Summit (51 page)

Authors: Richard Bowker

"Going to try and keep out the world?"

"I have to, Charles."

"Won't be easy."

"No, but I figure a lot of money will help."

"You're probably right."

* * *

They were walking past the swimming pool beneath a hot Florida sun. "Your father saved my life, Danny. I can't thank him now, so I wanted to thank you!"

"You're welcome, I guess." Danny thought for a moment. "They gave him a medal, you know. It was post—post—"

"Posthumous. He deserved it." He noticed Danny's mother watching them from the door of her apartment. She didn't trust him; he meant trouble. He supposed she was right.

"I've got all that stuff now," Danny said. "He even sent me this special hockey puck from when he won a big tournament in college!"

"He told me you're quite a hockey player!"

Danny smiled; he was missing a tooth. "Not as good as him, though."

* * *

He stared down at the old woman with the tubes coming out of her. "I'm sorry," he said. Her eyelids fluttered. Did that mean she understood? "I'm sorry," he repeated. But words weren't enough. Perhaps it was too late for words. And that left only one thing—perhaps the only thing they had in common, besides the fierce love that neither of them knew how to express. He put a cassette in the tape player by her bed and started it. The sounds of the Tristesse etude filled the hospital room. "This is all I know how to say," he whispered, "and you helped me say it."

He sat beside her then and held her hand while they listened to the music.

* * *

"Time to go to bed, I think," Valentina said.

Fulton opened his eyes. The fire was low. He arose, and they went upstairs together, holding hands.

They stopped first in the nursery. Fulton walked over to the crib and looked down at his sleeping son. He fussed needlessly with the blanket. His son ignored him and went about his business. As always, the reality of this living person managed to startle and, in a way, frighten Fulton, but he was getting used to it. "How are things, Billy?" he murmured. "Still have your father's psychic ability and your mother's musical talent? I certainly hope so."

Billy didn't respond.

Fulton turned to look out the window. Valentina stood next to him. The snow fell softly on the fir trees and the birches and, in the distance, on the fence and the guards patrolling it. The scene was beautiful and terrifying, like all of life. "There is no real protection, is there?" he said to his wife. "Billy will have to go beyond that fence someday, and so will you."

"It's true," Valentina replied. "But at least we are free to do so—free to take the risk."

"That's worth something, I suppose."

"It's worth everything, Daniel."

She was right, he knew. Fulton leaned into the crib and kissed his son. "Sweet dreams," he whispered. And then, while the snow fell and the guards patrolled, he and Valentina went off to bed themselves.

They slept well, and they did not dream at all.

The End

Want more from Richard Bowker?

Page forward for excerpts from

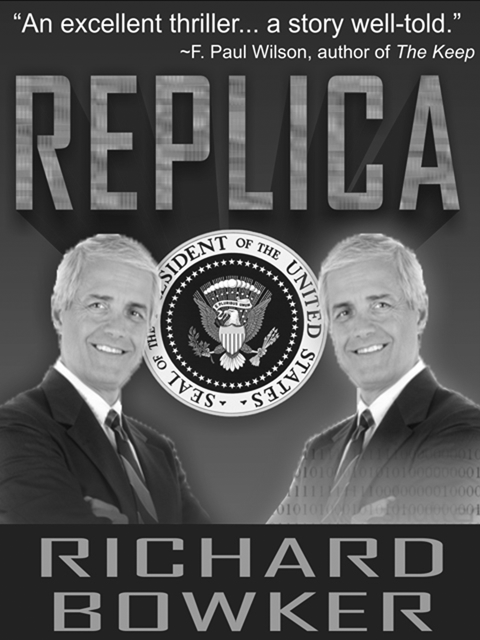

REPLICA

A Techno-thriller

SENATOR

A Thriller/Suspense Novel

PONTIFF

A novel of religion, murder, and miracles

Excerpt from

Replica

A Techno-thriller

by

Richard Bowker

Praise for Richard Bowker's

REPLICA

"While maintaining a highly readable pulp-fiction style, Bowker takes the narrative through a gripping array of turnabouts, doublecrosses and twists. Readers will be guessing the story's outcome until the very end."

~Publisher's Weekly

"Like any good writer of thrillers, Bowker has filled his plot with so many twists and turns that you'll never guess how the story turns out."

~

Chicago Tribune

"

Replica

is quite a book. It has everything I like in a novel: characters I cared about, a well-realized future setting, a fluid style that carried me effortlessly from page to page, and a suspenseful plot that kept me up well into the wee hours of the morning."

~

F. Paul Wilson

, author of

The Keep

"Bowker's novel succeeds both as a science fiction and as a contemporary thriller."

~

San Francisco Chronicle

It was the last day of his life, and the man in the blue nylon jacket was getting nervous.

He stood on the common, hands stuffed in his pockets. It was a little after two by the town-hall clock. He would be dead by a quarter to three.

The crowd was growing now. Lots of Norman Rockwell families: pink-cheeked grandmas, kids in snowsuits clutching balloons, strong-boned women pushing strollers. Plenty of bored, burly policemen. And the occasional gimlet-eyed man in a gray overcoat, watching.

The high school band was playing next to the temporary stage; a young woman was testing the sound system; the hot-chocolate vendors were doing terrific business. What better way to spend a Sunday afternoon?

He hadn't expected to be nervous. But everything was real now, and nothing can prepare you for the reality of death.

He had parked his car in a supermarket lot at the edge of town. It occurred to him that he could turn around, walk back to it, and drive away. Life would go on.

This struck him with the force of great insight. He had been anticipating this day for so long now that the idea of living it like any other day was strange and compelling.

Which would be harder: dying, or living with the knowledge that he had failed?

A helicopter swooped by, and then returned to hover overhead. The band played "From the Halls of Montezuma."

He remembered sitting in the bleak apartment and listening to the others spin their crazy schemes. They were dreamers; worse than dreamers, because they thought they were doing something wonderful and dangerous, when all they were really doing was wasting their lives. "You're trying to get something for nothing," he told them, "and you're not clever enough for that. If you want to do this, then you've got to be willing to risk everything—and then it becomes easy."

But they weren't willing. And he was. So he had left them behind, to end up here and take the risk.

He had been on the road for days. The distance to be traveled was hardly great, but he felt a need to disappear, to find some anonymity in the grimy motels and the self-service gas stations and the fast-food restaurants. Family, lovers, friends, work—it would be easier, he had thought, if he left them all far behind.

But here he was, and it was hard.

Distant sirens. Little boys had climbed the bare trees; infants were perched on parents' shoulders, necks craned, placards waved. Flashing lights, the roar of motorcycle engines, the cheering of the crowd...

...and there he was! Yes, look, in person—something to tell your grandchildren. Reach out and maybe he'll touch your hand!