Social: Why Our Brains Are Wired to Connect (6 page)

Read Social: Why Our Brains Are Wired to Connect Online

Authors: Matthew D. Lieberman

Tags: #Psychology, #Social Psychology, #Science, #Life Sciences, #Neuroscience, #Neuropsychology

BOOK: Social: Why Our Brains Are Wired to Connect

4.92Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

Even for chimpanzees, there are a lot of social dynamics at work here.

For Smith, Johnson, and Brown to form the alliances that work best for each of them, they need to keep track of a great deal of social information.

They need to keep track of everyone’s status relative to themselves, but they also need to know the status of each chimpanzee relative to the others.

If there are just 5 chimps in a group, each chimp needs to keep track of the social dynamics of 10 chimp-to-chimp relationships, or

dyads

.

A group of 15 requires keeping track of 100 chimp-to-chimp relationships to be fully informed.

Triple the group size to 45, and now there are 1,000 dyadic relationships.

When we reach Dunbar’s number

, a group of 150 individuals, there are more than 10,000 possible relationship pairs to consider.

So we can begin to see why a bigger brain might come in handy.

While there is a tremendous upside to being part of a group, that is true only if you know how to play the odds and form the right coalitions to avoid the downsides of group living.

It requires an expansive capacity for social knowledge.

The same is true, of course, for humans.

To give an example, every year, thousands of undergraduates apply to the most prestigious PhD programs in the United States.

A big part of getting in is having persuasive letters of recommendation that are sent on one’s behalf.

These letters have been subjected to the same grade inflation forces running rampant across college campuses.

Thus the assessments typically range from “this is a fantastic student” to “this is the

most

fantastic student.”

When I read these letters, what often matters more to me than the content of the letters is who wrote them.

When a fellow social or affective neuroscientist writes a glowing letter, it is highly meaningful to me because that person is accountable to me the next time we are at a conference together.

In contrast, professors in anthropology can write a glowing letter to me with impunity, regardless of any flaws in the candidate, because

I probably don’t know them and they won’t be held accountable.

For this very reason, their letters do not hold as much weight with me.

The upshot of all this is that a college sophomore thinking about which lab to volunteer for will tangibly benefit from knowing how a potential mentor in the department is viewed by the professors the student might want to study under to get a PhD a few years later.

This is complex social cognition.

Many of the important innovations created by human beings—steam engines, lightbulbs, and X-rays—were created by a few individuals whose work was shared with the world at large.

The majority of human beings would not have come up with these solutions in a hundred lifetimes.

I know I wouldn’t have.

Most of us create very little that advances civilization.

But each of us needs to navigate complex social networks to be successful in our personal and our professional lives.

Primate brains have gotten larger in order to have more brain tissue devoted to solving these social problems, so that we can reap the benefits of group living while limiting the costs.

Part Two

Connection

CHAPTER 3

Broken Hearts and Broken Legs

C

omedian Jerry Seinfeld used to tell the following joke: “According to most studies, people’s number one fear is public speaking.

Death is number two.

Does this sound right?

This means to the average person, if you go to a funeral, you’re better-off in the casket than doing the eulogy.”

The joke is a riff based on a privately conducted survey of 2,500 people in 1973 in which

41 percent of respondents indicated that they feared

public speaking and only 19 percent indicated that they feared death.

While this improbable ordering has not been replicated in most other surveys, public speaking is typically high on the list of our deepest fears.

“Top ten” lists of our fears usually fall into three categories: things associated with great physical harm or death, the death or loss of loved ones, and speaking in public.

Of course our fear of physical harm is precisely why we evolved an experience of fear in the first place.

Would-be ancestors who lacked a basic fear of dangerous threats probably never became our ancestors because they did not live long enough to reproduce.

Fearing the loss of loved ones makes evolutionary sense too because they help pass on our genes.

But public speaking?

Darwin didn’t have a lot to say about that one because there is no obvious connection between public speaking and survival.

So what are we afraid of when we think about speaking in public?

We all speak, and most of us are quite comfortable speaking with friends, family, and colleagues.

So it isn’t speaking per se that gives us butterflies.

It’s the public part of

public speaking that terrifies so many of us—whether it’s speaking in front of a dozen, a hundred, or a thousand strangers.

You may have seen some of the same after-school television specials I did growing up.

The sixth grader gets up to give a speech in front of an auditorium filled with other kids.

He flubs his lines and becomes the laughingstock of the school (until he does something unexpectedly brave and wins the heart of the cutest girl in school).

I suspect most of us have a fear that parallels this scene.

We are afraid that everyone will think we are foolish or incompetent.

We are afraid that everyone will reject us.

Indeed, speaking in front of a large audience probably maximizes the number of people who could all reject us at one time.

What is curious is that the person speaking probably doesn’t know or care about most of the people there.

So why does it matter so much what they think?

The answer is that it hurts to be rejected.

Ask yourself what have been the one or two most painful experiences of your life.

Did you think of the physical pain of a broken leg or a really bad fall?

My guess is that at least

one of your most painful experiences involved

what we might call

social pain

—pain of a loved one’s dying, of being dumped by someone you loved, or of experiencing some kind of public humiliation in front of others.

Why do we associate such events with the word

pain

?

When human beings experience threats or damage to their social bonds, the brain responds in much the same way it responds to physical pain.

Birthing Big Brains

Why are our brains built in such a way that a broken heart can feel as painful as a broken leg?

One reason why being rejected hurts so much is that the larger brain was the easiest way for evolution to make us smarter.

Having a larger brain, relative to one’s body size, is instrumental to one species’ being smarter than another species.

And as we discussed, adult humans have a particularly large brain

relative to their body size.

Giving birth to a baby with a big brain is not easy

, as any woman who has given birth can attest.

The rest of the body passes through the birth canal “relatively” easily, but the head can often barely make it out.

Given the shape of the female pelvis, infants have to be born when they are because if the brain were to keep growing, human infants would not be able to be delivered.

The human infant brain is typically only a quarter of its adult size.

That means the great majority of the brain’s development happens after we are born.

It matures as much as is possible in the womb, but this still leaves the lion’s share of developmental work to be done after birth.

The upside to this state of affairs is that our brains are finished being built while they are immersed in a particular culture, allowing our brains to be fine-tuned to operate in that specific environment.

The downside to an immature brain

is that babies are ill equipped to survive on their own.

Human babies are born completely helpless and stay that way for years.

In fact, we have by far the longest period of immaturity of any mammalian species.

(Many parents will be happy to tell you that this period of immaturity lasts well into the twenties!) And

it is true that the human prefrontal cortex

does not finish developing until the third decade of life.

While humans are the mammals born the most immature, all mammals share this characteristic to some degree.

Our tendency to be born with immature neural machinery extends back 250 million years to the very first mammals and this was the first step in making us the social creatures we are today.

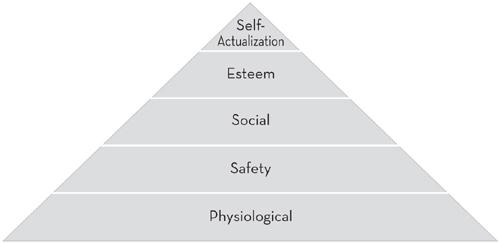

Inverting Maslow

In 1943, Abraham Maslow, a famous New England psychologist

, published a paper in a prestigious journal describing a

hierarchy of needs

in humans.

The hierarchy he identified is typically depicted as layers of a pyramid (see

Figure 3.1

).

Maslow suggested that we work

our way up the pyramid of needs, satisfying the most basic needs first and then, when those are satisfied, moving up to the next set of needs.

Figure 3.1 Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs.

Adapted from Maslow, A. H. (1943). A theory of human motivation.

Psychological Review

, 50(4), 370.

At the bottom of the pyramid are physiological needs like food, water, and sleep.

The next level of the pyramid focuses on our safety needs, such as physical shelter and bodily health.

Physiological and safety needs are really fundamental needs with a capital

N

.

No one can do without them.

The rest of the pyramid consists of “nice if you can get them” needs, or needs with a small

n

.

My son may say he needs another scoop of ice cream, but really he just wants one; he will survive without it (even if he thinks he won’t).

In Maslow’s pyramid, the remaining needs—the extra scoops of ice cream—are love, a sense of belonging, and being esteemed.

Self-actualization

(that is, reaching one’s full potential) is the cherry on top.

Ask people what they need to survive, and there is a very strong probability that they will produce answers from the bottom tiers of the pyramid, like food, water, and shelter.

Infants need food, water, and shelter too.

The difference is that infants have no way of getting

these things for themselves.

They are absolutely useless when it comes to surviving on their own.

What all mammalian infants, from tree shrews to human babies, really need from the moment of birth is a caregiver who is committed to making sure that the infant’s biological needs are met.

If this is true, then Maslow had it wrong.

To get it right, we have to move social needs to the bottom of his pyramid.

Food, water, and shelter are

not

the most basic needs for an infant.

Instead, being socially connected and cared for is paramount.

Without social support, infants will never survive

to become adults who can provide for themselves.

Being socially connected is a need with a capital

N

.

Like the default network in

Chapter 2

, this restructuring of Maslow’s pyramid tells us something critical about “who we are.”

Love and belonging might seem like a convenience we can live without, but our biology is built to thirst for connection because it is linked to our most basic survival needs.

As we will see, connection is the first of three adaptations that support our sophisticated sociality, but our need for connection is the bedrock upon which the others are built.

Pain

A doctor has three patients waiting to see her.

The first patient comes in complaining of a headache.

The doctor says, “Take two Tylenol, and call me in the morning.”

The second patient hobbles in favoring one leg and says, “Doc, I think I sprained my ankle.

What should I do?”

The doctor says, “Take two Tylenol every day, and call me in a week.”

The third patient walks in having difficulty maintaining her composure, and she says, “Doc, I’ve got a broken heart.

What should I do?”

Without missing a beat, the doctor says, “Take two Tylenol every day, and call me in a month.”

True story?

Of course not.

No doctor would prescribe a painkiller to deal with feelings of rejection.

But the story is instructive because our reactions to it reveal our intuitive theory of pain.

Pain is a fascinating phenomenon.

On the one hand, it is very unpleasant, sometimes excruciatingly so.

Yet it is one of the most fundamental adaptations promoting our survival.

Nearly 20 percent of adults live with chronic pain, leading to countless lost workdays and deep depressions.

One recent study estimated that

pain was responsible for over $60 billion

in lost productivity per year within the United States alone.

As awful as chronic pain can be, not feeling pain is far more disastrous.

Children born with congenital insensitivity to pain

are incapable of feeling pain and often die in the first few years of life because they injure themselves relentlessly, often falling victim to deadly infections.

Other books

Tiffany Street by Jerome Weidman

Totem by Jennifer Maruno

Bound (The Divine, Book Four) by Forbes, M.R.

One Night in Weaver... by Allison Leigh

RACE AMAZON: False Dawn (James Pace novels Book 1) by Andy Lucas

The New Elvis by Wyborn Senna

Some Kind of Peace by Camilla Grebe, Åsa Träff

Rhys by Adrienne Bell

Ambition's Queen: A Novel of Tudor England by V. E. Lynne