Strolling Through Istanbul: The Classic Guide to the City (8 page)

Read Strolling Through Istanbul: The Classic Guide to the City Online

Authors: Hilary Sumner-Boyd,John Freely

Tags: #Travel, #Maps & Road Atlases, #Middle East, #General, #Reference

TOWARDS HAGH

İ

A SOPH

İ

A

Just beyond Zeynep Sultan Camii and on the same side of the avenue we see a short stretch of crenellated wall, almost hidden behind an auto-repair shop; this is all that remains of the apse of the once-famous church of St. Mary Chalcoprateia. This church, which is thought to date from the middle of the fifth century, was one of the most venerated in the city, since it possessed as a relic the girdle of the Blessed Virgin. After the Nika Revolt in the year 532, when the church of Haghia Sophia was destroyed, St. Mary’s served for a time as the patriarchal cathedral. It was built on the ruins of an ancient synagogue which since the time of Constantine had been the property of the Jewish copperworkers, hence the name Chalcoprateia, or the Copper Market.

The handsome though forbidding building that occupies most of the opposite side of the avenue here is the So

ğ

uk Kuyu Medresesi. This theological school was founded in the year 1559 by Cafer A

ğ

a, Chief White Eunuch in the reign of Süleyman the Magnificent, and was built by the great Sinan. The hillside slopes quite sharply here, so Sinan first erected a vaulted substructure to support the medrese and its courtyard. The entrance to the medrese is approached from the street running parallel to the west end of Haghia Sophia, where an alleyway leads down to the inner courtyard of the building. The student cells of the medrese are arrayed around the courtyard, with the dershane, or lecture hall, in the large domed chamber to the left as you enter. The medrese now serves as a bazaar of old Ottoman arts and crafts, as well as a restaurant serving traditional Turkish food in a picturesque setting.

Alemdar Caddesi now brings us out into the large square which occupies the summit of the First Hill. On our left we see the great edifice of Haghia Sophia, flanked by a wide esplanade shaded with chestnut and plane-trees. Straight ahead is Sultan Ahmet I Camii, the famous Blue Mosque, its cascade of domes framed by six slender minarets. In front of the Blue Mosque is the At Meydan

ı

, the site of the ancient Hippodrome, three of whose surviving monuments stand in line in the centre of a park. This is the centre of the ancient city, and the starting-point for our next five strolls through Stamboul.

“The church presents a most glorious spectacle, extraordinary to those who behold it and altogether incredible to those who are told of it. In height it rises to the very heavens and overtops the neighbouring houses like a ship anchored among them, appearing above the city which it adorns and forms a part of … It is distinguished by indescribable beauty, excelling both in size and the harmonies of its measures.” So wrote the chronicler Procopius more than 14 centuries ago, describing Haghia Sophia as it appeared during the reign of its founder Justinian I. Haghia Sophia, the Church of the Divine Wisdom, was dedicated by Justinian on 26 December 537. For more than nine centuries thereafter Haghia Sophia served as the cathedral of Constantinople and was the centre of the religious life of the Byzantine Empire. For 470 years after the Turkish Conquest it was one of the imperial mosques of Istanbul, known as Aya Sofya Camii. It continued to serve as a mosque during the early years of the Turkish Republic, until it was finally converted into a museum in 1935. Now, emptied of the congregations which once worshipped there, Christians and Muslims in turn, it may seem just a cold and barren shell, devoid of life and spirit. But for those who are aware of its long and illustrious history and are familiar with its architectural principles, Haghia Sophia remains one of the truly great buildings in the world. And it still adorns the skyline of the city as it did when Procopius wrote of it 14 centuries ago.

The present edifice of Haghia Sophia is the third of that name to stand upon this site. The first church of Haghia Sophia was dedicated on 15 February in the year A.D. 360, during the reign of Constantius, son and successor of Constantine the Great. This church was destroyed by fire on 20 June 404, during a riot by mobs protesting the exile of the Patriarch John Chrysostom by the Empress Eudoxia, wife of the Emperor Arcadius. Reconstruction of the church did not begin until the reign of Theodosius II, who succeeded his father Arcadius in the year 408. The second church of Haghia Sophia was completed in 415 and was dedicated by Theodosius on 10 October of that year. The church of Theodosius eventually suffered the same fate as its predecessor, for it was burned down during the Nika Revolt on 15 January 532.

The chronicler Procopius, commenting on the destruction of Haghia Sophia in the Nika Revolt, observed that “God allowed the mob to commit this sacrilege, knowing how great the beauty of this church would be when restored.” Procopius tells us that Justinian immediately set out to rebuild the church on an even grander scale than before. According to Procopius: “The Emperor built regardless of expense, gathering together skilled work men from every land.” Justinian appointed as head architect Anthemius of Tralles, one of the most distinguished mathematicians and physicists of the age, and as his assistant named Isidorus of Miletus, the greatest geometer of late antiquity. Isidorus had been the director of the ancient and illustrious Academy in At hens before it was closed by Justinian in the year 529. Isidorus, who was placed in charge of the building of Haghia Sophia after the death of Anthemius in the year 532, is thus a link between the worlds of ancient Greece and medieval Byzantium. Just as the Academy of Plato had been one of the outstanding institutions of classical Greek culture, so would the resurrected Haghia Sophia be the symbol of a triumphant Christianity, Byzantine-style.

The new church of Haghia Sophia was finally completed late in 537 and was formally dedicated by Justinian on 26 December of that year, St. Stephen’s Day. Hardly had the church come of age, however, when earthquakes caused the collapse of the eastern arch and semidome and the eastern part of the great dome, crushing beneath the debris the altar with its ciborium and the ambo. Undaunted, Justinian set out to rebuild his church, entrusting the restoration to Isidorus the Younger, a nephew of Isidorus of Miletus. The principal change made by Isidorus was to make the dome somewhat higher than before, thereby lessening its outward thrust. Isidorus’ solution for the dome has on the whole been a great success for it has survived, in spite of two later parti al collapses, until our own day. Restorations after those collapses, in the years 989 and 1346, have left certain irregularities in the dome; nevertheless it is essentially the same in design and substantially also in structure as that of Isidorus the Younger.

The doors of Haghia Sophia were opened once again at sunrise on Christmas Eve in the year 563, and Justinian, now an old man in the very last months of his life, led the congregation in procession to the church. Here is a poetic description of that occasion by Paul the Silentiary, one of Justinian’s court officials: “At last the holy morn had come, and the great door of the newly-built temple groaned on its opening hinges, inviting Emperor and people to enter; and when the interior was seen sorrow fled from the hearts of all, as the sun lit the glories of the temple. ‘Twas for the Emperor to lead the way for his people, and on the morrow to celebrate the birth of Christ. And when the first glow of light, rosy-armed, leapt from arch to arch, driving away the dark shadows, then all the princes and people with one voice hymned their songs of praise and prayer; and as they came to the sacred courts it seemed as if the mighty arches were set in heaven.”

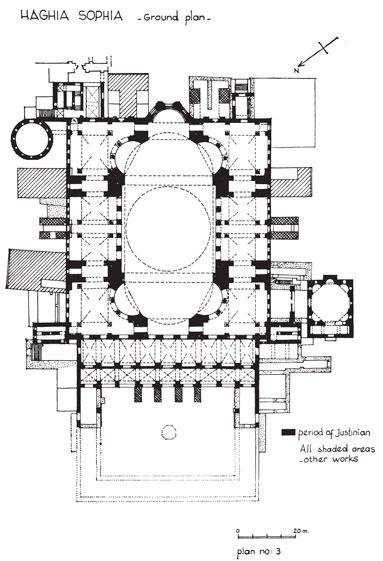

Although Haghia Sophia has been restored several times during the Byzantine and Ottoman periods, the present edifice is essentially that of Justinian’s reign. The only major structural additions are the huge and unsightly buttresses which support the building to north and south. Originally erected by the Emperor Andronicus II Palaeologus in 1317, when the church seemed in imminent danger of collapse, they were restored and strengthened in Ottoman times. The four minarets at the corners of the building were placed there at various times after the Conquest: the south-east minaret by Sultan Mehmet II, the one to the north-east by Beyazit II, and the two at the western corners by Murat III, the work of the great Sinan. The last extensive restorations were commissioned by Sultan Abdül Mecit and carried out by the Swiss architects, the brothers Fossati, in the years 1847–9. As a result of this and later minor restorations and repairs, Haghia Sophia is today structurally sound, despite its great age, and looks much as it did in Justinian’s time.

THE CHURCH

The original entrance to Haghia Sophia was at its western end, where the church was fronted by a great atrium, or arcaded courtyard, now vanished. The present entrance to the precincts of Haghia Sophia brings one in through the southern side of this atrium, now a garden-courtyard filled with architectural fragments from archaeological excavations in Istanbul. From the eastern side of this atrium five doorways gave entrance to the exonarthex, or outer vestibule, and from there five more doorways led to the inner vestibule, the narthex. The central and largest door from the atrium to the exonarthex was known as the Orea Porta, or the Beautiful Gate, and was reserved for the use of the Emperor and his party. (Just to the left of this portal one can see the excavated entryway to the so-called Theodosian church, the predecessor of the present edifice, which is described in the section on the Precincts of Haghia Sophia.) In addition to the Orea Porta, the Emperor also used an entryway which led into the southern end of the narthex, where the present public exit from the edifice is located, passing through a long and narrow passageway which in Byzantium was called the Vestibule of the Warriors. Here according to the

Book of Ceremonies

, the manual of Byzantine court-ritual, the Emperor removed his sword and crown before entering the narthex, and here the troops of his bodyguard waited until his return.

While passing through the vestibule we should notice the gold mosaics glittering on the dark vault; these are part of the original mosaic decoration from Justinian’s church. The great dome, the semidomes, the north and south tympana and the vaults of narthex, aisles and gallery – a total area of more than four acres – were covered with gold mosaics, which, according to the Silentiary, resembled the midday sun in spring gilding the mountain heights. It is clear from his description and that of Procopius that in Justinian’s time there were no figural mosaics in the church. A great deal of the Justinianic mosaic still survives – in the vaults of the narthex and the side aisles, as well as in the 13 ribs of the dome of Isidorus which have never fallen. It consists of large areas of plain gold ground, adorned round the edges of architectural forms with bands of geometrical or floral designs in various colours. Simple crosses in outline on the crowns of vaults and the soffits of arches are constantly repeated, and the Silentiary tells us that there was a cross of this kind on the crown of the great dome. This exceedingly simple but brilliant and flashing decoration must have been very effective indeed.

Whatever figural mosaics may have been introduced into the church after Justinian’s time were certainly destroyed during the iconoclastic period, which lasted from 729 till 843. The figural mosaics which we see in Haghia Sophia today are thus from after that period, although there is far from being unanimous agreement among the experts as to the exact dates. Most of them would appear to belong to the second half of the ninth century and the course of the tenth century, although some are considerably later.

In the lunette above the doorway at the inner end of the Vestibule of the Warriors, we see one of the two mosaic panels which were rediscovered in 1933, after having been obscured for centuries by whitewash and plaster. Since that time other mosaics in the nave and gallery have been uncovered and restored, and their brilliant tesserae now brighten again the walls of Haghia Sophia, reminding us of the splendour with which it was once decorated throughout. The mosaic in the Vestibule of the Warriors is thought to date from the last quarter of the tenth century, from the reign of Basil II, the Bulgar-Slayer. It depicts the enthroned Mother of God holding in her lap the Christ-Child, as she receives two emperors in audience. On her right “Constantine the Great Emperor among the Saints” offers her a model of the city of Constantinople; while “Justinian the illustrious Emperor” on her left presents her with a model of Haghia Sophia: neither model remotely resembles its original!