Spies: The Rise and Fall of the KGB in America (80 page)

Read Spies: The Rise and Fall of the KGB in America Online

Authors: Harvey Klehr;John Earl Haynes;Alexander Vassiliev

The KGB cut contact with Cooke after learning he had cooperated

with the FBI. Seemingly not realizing that he had burned his bridges,

however, Cooke attempted to get in touch with Semenov at Amtorg in

May 1943. And in mid-1945 the KGB New York station reported: ""Octane" [Cooke] went into the "Factory" [Amtorg] building twice and asked

about Gennady [Ovakimyan]. He was told that they did not know of such

a person. Apparently, he had wanted to get a consulting position, b/c he

is currently unemployed." After that, Cooke dropped out of sight.02

The KGB also sought to use the American Communist Party's networks

for its technical intelligence operations. Anatoly Gorsky, the Washington

station chief, informed Moscow in 1945:

"In the process of working with "Vendor," the latter reported that for a number of years, he had been "Sound's" [Golos's] group leader and had handled a

group of people for us on his behalf. In particular, "Vendor'' indicated that his

next meeting with "Sound" was to have taken place on the day of the latter's

death." "Vendor's" contacts:

"i. Leon Josephson, 47 year-old lawyer, NY, owns a cafe, member of the

CPUSA. Assistant group leader, handled "Sound's" people. Went to Europe

several times, supposedly on our business. He failed in Copenhagen in '36

along with George Mink; he was convicted and extradited to the USA.

z. Hyman Colodny, 5o-5z years old, pharmacy in Washington, a fellowcountryman. "Sound" used him for a rendezvous apartment. In '34-'36, he was

in Shanghai on our business.

3. Rinis. A talent spotter.

4. Louis Tuchman, 55 years old, CP member, small-time building contractor.

Rinis's partner. A talent spotter. He was secretary for an illegal group of

Communists working in gov't agencies in Washington.

Marcel Scherer, 43-44 years old, CP member, an organizer for a trade

union of chemistry workers. A talent spotter.

6. Paul Scherer (Marcel's brother). 46-47 years old, CP member, a chemist, a

New York native, a trade union worker. 11 "30-'32 he and Marcel were

handled by Josephson. Their handler on our line was a certain "Harry" In

,35-36, Paul was connected with G. Mink, collecting tech. information and

obtaining books. Prior to "Sounds" death, both Scherer brothers were handled by Josephson."93

A strong candidate for "Vendor" is Harry Kagan, who worked for the

Soviet Government Purchasing Commission and whom Elizabeth Bentley identified as one of Jacob Golos's agents. The reference to Leon

Josephson having "failed in Copenhagen" (that is, been exposed to hostile security services) was to a 1935 incident in which Danish police

charged a traveling party of three Americans with espionage. The three

were George Mink (a former trade union organizer for the CPUSA then

working for the Comintern), Leon Josephson (a CPUSA lawyer), and

Nicholas Sherman. In Josephson's case, after four months in jail a Danish court decided there was insufficient evidence to proceed to a trial,

and he was released. Mink and Sherman, however, were convicted of espionage, spent eighteen months in prison, and were then deported to the

Soviet Union. Despite carrying an American passport, Sherman was not

an American. He was Alexander Petrovich Ulanovsky, a GRU officer.

Danish police found in his possession correspondence with Harry Kagan,

and among the four passports Mink had in his possession one was that of Harry Kagan. The American Communist Party ran a false passport operation (the "books" referred to in Gorsky's cable were passports), and GRU

was a major recipient of its work. Likely the four passports carried by

Mink were for delivery to GRU. (Kagan claimed his passport had been

stolen. The real Nicholas Sherman had died in 1926. The CPUSAs false

passport apparatus had used the dead man's naturalization papers along

with a false witness to allow Ulanovsky to obtain an American passport as

Nicholas Sherman. )94

"Rinis" was Joseph Rinis, a graduate of the Comintern's International

Lenin School and a CPUSA activist in the FAECT. Marcel Scherer, who

had been the founder of FAECT, was, like Rinis, described as "a talent

spotter"-that is, someone who identifies likely sources to be recruited

by Soviet intelligence. He had been born in Rumania in 1899 and was a

founding member of the American Communist movement. Known as

"the Bolshevik chemist" while a student at CCNY, he studied at the

Lenin School in 1930-31, before returning to be the leader of the

FAECT chapter in New York. He spent more time in the mid-1930s

working in the Anglo-American Secretariat of the Comintern. As the

president of FAECT, he was instrumental in its organizing efforts in the

late 193os and early 19405, personally overseeing the attempt to organize

a chapter at the Radiation Laboratory at Berkeley in 1942, the site of

much atomic bomb research. FAECT halted its campaign after President Roosevelt personally appealed to Philip Murray, chief of the CIO,

to end the effort on grounds of national security. Many of the scientists

and engineers implicated in Soviet espionage were FAECT members,

including Julius Rosenberg, Russell McNutt, and Joseph Weinberg.

With easy access to thousands of radically inclined scientific and technical personnel and knowledge of the projects on which they were working, Marcel Scherer was in an ideal position to assist Soviet intelligence

and steal American secrets, but there is no further mention of him or

his activities in the notebooks. He remained a steadfast member of the

CPUSA until his death.95

Scores of other technical sources, many identified with real names and

others with only cover names, appear in KGB reports. Some are described in detail, while most have only walk-on appearances. Some had

previously appeared in FBI investigations or congressional investigations,

but others, even when identified by their real names, are obscure and will require additional research to determine their contribution to Soviet

technical and scientific intelligence. What is clear is that the KGB invested a substantial amount of resources and personnel in its efforts to

steal American scientific, technological, and industrial secrets and harvested a rich return.

Support Personnel

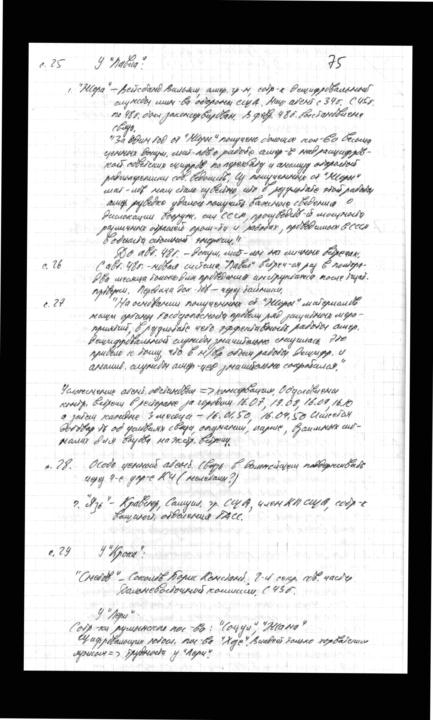

A 1950 KGB report on William Weisband, a one-time KGB courier who became a Soviet spy within the

super-secret National Security Agency and revealed to the USSR that the United States had broken its military codes. Courtesy of Alexander Vassiliev.

oviet espionage networks in the United States would not have

oviet espionage networks in the United States would not have

been able to function without the assistance of a number of dedicated support personnel whose role was as essential as that of

the sources who actually took documents from the government

offices in which they worked or communicated secrets to which they were

privy. Once the latter had obtained their information, they had to transmit it to the Soviets. Few of those who obtained government or technical secrets could easily meet with someone readily identified as a Soviet

national without exciting suspicion or triggering surveillance. In order to

avoid alerting American counterintelligence, a chain of clandestine contacts had to get the material from the original source and transmit it to either a "legal" KGB officer working in an official capacity in a consulate or

embassy with a cover job or an "illegal" officer living in the United States

under a false name and pretending to be an American or an immigrant.

Such illegals, once they obtained material from their sources, still had to covertly transmit it to a legal officer for final passage to the USSR by protected diplomatic pouch. These networks required couriers who could

meet the sources without arousing suspicion, pick up the material, and

then hand it on to the next person in the chain. Jacob Golos, for example,

used Elizabeth Bentley as his courier to the Silvermaster group because

he himself was in poor health and unable to travel frequently to Washington and because he believed himself under FBI surveillance. The

KGB needed a corps of such discreet, dedicated Americans willing to undertake unglamorous jobs that required regular travel and a low profile.

These courier chains, moreover, were sometimes intricate and complex. While this protected both the original source and the KGB officer

ultimately receiving the material by insulating them from each other, it

could cause delays in the Soviets' receipt of information, delays in the

passage of instructions from the Soviets to the source, and an inability to

control the source's behavior. For example, George Silverman, one of the

sources of the Silvermaster network, was civilian chief of analysis and

plans of the Army Air Force, a position of obvious interest for Soviet intelligence. But Moscow Center felt it wasn't receiving what it should from

him and in 1943 complained to its New York station: "`You communicate

with him through a highly elaborate system: "Aileron" [Silverman]-"Pal"

[Silvermaster] -"Clever Girl" [Bentley]-"Sound" [Golos]-"Vardo"

[Elizabeth Zarubin]. Clearly, with this kind of communication it is inconceivable to exert any kind of serious influence on a probationer's

[source's] work, not to mention his education.... Think over the question

of improving the line of communications with "Aileron" (primarily by, so

to speak, `shortening' it)."' Moscow had a point. Silverman, the original

source, was a hidden Communist, but he was an economist, not a trained

intelligence operative. He turned his material over to and got his guidance from Gregory Silvermaster, another economist with no more training in espionage than Silverman. He, in turn, handed the material over

to Elizabeth Bentley, Golos's assistant and lover. While she had experience in covert party work, Bentley was not an intelligence professional either. Such instruction as Bentley got was from Golos, a senior CPUSA

official whose techniques came from the Communist political underground, not the world of intelligence. It was not until the material

reached the fifth person in the chain, Elizabeth Zarubin, that it got to a

KGB professional. Moscow's complaint that Silverman lacked proper

guidance about what it needed or appropriate conspiratorial techniques

when there were three intermediaries was not misplaced.'

In some cases, American couriers also provided a psychological cover for the source. Since the person to whom he or she gave information was

not a Russian but an American, the source could pretend or rationalize

that he or she was not turning over material to a foreign power but to the

CPUSA. Bentley used that argument to resist turning members of the

Silvermaster network over to the direct supervision of the Soviets. On

the other hand, some sources thrilled to direct contact with Soviets. Silvermaster believed that Iskhak Akhmerov, an illegal officer with whom he

met frequently, was an American Communist; when he finally met with

Vladimir Pravdin, a legal officer operating under TASS cover, in September 1945, he gushed that he "`was sincerely pleased to meet with a

Soviet representative"' at last, saying "`that he had long hoped that they

would meet him, since all these years he had been connected `only to

local fellowcountiymen' [American Communists].' "2