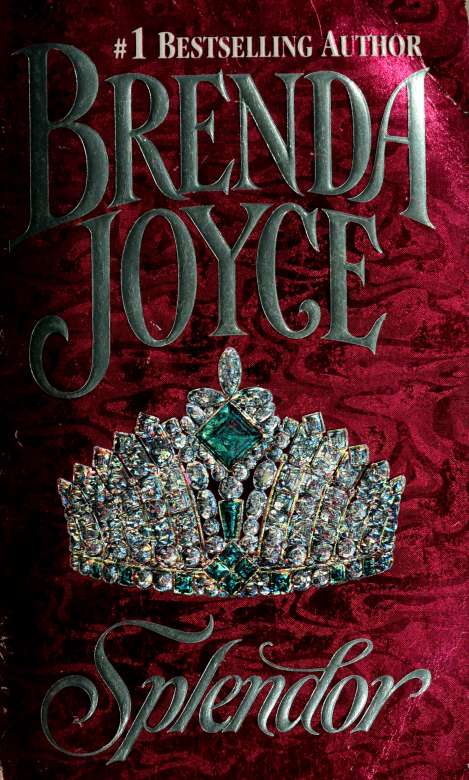

Splendor

This book made available by the Internet Archive.

This one is for Jen Enderlin, my editor. For being

brilliant, for being a joy to work with, and for

being a true believer—and a new friend.

Jen, thanks for everything.

^ Prologue ^

Knightsbridge, 1799

THEY were fighting.

Her mama and papa were fighting.

Tears slipped down her cheeks. Carolyn hugged her skinny knees to her chest, holding her breath, trembling and afraid. She could not understand what was happening. They never fought. But now they were shouting at one another and Carolyn could hear their every word from where she sat hunched over in her small bed. Their bedchamber was across the narrow hall; the bookshop her papa owned was downstairs. Carolyn's door was open because she didn't like the dark. But she almost wished that it were closed so she would not have to hear them.

Her father was shouting. Carolyn choked on a sob.

"Why won't you let me go?" Her mother was crying now. "How can it hurt to try?"

"You've written her two letters. And she did not even send a one-word reply!'' Her father cried.

Carolyn's mother, Margaret, wept.

"Oh, God," George said thickly. "Please, Mag, don't cry. I love you. I hate seeing you this way."

There was silence now.

Carolyn sucked down her sobs, rising impulsively to her feet. Her heart was banging against her chest. Clutching the folds of her cotton nightgown, she crept to the door. Her feet were bare and the wood floor was icy cold—outside.

it was snowing heavily, huge fat flakes sticking to the win-dowpanes. Surely if she went to her parents they would stop fighting and everything would be all right. Their door was ajar. Carolyn peeked around it.

Her father held her mother, who wept on his chest. He caressed her blond hair, tied into one long braid. Her parents were also dressed for bed. Carolyn felt better, seeing them in a familiar embrace, and she staited forward, to join them as she so often did, but her mother started to speak and instinct made Carolyn freeze.

Margaret lifted her head. "Let me try, George, before we lose everything. She is my mother," she pleaded.

He stiffened. "I'd rather lose everything than take her charity—and her abuse."

"If she only got to know you, she would love you—the way I do," Margaret cried, gazing at his face.

"She has hated me from the moment she found out about us, and that was six years ago. Face it, Mag. Your letters have gone unanswered. She doesn't want anything to do with you or our daughter—because of me."

"The government official was serious. They're going to auction this house and shop out from under us if we do not pay our debts. And then where will we go?" Margaret cried anxiously.

"I can find work in France. Or perhaps Stockholm or Copenhagen. And there is a huge foreign community in St. Petersburg. I will tutor nobly bom children again, the way I did when we first met." His smile was brief.

"France?" Margaret was horrified. "They are in the midst of a revolution! Stockholm? Russia?"

George stood. "What would you have me do if we lose our bookshop? Where would you have me go? Your mother has made it impossible for me to continue as a tutor in this country. She has not changed. There are no doors open for me here." Suddenly he sat beside her. "God, look at how I have ruined your life!"

"You have not ruined my life!" Margaret was fierce, and she hugged him, hard. "I love you. I always have, I

always will. I cannot imagine life without you, and I do not care how we live, only that we are together with our daughter, with a roof over our head and warm food in our belHes." She smiled, her eyes glistening.

He was grim. "We are going to have to move. Our landlord was not jesting. If we do not pay what we owe, they shall seize this house and all of our possessions."

Margaret stood abruptly. "You must let me go to my rnother. We are blood. In six years I have never asked her for anything. Let me ask her for her help now."

George did not move. And then he saw his daughter hovering in the doorway with wide eyes and tearstained cheeks. "Carolyn!" he cried. He stood and swiftly crossed the room, picking her up. She was five years old, but as light as a feather. He smiled. "Can't sleep?" He kissed her cheek.

Carolyn shook her head, not liking what she had heard. "Why is Mama crying? Why are you making her cry? Why won't you let her go where she wants to go?"

George turned white. "Darling, we are only having an argument. Sometimes people who love each other very much have different ideas and different opinions. It doesn't mean that we don't love each other. In fact, it is good for the mind and the soul. I love your mother more than I have ever loved anyone—other than you." He kissed her cheek again. But his tone was worried now.

Margaret had come over to them and she stroked her daughter's platinum hair. "Your papa is right. We are only discussing a trip I wish to make." She looked at George with sudden determination. "But your father is going to allow me to go to Midlands. And I will take you, Carolyn," she said firmly.

They had been traveling since early that morning, well before dawn. It had not stopped snowing. The entire Essex countryside was blanketed in white, the roads covered with huge drifts. Ponds and lakes were frozen over, and oaks and dogwoods bent double under the weight of their white

burden. Periodically the mail coach would halt and all the passengers were required to disembark, and one and all would have to push the vehicle free of the ruts, mud, and snow. Then, cold and aching, Carolyn and her mother would clamber back to their seats atop the coach and the vehicle would set off again.

Carolyn was hungry, tired, and cold, even though she wore many layers of clothing and a heavy wool coat. She and her mother were riding with two other passengers on the outside seats behind the coachman because they could not afford the seats inside the carriage. Although they had hot bricks wrapped in towels for their feet, it was frigidly cold and Carolyn wished their journey was over. Margaret could not stop shivering.

"We are almost there." Her mother had her arm around her, holding her tightly to her side as they shared their body heat. Margaret smiled at Carolyn, but her lips were oddly blue. "This is Owl Hill. When I was a child not too much older than you, I used to ride my pony here. There is a small lake on the other side. In the summer, I used to picnic there with my sister, Georgia. It was fun." Her expression had turned wistful.

"I like Aunt Georgia," Carolyn said truthfully. "Why haven't we seen her in such a long time?"

Margaret smiled and looked away, but the smile was forced and Carolyn saw the tears shimmering in her mother's eyes. "She is married and very busy these days." Her mother's tone was flat, and Carolyn knew the subject was closed.

The mail coach, pulled by four weary bays, halted. "We are here," Margaret said.

Carolyn squinted through the snow. The side of the road boasted a wooden fence and, beyond that, nothing but snow-covered meadows and snow-clad trees. "We are? Where is Midlands?"

"At the end of the drive. We shall have to walk, I am afraid." She smiled again, encouragingly.

Carolyn waited as the coachman helped her mother to

climb down to the ground, and then he lifted her down and set her on her feet beside Margaret. A big, lanky man bundled up in a wool overcoat and a huge scarf, he eyed Margaret kindly. "I do hope you ain't got too far to go, ma'am," he said.

"We are fine, but thank you for your concern." Margaret smiled at him and Carolyn saw her press a shilling into his hand. "That is for your kindness on this journey. I'm sorry it cannot be more."

He started. "I can't take this from you, ma'am!" He was blushing as he handed the coin back to her. ' 'Use it to feed the young one tonight."

Margaret smiled and took Carolyn's hand. They watched the coachman climb up to his seat, lift the reins, and drive the team forward. Snow blew in their faces as the mail coach hustled down the winter-white road. It grew smaller and smaller and smaller until it was a dark speck amidst the vast surrounding whiteness.

Carolyn saw the drive now, another snowy road that wound through the snow-covered fields on the other side of the fence. But she still could not see a house. "Mama?" she asked as they started walking, hand in hand. "I don't see your mother's house."

"It's about a mile from here," Margaret said. "But walking is better than sitting, don't you think? Shall we sing a song?" She was cheerful.

Carolyn did like walking better, because she was rapidly becoming less cold, although her mother's lips remained blue. "Mama, are you all right?"

"I am fine. Shall we sing 'Over the Hills and Far Away'?"

Carolyn griimed. Aild they started to sing.

Carolyn's eyes wfdened. Her grandmother's house was huge—and it seemed much more like a castle than a house. Long, relatively low and rectangular, it was built of huge slabs of pale taupe stone, with two towers forming wings on either side of the central building. In front of the en-

trance, which had a temple front and pediment, was a hme-stone water fountain. Low, sculpted hedges surrounded the fountain, now dry, and also bordered the house.

"Mama," Carolyn whispered, clutching her mother's hand. "She is rich."

"My mother is a viscountess, Carolyn." Her mother's teeth chattered as she spoke.

"But this is the kind of house the king hves in."

Margaret did manage to laugh. "It is impressive, but not that impressive, dear. It is just that you are not accustomed to the homes of society."

"But you grew up here?" Carolyn was amazed.

"We spent summers here—and Christmas."

Carolyn glanced up at her mother, whose tone had become husky. Her mother was very pale. She increased her grip on her mother's hand. Her mother seemed to be increasingly nervous—and even sad.

"Come," Margaret said. They walked past the limestone fountain, icy snow crunching under their shoes, and up the front walk, which was brick. It had been shoveled free of snow and salted. At the front door Margaret rang a bell, which resounded loudly. Behind them, the sky was already darkening. Soon night would fall.

A bald man in livery answered the door. He stared.

"Hello, Carter. Is my mother home?"

The footman blinked. His expression turned from sheer impassivity to utter surprise. "Lady Margaret?" he cried.

"Yes." Margaret smiled. "And my daughter, Carolyn." She held Carolyn's shoulder. Carolyn was incredulous— she had never heard her mother addressed as Lady Margaret before.

"Come in! Out of the cold!" He glanced past them, appearing perplexed when he did not see a coach in the drive.

"A mail coach dropped us off at the^foot of the drive," Margaret explained as they entered a large, spacious foyer with marble floors.

Carolyn gaped at her surroundings, standing as close to her mother as possible now, clinging to her hand. Ahead

of them was a sweeping staircase, the banister wrought iron, a red carpet runner on the steps. How could her mama have Uved here? It was as if her mama had been a princess! "You walked! In this weather?" Carter was stunned. Another servant, in black, entered the foyer. Now Margaret was really smiling. "Hello, Winslow." "Lady Margaret!" The butler rushed forward, as if to embrace her, but then he skidded to a halt and dropped his arms to his sides. "How good to see you, my lady, how awfully good."

Margaret kissed his cheek. "It is awfully good to see you, too, Winslow. This is my daughter, Carolyn." Margaret pulled Carolyn forward.

Winslow beamed. "She is just like you, my lady, if you do not mind my saying so," the butler said.

"Winslow, Lady Margaret and her daughter walked all the way from the road," Carter said disapprovingly.

Winslow straightened. He was appalled. "Let me take your coats. I will bring hot tea immediately."

Margaret no longer smiled. "I think, before you bring any refreshments, that you should tell my mother that I am here," Margaret said.

Winslow stared. His expression was impossible to read.

"She is in residence, is she not?"

"Yes, Her Ladyship is at home." The butler's gaze

shifted. "Very well," he said. He bowed. "I will be right

back." He mmed and strode briskly down the corridor, past

the sweeping staircase, and disappeared.

Margaret reached for and took Carolyn's hand. Carolyn looked up and saw the worry on her face. "Don't worry. Mama," she said in a whisper. "Everything will be all right" But she was still in disbelief. How could her mother have grown up here, in this castlelike place? And was she really Lady Margaret and not Mrs. Browne?

Margaret bent and kissed her daughter. "I love you," she whispered.

"I love you too. Mama," Carolyn said.

Margaret straightened just as rapid, no-nonsense foot-

steps could be heard approaching. She paled.

A slim, gray-haired woman with a handsome face and a set expression marched into view, her pale green gown swirling about her. She saw them and halted in her tracks. Mother and daughter stared at one another. Carolyn looked from one to the other and felt dread. The old lady was angry. Her eyes were cold. And her mother was clearly afraid.

"Hello, Mother," Margaret whispered almost inaudibly.

The viscountess came forward. "What are you doing here?" she demanded. Her gaze moved to Carolyn, swept over her, making Carolyn feel as if something were terribly wrong with her, and then it returned to Margaret. "Did you not tell me that you would never come back?"

Margaret swallowed. "That was six years ago."

"Oh? So you have changed your mind? Are you leaving him?"

Margaret's face was pinched. "My feelings have not changed. But I pray that yours have. Did you get my letters?" she asked.

"Yes." One word, harsh, uncompromising, final. Lady Stafford stared. The viscountess glanced at Carolyn, but it was impossible to decipher what she was thinking. "Did you think to soften me by bringing her here?"

"Yes, frankly, I did," Margaret said, her voice choked with tears.

"Well, such a ploy will not work," Edith Owsley stated. "You made your choice, Margaret, all those years ago. Now, if you will excuse me?"