Southern Storm (48 page)

Authors: Noah Andre Trudeau

In Richmond, the December 5 issue of one of the city’s dailies, the

Sentinel,

offered an upbeat analysis of events in Georgia. “Sherman’s campaign, which was daringly conceived, has been timidly prosecuted,” it announced. The writers pointed to the slow pace plus numerous delays that had marked the operation thus far. “It has given us time to concentrate our means of resistance and to obstruct his path with daily increasing obstacles. SHERMAN seems to have realized his peril, and to be concerned now only to make his escape. The hero has turned fugitive.” While the government may not have embraced every conclusion reached by the newspaper’s editors, there was a guarded optimism coursing through the War Department. “We are…hopeful of the defeat of Sherman—a little delay on his part will render it pretty certain,” wrote a clerk in a position to hear all that his bosses were hear

ing. However, unlike those running things, the clerk was left with a nagging question: “If it should occur, will it give us peace?” he wondered.

T

UESDAY

, D

ECEMBER

6, 1864

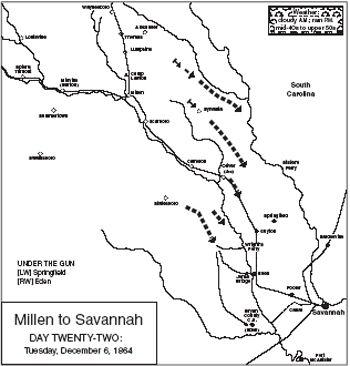

Left Wing

The bulk of Sherman’s forces continued to press along the peninsula formed by the Savannah and Ogeechee rivers leading to Savannah. The Twentieth Corps, operating in the center, reached a spot about twelve miles northwest of Springfield, while the Fourteenth Corps,

running about a day behind on the outside flank, followed the Augusta Road, which wriggled along the Savannah River. The tails of both columns were now being screened by Kilpatrick’s cavalry, with his First Brigade tasked with watching over Brigadier General Williams’s men, while the Second Brigade held its place behind Brevet Major General Davis’s columns.

Everyone was reporting an increasing number of obstructed roadways. There was little rhyme or reason in these efforts to stymie the Federal movements. In some stretches the Rebel activity was a momentary nuisance. “Before going into camp [we] ran into a place where the enemy had felled about 2 acres of timber to prevent our progress,” recorded a New Jersey officer, “and it was just so much time thrown away for our pioneer corps removes it about as rapidly as they can walk.” In other places, the Confederate blockages were more significant. “Were delayed much during the day by obstructions placed in the roads by the enemy,” complained a New York officer. In no case, however, did the delays result in any column not reaching its assigned objective. A major factor in this achievement was the absence of any opposition to the unarmed pioneer squads sent to clear the routes. “There is nothing new in the military line,” declared the New Jersey officer, “we don’t meet any rebels behind every fence and bush dying on behalf of their altars and homes.”

Which is not to say that there weren’t any encounters with the locals. “Stopped at the home of a woman whose son is in our Army & her husband a Confed[erate] Soldier,” wrote a Michigan diarist. In another incident, an Illinois soldier arrived on the scene after a property owner had fled after firing on a forager, then abandoning his house with four women inside. The deed had been done, the residence was forfeit—no pleading could overturn that judgment—but several sympathetic soldiers managed to delay the arson long enough for the women to resettle themselves nearby. One of those men who spoke with the ladies reflected that a “woman under such a trying ordeal [does her] talking with a pathos that is truly eloquent.”

Food gathering went well, though the variety left something to be desired. “Yam, yam, yam,” grumbled an Illinois boy. “Confound the yams.” An Illinois officer declared that “the worst of swamp water [was] enough to kill the devil himself was he compelled to drink it, but by boiling it making coffee strong the wigglers and other vermin

were destroyed.” More critical to this day’s progress were the swamps, increasing both in number and size. When the officer commanding the Second Division, Twentieth Corps, bumped into the wagons belonging to the Third Division, he found the procession stopped “waiting for a long swamp to be corduroyed.” No one else seemed interested in clearing the way, so the officer assigned “a portion of my command at working, giving my personal superintendence until it was finished at dark.”

By now the men moving with this wing were becoming increasingly certain of their objective. “We are on what is known as the middle road to Savannah,” recorded a New Yorker, “which city, the rank and file have concluded, is our destination.” “I got a rebel paper…,” recorded a journal keeper in the 75th Indiana, “it…says Sherman is trying to get to Savannah and I am thankful for the information as I did not know before where we were going.” Nevertheless, Major General Sherman was still determined to keep the enemy guessing. His instructions today to Brigadier General Kilpatrick included orders for him to send detachments to several Savannah River fords, where they were to “make a good deal of smoke and fuss…as though threatening to cross into South Carolina.”

The cavalry commander, still waiting on word from Sherman concerning his request for more horses, took matters into his own hands by allowing parties of dismounted troopers to cross the Savannah River in small boats to search for them. Yet, even as these efforts were under way, another squad of troopers was handed the onerous job of dispatching animals no longer able to keep up. It was especially hard on one Ohio cavalryman, whose horse had been a faithful companion since leaving Atlanta. Now it was clubbed down with thirteen other unfortunate beasts. The column moved on and had covered several miles when, to the trooper’s amazement, the ever faithful steed, his head “covered with blood, and the brains…oozing out from his broken skull,” rejoined the procession. No one could bring himself to shoot the creature, who gamely hobbled along until the bivouac was reached, where he finally expired. “He belongs to the long roll of forgotten heroes,” eulogized the cavalryman.

Kilpatrick’s headquarters this night were at the home of a Captain Brown, where, it was said, George Washington had slept. An officer with the Fourteenth Corps’ rear guard listened with bemusement as the cavalry officer informed the mistress of the house “that her chil

dren could say in after years that Kilpatrick had stayed there.” Not to be outdone, the woman retorted that “Washington was father to his country while [Kilpatrick]…was a desolator.”

Right Wing

Major General Oliver O. Howard’s command continued its bifurcated mission. One corps, the Seventeenth, remained yoked to the Twentieth and the Fourteenth by marching down the right side of the Savannah corridor, following the Central of Georgia Railroad. The command made only short marches this day, with Sherman’s headquarters near Station No. 4½ not moving at all. “There is a considerable washing and cleaning up being done,” recorded an Iowa diarist, “and considerable gambling too.”

It was an enduring part of army life that even on rest periods, someone would get the short end of the stick. It fell to a couple of brigades to spend today railroad wrecking, an assignment putting several units on a reverse course. “As we are performing our retrograde movement, we are accosted with numerous interrogatories as to our destination and the object to be achieved, which elicited numerous witty replies,” contributed a wordy Illinois soldier.

Foragers could no longer count on having a successful expedition. Some efforts met with no problems, procuring “plenty of sweet potatoes and fresh pork,” while others returned empty-handed, leading a few to worry for the first time about the “danger of having to go hungry.” Yet again, efforts by civilians to conceal their valuables were undone by what one soldier called “the inevitable Yankee.”

Throughout this entire operation, Sherman had shown a marked disinclination to stray from the line of march. This day was no exception, with the General content to spend it at his headquarters issuing orders or reading reports. He continued to bring the pieces of his expedition closer together. “I have been dividing my army so long as I knew there could be no serious opposition to either column,” he explained to Major Hitchcock, “now that they must make whatever opposition they can, I concentrate; tomorrow all my columns will be within sound of cannon and in supporting distance.”

Kilpatrick’s Waynesboro report reached Sherman while he was

here, along with his request for more horses. Sherman promptly shot off a circular to his corps commanders instructing each to gather “100 horses, the best adapted to cavalry uses, together with a sufficient number of mounted negroes to lead them…for delivery to the cavalry command of General Kilpatrick.” In a follow-up message to his mounted chief, Sherman vowed that “in order to keep you well mounted” he was fully prepared to “dismount every person connected with the infantry not necessary for its efficient service, and take team horses, even if the wagons and contents have to be burned.”

Among today’s visitors to Sherman’s headquarters was George N. Barnard, a civilian photographer attached to the operation to document it in pictures. While he had a lot of images to show of captured Atlanta, Barnard had yet to take any of the March to the Sea. He had nearly recorded some scenes of the prison pen at Camp Lawton, but there hadn’t been sufficient time for him to set up the equipment or prepare the chemicals necessary for the job. Nonetheless, the sight of the graves and living pits used by some of the POWs left a powerful impression on the experienced war photographer. Barnard shared his thoughts on Camp Lawton with Major Hitchcock: “I used to be very much troubled about the burning of houses, etc., but after what I have seen I shall not be much troubled about it.”

Across the Ogeechee River from Sherman’s headquarters, offensive operations were under way, carried out by the Fifteenth Corps. In a series of actions that would foreshadow a future generation’s amphibious end runs, Major General Howard pushed forward a pair of fast-moving columns toward crossing points on the Ogeechee River, while a third was sent well south to undertake a similar mission at the Canoochee River.

One advance party, closely supported by a full brigade, headed for Wright’s Bridge, just below Guyton. “When we got there we found the bridge on fire and the rebels gone,” reported an Iowa soldier. “We built works on the bank of the river and went to repairing the bridge so we could cross. We sent six men across in a canoe. They got a shot at the rebs on the other side. As soon as we could cross on the bridge, Captain McSweeny took three companies and went out to the railroad, which was about four miles from the river, on a reconnaissance.” Continued a comrade: “While they were out the rebs came from [station] two and a half and attacked us at the bridge cutting off the three com

panies that were out.” However, the enemy promptly fell back, allowing the detached party to return later without incident.

The second fast-moving party targeted another Ogeechee crossing, this one at Jenks’ Bridge, near Eden. “Upon arriving at the river found the bridge destroyed,” reported the expedition’s commander, who made no crossing attempt. His men entrenched in an all-around defense, ready to take on any attacker from any direction. The smallest force, sent farthest south to the Canoochee River, determined that this crossing was destroyed and the opposite bank strongly held. The group retired “without doing the work.” Still, the Confederates in Savannah were on notice that Sherman’s army was drawing near.

Two of the Confederacy’s top military leaders were in Augusta this day. General Braxton Bragg spent his final hours in overall charge of stopping Sherman by coordinating several defensive moves along the vital Savannah-Charleston corridor, then under pressure from another Federal raiding force operating from the coast. At the same time he advised Joseph Wheeler to “press well on the enemy’s left flank, so that if he crosses [the] Savannah River you will know it immediately, and advise me.”

Bragg’s reluctant tenure came to an end this evening when General Beauregard rode into town to assume overall command. Now in touch with a working telegraphic connection to Richmond, Beauregard loaded it with a lengthy report, most of which justified his decision to allow John B. Hood to invade Tennessee instead of trying to engage Sherman. A small portion of the note addressed the growing crisis in eastern Georgia. Here Beauregard declared that “all that could be [done] has been done…to oppose the advance of Sherman’s forces toward the Atlantic coast. That we have not thus far been more successful none can regret more than myself, but he will doubtless be prevented from capturing Augusta, Charleston, and Savannah, and he may yet be made to experience serious loss before reaching the coast.”

In Washington today the protocols of a democracy were satisfied as the Congress informed the Executive Branch that a quorum was present,

allowing it to receive communications. President Abraham Lincoln promptly dispatched his annual State of the Union message. The lengthy document covered the course of foreign and domestic affairs, reviewed national finances, commented on agricultural conditions, and even welcomed Nevada as the nation’s newest state. Progress of the war was not ignored. “Since the last annual message all the important lines and positions then occupied by our forces have been maintained,” Lincoln announced, “and our arms have steadily advanced.”