Short Nights of the Shadow Catcher (29 page)

Read Short Nights of the Shadow Catcher Online

Authors: Timothy Egan

And once Curtis had started down this narrative road, he could not stop, and did not

want to. Myers and Hodge might second-guess him, but these words would stand, because

the Nez Perce were subject to “dishonest and relentless subjection.” So, for the first

time, a gust of outrage made it into

The North American Indian.

Even after surrendering their land, after living as prisoners of war in arid country

far from the Northwest, after the tribe had been broken up along religious and treaty

factions, they faced new indignities. That, in the view Curtis now held, was the way

the United States did business with nations that were recognized as sovereign. All

of this, Curtis concluded, “is nothing more than we might have expected, for we as

a nation have rarely kept, unmodified, any compact with the Indians.” There was no

turning back; from then on,

The North American Indian

was not just a showcase of the best of the native world, but a bullhorn for a man

who had seen the worst of it.

After the near-calamitous drop down Celilo Falls, the Curtis party scooted through

several more stretches of violent white water, arriving at a place known as Bridge

of the Gods. It was no bridge but the crumbled foundations of an arch that indicated

an ancient basalt piece of the mountain had once straddled the river. It was here

that Lewis and Clark had used ropes to lower their canoes down. Myers laughed as Noggie

continued to cry.

“Take

his

picture,” said Myers, pointing to the cloudy-eyed cook. For anyone who thought the

Curtis Indian work was all glamour and exploration, the tears of Noggie would tell

another story. At Bridge of the Gods, Curtis could use the one major mechanical manipulation

of the river to date, a section of primitive but effective government locks. It was

little more than a side channel of the main river, an escalator, both ways, of water

that allowed passage. After clearing the locks, the group faced a fresh section of

swollen and enraged river. The lock keeper said he could not recall when the river

had been so high. But the old bar pilot, who had hired on with Curtis for one last

ride down the Columbia, thought otherwise—wasn’t anything he hadn’t done before. Sure,

the lock keeper said, but not in a boat as small and fragile-looking as the one owned

by

The North American Indian.

“No man alive could make it with that . . . tub,” said the lock keeper. “The currents

have changed since your day.” Curtis fired up the gas engine. He was determined to

go ahead; the tiny propeller would give them just enough oomph to get through. He

ordered everyone aboard.

“Well, Captain,” the lock keeper told the pilot, “it’s your funeral.” Curtis moved

to the bow while the pilot guided the tiller. But as they started, the sea-weathered

skipper seemed to lose his nerve.

“This ain’t navigation,” he shouted above the percussive claps of the Columbia, “this

is a boxing match . . . Ride ’em high. Don’t let a whirlpool get us.” As they plunged

through the first series of breakers, icy water crashed over them. Then, bobbing through

another round, the boat pitched headfirst, bucked up and shot sideways. The lurch

nearly threw Curtis into the river. They struggled to stay atop the crests, waves

on either side of them. They wrestled with the currents of several eddies, where the

water encircled and gripped whatever came its way, and there the engine proved a lifesaver.

In one of the whirlpools was a large tree, stripped of its branches, vertical in the

water. They had no sooner evaded that trap than a ridge of water collapsed over them.

The boat was buried, but popped up and drifted to a side where it was calmer. Soaked

and badly shaken, the men pulled their craft ashore. Noggie looked catatonic with

fear. The captain was white-faced, lips purple, body trembling. The worst was over.

But the price proved high for Curtis’s team. Both cook and river pilot said they’d

had enough. They quit and departed immediately for Portland. Now it was left to Curtis,

Myers and Schwinke. “I became both captain and cook,” wrote Curtis. That was just

as well, for Curtis had complained about the lousy food made by all of his cooks.

And that night, he showed a skill that he’d first developed as a boy braising muskrat

for his family in Wisconsin. He bought an enormous salmon from a fisherman, a spring

Chinook, filleted it and cooked it next to a fire, Indian style, on cedar sticks,

searing the outside, keeping the inside tender and moist. “It was the fattest, juiciest

salmon I’ve ever tasted,” Curtis wrote in one of his culinary digressions. “We ate

until there was nothing left but the bones.”

Afterward, the picture-taking and story-gathering took on a mournful tone. Where the

Corps of Discovery had written of long-settled communities, Curtis struggled to meet

a soul. The native people were spent by time and disease. At the site of a formerly

large village “we found only two descendants.” In other places, the tribes were gone

completely, their only trace a bit of rock art scraped onto basalt columns. Just the

“old friends” of Curtis, the Wishham, still had a somewhat active village, on the

north shore of the river, down from the falls. In talking to Wishham elders, Curtis

heard stories of creation, and of how a good spirit had vanquished an evildoer who

tied people to a log at the Columbia’s mouth and left them to die. The river’s bounty,

he was told, was a result of a god who had opened a pen where all the salmon had been

kept and let them run free forever. He also heard stories of death and decay, the

later myths conforming to the loss of the societies.

Both women and men were tattooed. They used canoes in the way inland tribes used horses.

They were sexually open, had large, permanent villages and held slaves. The collapse

arrived slowly at first and then all at once. The first wave hit after initial white

contact, when the diseases for which the Indians had no immunity—cholera, measles,

smallpox—killed indiscriminately. Alcohol was next, overwhelming people during the

late nineteenth century. This pattern was familiar in its mortal precision, and no

part of it surprised Curtis. What stood out in this case was the river. Indians would

cross the Columbia in their dugouts to trade salmon and furs for whiskey. They returned

drunk, and “whole families were thus wiped out in a moment,” Curtis wrote.

The problems for the natives now came from trying to find their way in the twentieth

century with greatly diminished numbers. The national census of 1910 had begun, and

if counters found anything like what Curtis had seen up close over the last decade—with

the Crow, the Sioux and the Indians of the Columbia River—the tribes were even more

endangered than he believed. That year, in doing advance work, Myers had found only

two surviving members of another tribe, whose name was associated with a famous Pacific

Coast oyster, the Willapa. As a conservative guess, Curtis estimated that 95 percent

of the original population along the lower river was gone. With the exception of the

Wishham, “the Chinook tribes on the river . . . were practically extinct.”

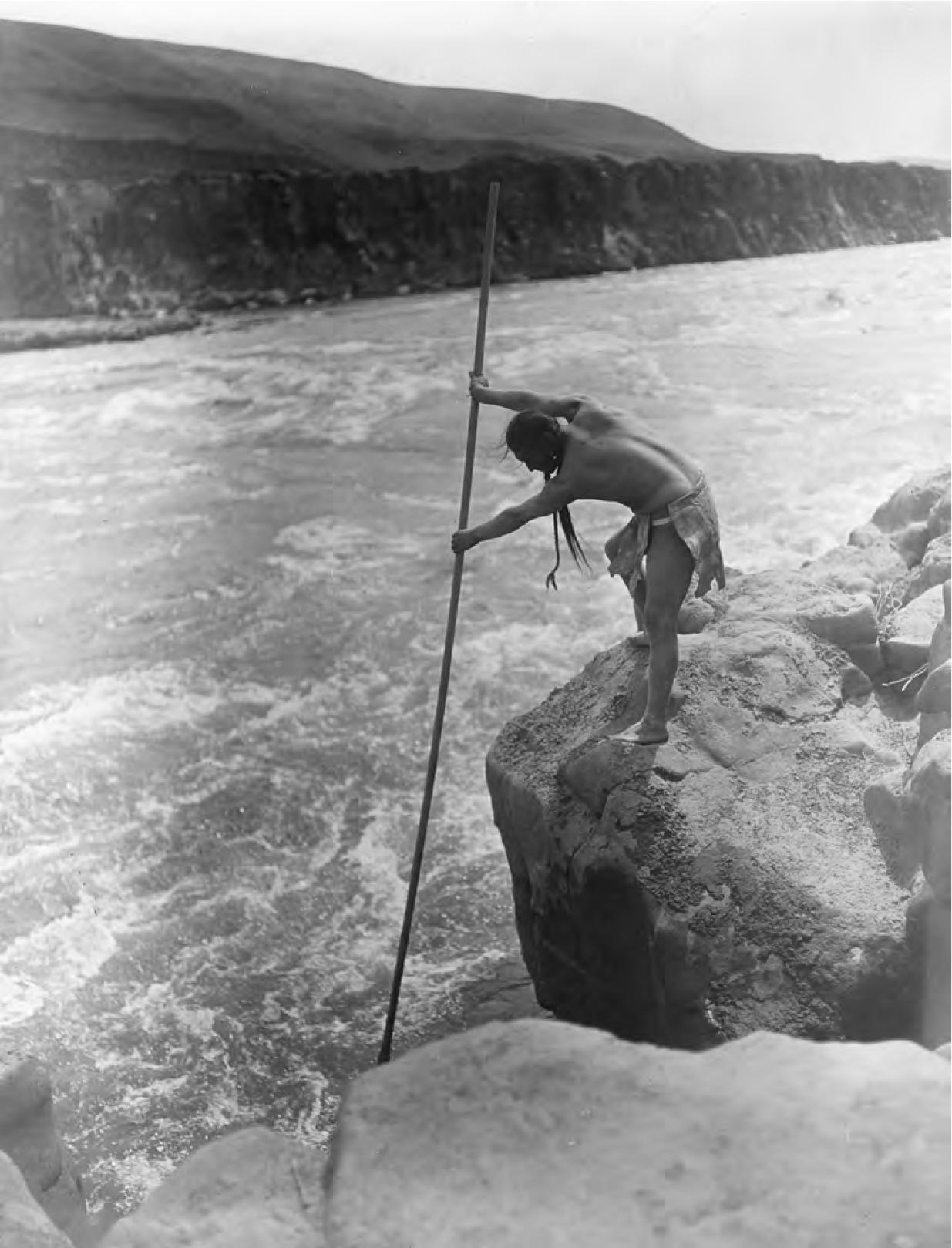

For all their troubles, Curtis presented the Wishham in their best light, from a beautiful

woman pounding salmon to a sinewy man netting fish. He shot pictures of petroglyphs,

fishing platforms and heroic people in the face of a river’s power—in line with his

original desire to have “nature tell the story.” Some years in the future, these images

would be hanging in a gallery, a museum, a home, a tribal headquarters or on the wall

of a prestigious private club, and people would see what life had been like before

all the river was flaccid, clipped by more than a dozen big dams, a “slackwater empire,”

as the writer Blaine Harden later called it.

To the ocean, the Curtis party of three pushed on, the rapids behind them, the Columbia

bar, that collision of high surf and emptying water, ahead of them. The river was

so wide it looked like a slow-moving lake, littered with the flotsam of forests. The

most productive American fishing fleet was in full frenzy along the shore, with the

canneries at Astoria packing salmon to feed the world. Curtis knew he should not risk

passage over the bar at river’s end. The biggest danger on the Columbia was known

as the Graveyard of the Pacific, where more boats had been lost than any other place

on the West Coast. In the best of times—calm, windless—it was a tussle between tidal

might and river current. Even long-experienced bar pilots guiding sea-tested vessels

found the crossing a white-knuckle drama. Sailors would tie themselves to their ship

masts to keep from being tossed overboard. Just upriver from this battleground, Curtis

anchored his tiny craft and went ashore. He picked oysters at low tide, a kind known

for its sweet, somewhat briny taste. He started a beach fire of driftwood, and stoked

it until there was a bed of hot coals. Then, with the tide rising, he unleashed his

boat and let it go—into the arms of the River of the West, away to violent swells

of the bar, “our worthy but nondescript craft adrift that it might float out to meet

the ocean breakers and be battered to fragments.” At sunset, Curtis cooked the oysters;

just a few moments on the coals and the hard shells popped open with a hiss. The men

sat on the sand at land’s end and ate their fill, Curtis, Myers, and Schwinke, all

that was left of the field team, slurping bivalves in the fading light of early summer,

wondering if the continent itself had run out of Indians.

1910. Curtis took a wild ride down the undammed Columbia River in 1910. To his dismay,

the once thriving tribes that had lived for millennia off the river’s salmon had dwindled

to a handful of natives.

1910–1913

B

ACKSTAGE AT CARNEGIE HALL

, Curtis waited for the lights to dim and the orchestra to finish tuning up. When

the hum of chatter died down, he peeked out at a house packed with pink-jowled swells

in stiff-collared tuxedos and women with jewels glittering atop perfumed décolletage.

The New York social set had paid top dollar to listen to the Shadow Catcher talk about

savages.

And more than talk: he was presenting “The Story of a Vanishing Race,” a picture

opera. But tonight’s offering was not purely opera. Nor was it all static picture

show. This touring spectacle was a uniquely Curtis hybrid. The visuals were slides

from the photographer’s work over a fifteen-year span. He had painstakingly hand-colored

the slides, so that rock walls at sunset in Canyon de Chelly had an apricot glow,

and the faces shot at the magic hour in New Mexico gave off a rugged blush. Montana’s

altocumulus-clouded ceiling could never be the true robin’s-egg blue, but it was close.

Using a stereopticon projector, or magic lantern as it was called, Curtis could dissolve

two colored-tinted pictures, creating narrative motion. He supplemented the stills

with film, some of it sandpaper-grainy and herky-jerky, but still—action! And all

of these images buttressed a story, narrated by Curtis himself, about an epic tragedy:

the slow fade of a people who had lived fascinating lives long before the grandparents

of those in Carnegie box seats sailed from Old Europe to seize their homeland. What

made the entire experience memorable was the music, from an orchestra playing a score

conducted by the renowned Henry F. Gilbert and inspired by the recordings of Indian

songs and chants that Curtis had brought home on his wax cylinders. Gilbert had been

among the first popular composers to use black gospel music and ragtime. He now took

on the challenge of translating Indian music through conventional instruments. The

whole of it was a visual-aural feast of the aboriginal, as the critics called it,

created by a most American artist at the height of his fame.

Curtis was pleased to see that “The Story of a Vanishing Race” was a sellout, especially

in Manhattan. There was no more prestigious interior space in the land than Carnegie’s

Main Hall, two blocks from Central Park, a venue then twenty years old and home to

the New York Philharmonic. But when he looked from behind the curtain one last time,

his heart sank at the absence of a single person—Belle da Costa Greene. Curtis had

written her from the road, from Boston, with updates of the reviews and crowds as

the production rolled through Concord, Providence, Manchester and New Haven on the

way to New York. The show was a hit. Capacity crowds! Standing ovations! Rave reviews!

He enclosed tickets—front row, of course—for J. P. Morgan, Miss Greene and any number

in their entourage. On November 15, 1911, the day of the Carnegie show, came a reply

from the librarian: Morgan would be spending the evening with his daughter. “As you

know, it is very difficult to get him to go anywhere,” Greene wrote Curtis at his

hotel.

Yes, of course he knew. Since obtaining the initial financing in 1906, Curtis had

seen very little of Morgan, despite long stays in Manhattan. “He spends his time lunching

with kings or kaisers or buying Raphaels,” said a British patron. The cigar, the top

hat, the cane, the hideous purple nose—Curtis experienced very little of the Morgan

persona after signing his initial deal. The face of the titan, if not the hand that

wrote the checks, was in the person of the enchanting gray-eyed Miss Greene. So, while

Curtis didn’t expect the aging Morgan to trundle uptown on a November night, he held

out hope that the public representative of his patron would be in attendance on the

evening of his highest honor. Earlier that year, he had taken his son Harold to visit

Belle Greene at the Morgan Library. Hal was impressed at the setting and people in

the rich man’s circle who knew and praised his father.