Something's Rising: Appalachians Fighting Mountaintop Removal (28 page)

Read Something's Rising: Appalachians Fighting Mountaintop Removal Online

Authors: Silas House and Jason Howard

Anne:

I was talking to some kids at the library the other day about this folktale we had read. And the king in the story thought everything in the world belonged to him. So I asked the children who they thought the world belonged to and one said, “Everybody.” One said, “All of us.” One said, “Nobody.” Another one said, “God.” Not a one of them said, “Whoever's got the deed.” I mean, in a way, it is just a piece of paper. And as a landowner, as a human being, you have some responsibility to the people who will be here after you.

Lynne:

Morally and legally, don't we have a duty to protect children and things that can't protect themselves? I see the land as one of those things. The land deserves protection. The industry wants to put out that we want to stop building of the roads and development and all that. We don't. We just want to stop rampant devastation of the land. The industry has already been allowed so much.

Anne:

Even looking at it selfishly, it's really in our own interest to protect it. “Never send to know for whom the bell tolls”—because we cut ourselves off from the earth at our own peril. We're part of that, and we tend to ignore that for some reason.

Lynne:

We're taking thirty pieces of silver for our homeland.

Anne:

You know, it did surprise me when the press ignored us going up there to Frankfort and how big a crowd we had.

15

I would've thought the press and the state government would have at least

tried

to be neutral.

Lynne:

They never even tried to

appear

neutral. I felt rejected by the government when that happened. It seems like they're awfully careful to not hurt the industry's feelings, and the industry—well,

they are so sensitive that anyone would challenge them on the necessity for mountaintop removal.

Anne:

The governor even came out to talk to them, when the mining industry people went up there about a month later. And the lieutenant governor, too, came out and expressed his opposition to the Stream Saver bill.

Lynne:

But you know, that didn't surprise me, that so many miners went up there with them. Because if my boss told me to go somewhere like that and lobby, I probably would, too.

Anne:

Especially if they told you that you had the day off and you better go and they said what time the bus would be there to pick you up. Everybody knows that's what happened.

Lynne:

Yeah, so you'd think that the governor and the papers would know it, too.

Anne:

Well, I think part of it is the overall political atmosphere now, it's so conservative. If you are even moderately challenging something, they portray you as an extremist nut. And the press now, they seem to have this idea that the truth is somewhere in the middle between the extreme somewhere. Every time we say something, they have to give Bill Caylor a chance to respond. And sometimes the truth just

is not

in the middle. Sometimes the truth is on one side only. But they're not doing any investigative reporting enough to know this. They put stuff in that we write and they put stuff in that industry people write, but that's not the same as covering an issue.

Lynne:

Can you imagine if they'd been concerned with giving equal coverage to both sides of the Holocaust?

Anne:

Or slavery!

Lynne:

Not that mountaintop removal is necessarily comparable to those two things, but the point is that it's an important issue that needs newspapers to step up and take a side on it. Let's have Kentucky open for business and commerce—that's all they care about. The newspapers and big business seem to be awful good bed buddies. Sustainable agriculture used to be part of the team, but now that's all out. It's just

energy and money that's important to them. So we all just feel like ugly stepchildren.

Anne:

And as the price of coal goes up it doesn't bode well.

Lynne:

They take advantage of the ignorance people have about the coal-to-liquid issue, or how people don't know how widespread mountaintop removal is.

Anne:

You know, I've heard so many stories from people who live around these mountaintop removal sites. Their stories were so awful, so disturbing, so moving. What it's like to live with that all the time. Their rights are being violated so terribly, their quality of life is being ruined by the dust and noise. Their foundations being cracked and the water being ruined. And I've never seen coverage of that—no kind of investigative reporting about that. Now in the seventies that would have been covered by the press in Eastern Kentucky. The press covered all these issues back during the fight against the broad-form deed, and we heard from the people who were opposed to that. And we're just not hearing that about mountaintop removal. There's been some kind of shift in the press; they seem to be more complicit now and to serve the purposes of the coal industry in a way they really didn't before. But it reminds me of in the thirties, when the local law enforcement and the coal companies were so helpful to one another.

Lynne:

I think the coal industry is more willing now to stretch their story, too, to go on about how they're doing the greater good and helping people. Back when the political climate was more liberal they weren't able to do that as easily. And I just don't believe they were as underhanded back then, either.

Anne:

It's interesting, it's funny even, how they'll sometimes acknowledge the bloody and shameful history of coal in Appalachia. They'll say, “This isn't your grandfather's coal company.”

16

That's one of their mottos. It's like they're saying, “Yeah, it's true that we lied and did all kinds of things in the past, but just give us another chance, just trust us.”

Lynne:

“Yeah, we're on the right track now, we'll do right now.”

Anne:

They'll say they're only going to take 7 percent of the mountains. But we're never told 7 percent of

what

. And they expect us to believe that they're going to mine that 7 percent and just up and quit. Then we can just trust them to stop, no matter what the price of coal is.

Lynne:

“It's over now, we'll see you. Bye.” That's not going to happen.

Anne:

There's a reason why we don't believe them. Because we know the history—the very complicated and troubled history of coal in Kentucky—we have to question their motives.

Lynne:

Somebody started attacking me the other day. They said, “Oh, so you don't benefit from coal-mining, you don't use electricity.” I was so hurt and flustered that I just kindly limped away, but I've used electricity all my life and we didn't have to have mountaintop removal for that, and we still don't.

Anne:

It's not right here yet, and I'm glad, but when I came back from seeing where it is—which is not far away at all

17

—those images stuck with me. I couldn't get them out of my head, I couldn't help but imagine it. And I could not stand the thought of it being here. I couldn't. I think that would be a loss that would be—

Lynne:

—unbearable—

Anne:

Yeah, I believe it would be. I know people bear all kinds of things, and I guess one could bear it, but it would be an irrevocable loss. And I'm not immune from that. This place is very much like other places where mountaintop removal has happened. Where I've seen it up close is in Perry County. I used to live there. I know some of those communities that are totally gone now. Like Lost Creek. People lived there. And now I can't imagine that there's any form of life there and never will be again. It's like my love of this place, and thinking of it happening here, that makes me want to fight it. Because I don't want it to happen to anybody else's place, either.

Lynne:

I think I'm speaking out because I've feared it happening too close. I think of families going through it. As I grow

older, I see the government is failing, it seems to me, very badly. I'm seeing that the coal industry has a strong hold on government and public opinion, and that makes me mad. And I do think people are not aware of the scale of damage. I feel like we're at a desperate time, at a time that we need to plead the case to people who would care if they had the time to understand and had the information. The whole practice evokes a danger and a senselessness to me. It's not practical and necessary like they say. It's being done out of callousness and carelessness and detachment from farming, from the land, from rural people. There's more and more money to be made with bigger and bigger machines. It's all business interests, and none of them want to take responsibility for what's happening to our mountains. It's a big network of people who don't want to claim what they're doing right beside their own granny's place.

Anne:

I believe you're right.

Lynne:

We have so much a corporate society, and that makes me want to speak out. Corporations operate mines, and the little people who live in the war-torn country or in the ravaged mining country, I feel like we need to stay alive as long as we can and have a voice and at least say, “We don't want this to happen. Why did you do it?” Our country's kind of getting away from us. We're so corporate and so money-hungry. We end up hurting the land and hurting the people.

Anne:

And the same corporations that are bringing us the war and mountaintop removal, they also lull us into complacency through all kinds of entertainment that we have. That entertainment, a lot of the time, shows us that people who speak out are kind of flaky. And that the heroes are people who just make money, are part of the corporate culture and are very attractive and pleasant. It's all of a piece.

Lynne:

We see something as horrible as war—we thought that when Bush started the war we weren't going to be there long, we were told that they were so happy we were there; and now look, it's been seven years. And now, now what? And we're still at war.

And think about the way they talk about mountaintop removal: “It's only going to be 7 percent and we'll have so much electricity. Just bear with us.” And we just end up with an old golf course that nobody wants to go to.

Anne:

If I could talk to all my neighbors, I would appeal to what I know is their love of the land and their respect for all the people who lived here before them. I'd try to make that connection for them so they wouldn't perceive mountaintop removal as just something on the news, something they thought of as people being up in arms about without themselves wanting to get involved. I would ask them, “Do you want to see that mountain there blown up and destroyed? Do you want to see that creek full of rocks from the mountain? Or the river down here full of sediment, empty of fish?” It makes it different when you think about it happening to your own land.

Lynne:

I'd try to remind them to remember their heritage, their families, how their ancestors worked these hillsides, walked these mountains. I'd encourage them to visualize their parents and their grandparents standing around on these mountains with their hoes and fiddles and mules, saying, “Now you all need to stop this.” Because I truly believe they

would

say that.

Teges Creek, Clay County, Kentucky, May 6, 2008

The Gathering Storm

Now the rich, they get richer, and the poor mine the coal

And the lights must keep burning the cities we're told

But where will we turn to when the boom turns to bust

And the once-living mountains turn to rockpiles and dust

—Anne Shelby, “All That We Have”

The road over Black Mountain winds about like a coiled snake, poised to strike at any moment. At 4,145 feet above sea level, Black Mountain is one of Appalachia's highest mountains. The view from crooked Highway 160 is nothing less than breathtaking on this July evening as a storm front moves in on over the Cumberland Plateau in Harlan County, Kentucky. The seemingly endless acres of trees are dark green beneath the graying sky, a pristine forest that seems untouched by humanity. From up here this looks like a wild, primal land.

After dozens of stomach-churning curves, a small sign announces that the Virginia state line has been crossed. And suddenly, everything changes. Now there is a moonscape below, a barren wasteland of dirt and exposed rocks and yellow bulldozers. From near the summit of Black Mountain can be seen a mountaintop removal site that stretches itself brazenly above the town of Appalachia, Virginia, and it looks like a scar on the face of the earth.

The Kentucky side of Black Mountain was saved, thanks to the public outcry that followed when it became known that a coal company was seeking a permit for mountaintop removal mining on the Commonwealth's highest peak.

1

Things are different on the Virginia side. There the mountain is mostly owned by Penn Virginia, a huge corporation based in Philadelphia that routinely leases out land to coal companies. The mineral rights to these border-straddling mountains were bought up by such corporations as far back as the 1890s.

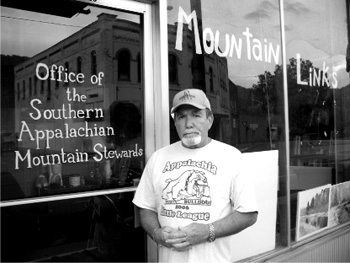

Larry Bush, Appalachia, Virginia. Photo by Silas House.

Where once there was a mountain here in Virginia, now there is a deep, dead hole. Even far past the mine, coal dust and dirt cover the huge kudzu leaves that crowd close to the road. The kudzu has crept onto the houses and trailers, too, as if this place is being devoured by two nonnatives: a plant from Japan and corporations from a place that locals call “Off,” a land whose inhabitants don't have to see the damage they're doing, or just don't care.

The road rolls on, through the little community of Inman, the site of one of the most tragic chapters in the history of mountaintop removal. It was here on August 20, 2004, at 2:31 a.m., that a boulder weighing half a ton crashed through the side of a double-wide trailer and two interior walls and rolled over the bed of three-year-old Jeremy Davidson, killing him. The rock went on to rip through two more interior walls and finally came to rest against his older brother Zack's bed. The boulder had been dislodged by a bulldozer that had been operating illegally to widen a road for eighteen-wheel coal trucks on a mine site above the family's house.

2

Today, the empty lot beside the Looney Creek Memorial Baptist Church, where the Davidsons' double-wide used to sit, is being overtaken by weeds and kudzu. It is haunted by silence on this Sunday, even though most days people in Inman never get a moment's peace because of the constant roar of machinery that is slowly eating away the ridge above.

The eerie silence is punctuated by a burned-out trailer home, an abandoned tricycle in the ditch, and a young woman—her shoulders tired, her face hollow—walking down the road with a baby on her hip. She considers the passing car and then eyes the sky, watching for rain. The gathering storm has moved on to unleash itself elsewhere for the moment, leaving behind the gray clouds that are a disconcerting mix with the humidity seeping out of the woods.

After a turn onto the Virginia Coal Heritage Highway, suddenly there is the town of Appalachia. Past the North Fork of the Powell River, Appalachia's downtown spreads itself out over a couple of gentle slopes, divided by the railroad that was once the lifeblood of the town. Appalachia used to be a boom town, back when there was plenty of underground mining work. In the early 1900s it took on the nickname of “Mineralville” because of its wealth of coal.

But nowadays Appalachia looks like a dying town. Despite the fact that Virginia's seven coal-producing counties pump out more than forty million tons of coal a year, they remain among the state's poorest. In Wise County, for example, about 19 percent of people live below the poverty level, nearly double the Virginia state average of about 9 percent.

3

Along Main Street one of the buildings has been completely hollowed out, leaving the shell of a once-elegant brick store; now, weeds grow between the cracks in the floor. There is Appalachian Towers, where a group of elderly people sit out front on benches, smoking cigarettes and cracking jokes. Past this is another storefront, which is being used as storage. Through the dirty windows can be seen stacks of boxes. On the corner a large banner from the Appalachia First Baptist Church announces Vacation Bible School and announces not only that “Kids 'R' Kool” but also that “Jesus Rocks.” There is the Miners Exchange Bank—its logo a filled coal car with pick and shovel—but close by is another empty building. Built to curve with the street, this was once a beauty, with decorative brickwork and rounded windows. But now most of the windows have been painted over and some are broken; in one an armless mannequin of a little boy peers out, staring maliciously into the eyes of anyone passing on the sidewalk below.

Just across the street is the local chapter of the United Mine Workers and beside it, Mountain Links, the office of the Southern Appalachian Mountain Stewards (SAMS). Inside, the light is dingy and the air smells of damp carpet. The office furniture looks as if it has been donated just to escape the dumpster. On a

desk sits a vase full of dead tiger lilies, their brown petals littering the desktop. Despite the dreary conditions, SAMS has established this storefront on Main Street as a symbolic measure as much as a literal one. It's important for people passing by to see that someone is on their side. It's well known here that most people are against mountaintop removal. They just don't want anyone to know it.

Larry Bush, however, doesn't care who knows it. In fact, he wants everyone to know that he's on the warpath to stop what he calls “a crime,” and as chairman of SAMS, he doesn't fail to announce that every chance he gets.

Bush got involved with SAMS because he was tired of witnessing what he calls “the daily rape” of the mountains he has loved all of his life. Before his life was overtaken by activism, Bush served a tour of duty in Vietnam and worked as an underground miner for twelve years and as a federal mine inspector with the Mine Safety and Health Administration (MSHA) for over thirteen years. Clearly, he knows what he's talking about. His presence makes this known, too. Bush does everything with an air of defiance. It's in his walk, his firm handshake, the serious scowl that stretches over his face when he talks about the issue.

Yet there is also a humility and vulnerability about him that is reassuring. Although he speaks from experience and wisdom, he sometimes grows so frustrated that he shakes his head and mutters, “Lord have mercy, children,” reminding the listener that he's in this fight because he doesn't see any way around

not

being in it. He's committed to the fight and to SAMS.

Based in Wise County, Virginia, SAMS was started by Pete Ramey, a former miner and war hero who lived near a mountaintop removal site at Roda, also in Wise County, and Pat Jervis, a former schoolteacher from Appalachia. After his house was pummeled with rocks from the blasting, Ramey filed complaints with the Division of Mine Land Reclamation (DMLR). When his complaints went unheard, Ramey filed suit against the company. The coal company countersued, accusing him of defamation.

4

Ramey and Jervis responded by forming SAMS.

Since then, the organization has grown to include over 130 members in Southwest Virginia, and has joined forces with other, larger groups, including the Alliance for Appalachia—a coalition of thirteen organizations—and other groups on the East Coast that are fighting against environmental devastation and seeking solutions in energy resources.

5

SAMS found its central fight—and Bush found his most trying struggle yet—when Dominion Virginia Power announced that they were going to build a “clean coal”-burning power plant in Wise County, at St. Paul, about fifty miles from Bush's home.

“First of all, there's no such thing as clean coal,” Bush says, adjusting his baseball cap, something he often does when he's frustrated. “Clean coal is a myth because there's so much in it. They can't take all that out. If they could they wouldn't because it'd be too expensive. For anyone to get out there and tell you—like these commercials you see, talking about ‘clean coal'—why, there's no such thing. Once they put it out there, it's subliminal. After a while people say ‘Well, maybe it is clean.' We're so gullible, it's a damn shame.”

The operation in St. Paul, formally known as the Virginia City Hybrid Energy Center, would be a 585-megawatt, $1.8 billion coal-fired power plant run by Dominion, Virginia's largest energy company, with 2.3 million customers in the state. According to the

Washington Post

, “Dominion refers to the facility as a hybrid because it will be engineered to burn coal, plant matter, and ‘gob,' a kind of mine waste made of rock and coal that is piled around the mining districts of southwest Virginia.”

6

Bush and the other members of SAMS have been joined in the fight by people from outside of the region. Dozens of people from northern Virginia, to which 70 percent of the plant's electricity would go (the rest going to North Carolina), have testified in opposition to the plant. In March 2008, a group of Virginia religious leaders banded together to release a statement calling the use of coal-fired electric plants “immoral and destructive.”

Protesters from throughout the state immediately converged on the office of Governor Tim Kaine. The following month, three activists chained themselves together to block the entrance to Dominion's headquarters. They remained in the road for about ninety minutes before being dragged away by police, who gave them a ticket for blocking traffic.

In June 2008, only two days before Dominion was to break ground on the plant, twelve protesters—most of whom were students from James Madison University and Virginia Tech—were arrested in Richmond, Virginia, after they blocked Tredegar Street at the headquarters of Dominion. Four of the activists had encased their hands in fifty-five-gallon drums of cement; another dangled from a pedestrian footbridge in a climber's harness for more than two hours. Nicknamed “the Tredegar Twelve,” the group eventually accepted a plea bargain to do 200 hours of community service in Richmond to avoid serving jail time.

Conservationists are especially concerned over how the plant will affect the air quality of two national parks that are relatively nearby: the Shenandoah National Park and the Great Smoky Mountains National Park.

“The air quality in the Smokies is already degraded considerably,” Don Barger, senior regional director for the National Parks Conservation Association, told the

Bristol Herald Courier

after plans for the plant were announced. “This would exacerbate the problem…in a situation that is really overloaded and that we are trying to clean up.”

7

SAMS has been especially active in the fight against the Dominion plant, organizing a petition against the power plant that has been signed by more than 43,000 people. The petition was the brainchild of Kathy Selvage, vice-chair of the organization. Bush and other members of SAMS have also lobbied in Washington, D.C., and have spoken at hearings throughout the country to help stop the power plant and mountaintop removal.

Dominion has replied to the outcry by running a multimillion-dollar publicity campaign that includes print, radio, and

television spots emphasizing how the plant will benefit everyone, including the people of southwest Virginia.

Unfortunately, coal companies and their miners have not responded with as much diplomacy. Bush and his family have repeatedly been the victims of threats, obscene phone calls, and harassment.

“A guy blocked me in with a coal truck. I's setting on the side of the truck and he come right up against the door of my truck where I couldn't get out. When I'm coming out of the holler they cross the double lines to crowd me into the creek. They know me and my truck,” Bush says, but his defiance seems to bloom instead of be cowed by the harassment.

The only thing that really worries Bush is that someone will hurt one of his three grandchildren or his two daughters.

“I take the oldest grandbaby to school every morning,” he says. “It worries me because they crowd me, they come across the road. If one of them ever wreck me and make me hurt one of my grandkids, he's a dead son-of-a-bitch if I can live long enough to get to him. If they ever hit me, they better kill me, 'cause if I've got an ounce of breath in me, if I can get up, I'll kill

them.”