Southern Storm (44 page)

Authors: Noah Andre Trudeau

Eight miles on the flying column approached Rocky Creek, behind which Confederate General Wheeler was waiting with some of his men. The fight for the crossing unfolded in two short phases. In the first, Kilpatrick’s cavalry cleared the Rebel outposts away from the creek’s south side. These advance posts existed solely to sound the

warning, so the Southern riders wasted little time getting across when challenged. “We made them fly,” boasted a Pennsylvania trooper.

Phase two was a little trickier, since General Baird was careful with his men’s lives. After probing the length of Wheeler’s line and locating an undefended stretch, Blair sent one regiment across Rocky Creek. Once over, the unit—the 74th Indiana—immediately made its presence known to Wheeler, who, finding his line breached, pulled back toward Waynesboro. In Major Connolly’s words, the Rebs “lit out.”

Several of Kilpatrick’s regiments charged across the creek to hurry the Rebels along. They brought back with them a wounded Texan who under interrogation admitted that everyone was expecting an attack on Augusta. “He also told us that there was no rebel infantry outside of Augusta, and that Wheeler’s cavalry was scattered all over the country,” reported Connolly.

The combined column pressed forward a mile to a crossroads where generals Baird and Kilpatrick argued about the next move—Kilpatrick wanting to follow the most direct route to Waynesboro, Baird preferring to swing below it in order to establish contact with the middle columns coming toward them from Birdsville. Since Baird was senior, his opinion prevailed, so everyone jogged a short distance south before setting up for the night. “If we get any communication from the rest of our Corps tomorrow we

may

turn toward Augusta again,” observed Major Connolly.

*

Sherman’s headquarters tent for this night was located on the west bank of Buckhead Creek, just outside Millen. After tending to his duties, Major Hitchcock came upon the General engaged in a lively conversation (“wish I could note it,” said the aide) with five or six black men, who let one of their number do most of the talking. They had reasoned through the question of whether or not to accompany the Union army and had concluded it would be better for them to stay put. Sherman endorsed their decision, and was clearly impressed by the insight shown by the group’s spokesman.

The elder slave displayed his knowledge of African-American history by citing the military service performed by blacks for General Andrew Jackson at New Orleans in the War of 1812. Sherman men

tioned that the Rebel president had announced his intention to arm the slaves to help the Confederacy. If Jefferson Davis went ahead with his plan, Sherman wondered aloud, would blacks fight against the Union? “No, Sir,” said the spokesman with emphasis, “de day dey gives us arms,

dat day de war ends!

”

When he wasn’t chatting with his black visitors, Sherman was making some key decisions regarding the campaign’s ultimate objective. To Major General Henry W. Slocum of the Left Wing, Sherman designated a pair of roads to be used by the Fourteenth and Twentieth corps in order to “continue to march toward Savannah.” General Kilpatrick, he told Slocum, “will be instructed to confer with you and cover your rear.”

Major General Oliver O. Howard also learned for certain that the

“next movement will be on Savannah.” He was to keep the Fifteenth Corps marching along the west side of the Ogeechee River, as the Seventeenth was to continue to chew up the railroad along the opposite bank. Sherman, believing that the Confederate leadership remained uncertain whether he intended to strike for Macon, Augusta, or Savannah, authorized Howard, if feasible, to send raiding parties well south of Savannah to disrupt the rail links with lower Georgia and Florida. Speed was now becoming a watchword. Sherman remarked on the Savannah garrison: “The fewer the men and the sooner the party starts the better.”

S

ATURDAY

, D

ECEMBER

3, 1864

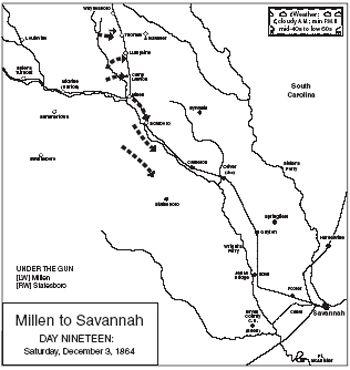

An American eagle of a military bent, loitering high over the confluence of the Ogeechee River and Buckhead Creek, would have observed a decided, even decisive, change in the direction of Storm Sherman. Fully three-quarters of his force was either now committed or in the process of being committed to roads that led unerringly to the south and east—toward Savannah. The course so clearly delineated ran along a peninsula-like corridor, bounded to the east by the Savannah River and to the west by the Ogeechee. Into this region Sherman now steered three infantry corps and his cavalry division.

Both flanks were protected by difficult-to-cross water systems, which provided the principal tactical advantage of this movement. The main disadvantage was that Sherman was clearly showing his hand, so his enemy, who had been stumbling and struggling to pin down his front, would soon know precisely where to find it. The closer to Savannah Sherman’s columns marched, the more the land became favorable to the defense. The number of swamps and swampy streams increased to the point where moving the wagons was limited to narrow strips of built-up roadways, making a situation ideal for delaying actions.

It was partially to offset this defensive advantage that Sherman kept one corps moving along the southwest bank of the Ogeechee, ready to turn any line of resistance the Confederates might try to establish. An almost textbook example of this plan working was provided this day by Confederate Major General Henry C. Wayne, who was nervously monitoring the Federal movements in person. On December 2 Wayne retreated from Station No. 7, Scarboro, to No. 4½, in the area

of modern Oliver. There, at the junction of the Ogeechee River and Ogeechee Creek, Wayne was joined by several militia units under Colonel Robert Toombs,

*

forwarded from Savannah. About 10:30

A.M

., after receiving a briefing about the advances of the Union Fifteenth Corps along the Ogeechee’s opposite bank, Wayne recognized that this column “would cut my rear,” so he conferred with Colonel Toombs. They agreed on a strategic withdrawal of approximately twenty-seven miles, to Station No. 2, Eden.

Sitting in Savannah with his maps spread before him, Lieutenant General Hardee realized at once that Wayne’s precipitate maneuver ceded a strong defensive position behind Ogeechee Creek, so when the militiaman arrived at Eden, he was met by one of the general’s staff officers “with instructions to return to No. 4½, and that further re-enforcements would be sent to me. Obeyed the instructions, though in opposition to my own judgment and that of my officers, and reoccupied No. 4½ about 7

P.M

.,” Wayne reported. Sherman could read maps as well as Hardee. Even though he had no knowledge of Wayne’s back-and-forth actions, he saw the same potential at Station No. 4½ as did his opposite number. He pointed it out today to Major Hitchcock, commenting: “There we must cross a creek and there they have the shortest line to hold from river to river.” Added the aide: “Perhaps we shall fight them then—

perhaps not.

”

Overall, the General was well satisfied, with one or two caveats. As he later related, “the whole army was in good position and in good condition. We had largely subsisted on the country; our wagons were full of forage and provisions; but, as we approached the sea-coast, the country became more sandy and barren, and food became more scarce; still, with little or no loss, we had traveled two-thirds of our distance, and I concluded to push on for Savannah.”

The marches made by the Fifteenth Corps, south of the Ogeechee, had positioned its columns roughly opposite Millen and Scarboro, points only just reached today by units on the north side, so for many of Major General Osterhaus’s men this was a day of rest. Clothes washing figured in several diary agendas, as did bathing in the river and some of its tributaries. “There was a forage party sent out, they brought

in pork, potatoes, & corn and fodder,” recorded a journal keeper in the 63rd Illinois. The history of the 53rd Ohio noted the discovery of a citizen who secreted himself underground with his goods. “He was buried with his valuables,” recounts the history, “but the sharp nose of the Union boys discovered the ‘stiff’ and brought it to the surface, together with the valuables. It was amusing to see the foragers going around prodding the ground with their ramrods or bayonets, seeking for soft spots, and when such were struck, they soon found a shovel to see what was buried beneath.”

The exceptions to this pattern were two brigades—one each from the First and Fourth divisions—sent across the Ogeechee on the pontoon bridge to wreck the railroad between Millen and Scarboro. Viewing the railway route outlined by pyres of burning ties, an Illinois man reflected, “How terrible the sweep of an unchecked army!” The Fifteenth Corps brigades joined with others from the Seventeenth on the same mission. “At Millen there was a junction, one branch to Augusta, the other to Savannah,” reported a Wisconsin soldier. “We tore up the junction, burned the depot and five large buildings that were used for prisoners.” “Broke camp at daylight,” contributed a comrade in the 10th Illinois, “moved down railroad three miles and tear up, burn and twist—twenty eight rails first…, forty rails second time.”

North of Millen, the roads followed by the Twentieth Corps took its columns to an intersection with the branch rail line between Millen and Augusta, just outside the former, where the men did what by now came naturally. “Having stacked arms and posted pickets, some distance from the [rail]road, we went to work; half of the regiment remaining at our arms, while the other half was at the work of destruction. As soon as a few rods of the road had been destroyed, the party at work was relieved by the party guarding the arms. Fence rails were set afire and the iron rails laid across, whereby the latter soon became bent and unserviceable. The road had been repaired by the rebels but a few days before, as we saw from the newly made ditches on both sides of the track, not supposing that we would be there so soon.”

The course followed by the Twentieth Corps brought many of its units near enough to Camp Lawton that curious soldiers flocked to the place like tourists to a popular attraction, though the images they recorded were anything but pleasant ones.

Samuel Storrow, 2nd Massachusetts

Visited the Stockades where the Rebels confined our prisoners. The one we saw was 450 or 500 yards square on a gentle slope with a brook at the bottom. On the hill opposite was a fort which commanded the whole of the interior of the Stockade, within easy grape range.

*

The stockade was of pine logs a foot thick & 20 feet high, with sentry boxes perched on top & outside…. A slight railing ran all the way around about 25 feet from the stockade; this was the “dead line;” any man crossing or leaning on this was liable to be shot without any warning.

John Potter, 101st Illinois

The prisoners were compelled to erect houses or sheds for their own shelter. The material was soon all worked up and the later arrivals could not do any better than to scoop holes in the sand, and many of them died and were left, as it were, actually in graves of their own digging.

George S. Bradley, 22nd Wisconsin

The huts were built in all manner of shapes. Some had walls of logs, with a covering of timber, and over these a good layer of sand. Some had walls of turf, again others were cut into the ground perhaps two feet and then covered, sometimes with pine slabs, sometimes with sand, and some were simply thatched with pine boughs, while others were bare sheds. It made my heart ache to look upon such miserable hovels, hardly fit for our swine to live in, and here our brave soldiers had to stay.

Rice C. Bull, 123rd New York

There was not a soul around the place when we arrived and the only things left were a few dirty, filthy-looking rags. Not a long distance from the prison I was amazed to see the largest spring I ever saw; from it gushed a stream that would be called a small river in the North…, the stream from the spring ran near the stockade and I think furnished water for the prison; if so, they had at least good water.

Peter K. Arnold, 28th Pennsylvania

We saw one of the stockades where they had kept our prisoners. Many was the curse that was recorded against the Rebels by our troops on that day.