Curtis in Montana: they said Upshaw had been murdered.

The details were sketchy, but this version had Upshaw in an argument with several

white men. Punches flew. Upshaw was severely beaten, then dragged off to jail to die.

Curtis was heartbroken. His close friend, his best interpreter—

perfectly educated and absolutely uncivilized

—was gone, left in a frigid jail cell to gag on his own blood. They finished each

other’s sentences, these two, and in the writing of

The North American Indian

Upshaw often did that for Curtis as well. The life had been snuffed out of Upshaw

at the age of thirty-eight. On the reservation, the death of the most remarkable man

Curtis had ever met was noted only for how unremarkable it was for an Indian to die

so young.

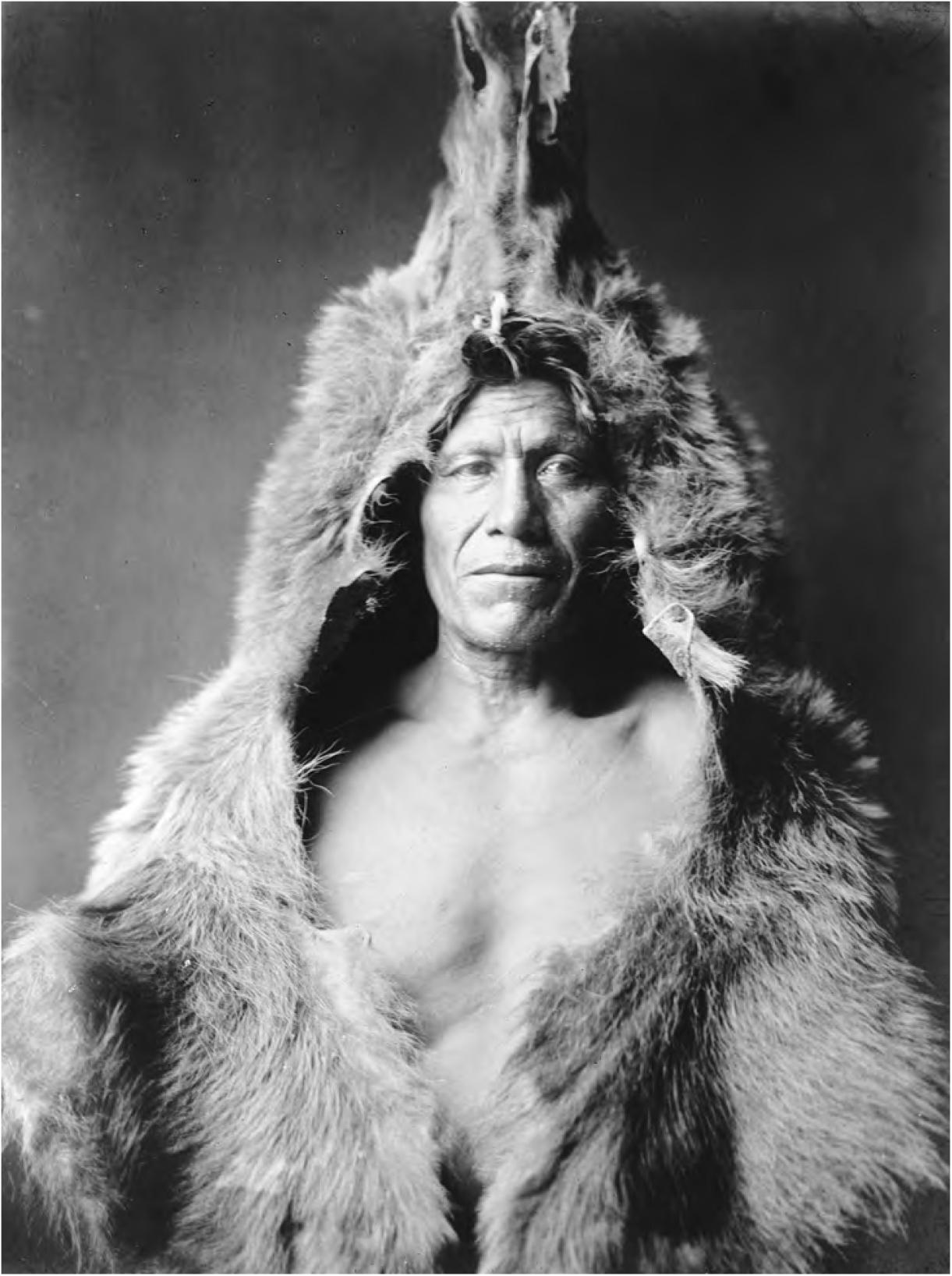

1905. Curtis’s friend and interpreter Alexander Upshaw, “perfectly educated and absolutely

uncivilized,” as Curtis said of him, had trouble shuttling between two worlds. He

chose to pose in the clothes of his ancestors.

1908. The ceremony of the bear medicine fraternity had been dormant for some time,

Curtis wrote, until it was revived for his camera.

1908. One of many remarkable scenes that might never have been recorded had Curtis

not been aided by Upshaw.

1910

I

N A YEAR, ENOUGH

water pushes through the Columbia River Gorge to bury an area the size of California

under eighteen inches of pure snowmelt. It runs 1,214 miles, this stream once full

of giddyup, from its slow-drip birth in British Columbia’s Rockies, to the steep narrowing

where it breaks the backbone of the Cascade Mountains, to a final sashay at a ten-mile-wide

mouth, emptying more river into the Pacific than any other in the Western Hemisphere.

In midspring, when snow from the high peaks of two Canadian provinces and three American

states slides downhill in a transformative rush to water, the Columbia is most engorged.

And it was at this time that Curtis, Myers, a young hired hand called Edmund Schwinke,

a reluctant old bar pilot and a Japanese cook who answered to the name of Noggie prepared

to descend the most treacherous, spray-generating stretch of what was then the largest

free-flowing river in North America.

They had built a small boat—“nondescript and flat-bottomed,” in Curtis’s shorthand—square

at the stern, bowed in front, with a small gas engine for scoot-up power in settled

water. And now they stood above Celilo Falls, where the river went into free fall,

all froth and fury. Curtis had with him the notes Lewis and Clark took when the Corps

of Discovery passed through this very place nearly a century earlier. Among all the

misspelled, bloodless observations of those nonemotive explorers, no sentences convey

more terror than their description of the canyon that lay just below the Curtis party

in 1910. They called it “an agitated gut swelling, boiling and whirling in every direction.”

Curtis was there in search of the once prosperous tribes of the Columbia. For centuries,

these natives had only to walk a few steps from their cedar-plank homes to have all

they needed to eat. At Celilo, millions of Pacific salmon made the transition from

long-haul distance swimmers to high jumpers. They had to leap up the side pools of

the falls, a fight with gravity and a down-pounding current. For American Indians,

there was no easier way to take protein. They used nets, gaff hooks, spears and baskets

to bring home the tastiest species of salmon, the oil-rich Chinook. Some years, upward

of ten million fish would pass by.