Surrounded by Enemies (21 page)

Read Surrounded by Enemies Online

Authors: Bryce Zabel

The Twenty-Fifth Amendment did not exist yet. This created one of the most complex political equations ever seen in American history. One of the largest variables was Lyndon Johnson.

While the Kennedys’ first choice was for JFK to remain in office, their back-up position was to be able to pick his successor. Yet as things stood, if President Kennedy were to be impeached, that would mean Johnson would become the next President, an option completely unacceptable to John and Bobby Kennedy, who loathed him.

Johnson’s legal troubles made him vulnerable as well, but even if he could be quickly forced to resign, President Kennedy could not appoint anyone to take his place. Based on the Constitution as of 1965, if the Vice President’s office were to be left vacant for any reason, the position could not be filled until the next general election. Only when the Twenty-Fifth Amendment was ratified in 1969 were the terms of presidential succession finally clarified, allowing the President to appoint a new Vice President, subject to congressional approval.

This meant that if Johnson resigned and Kennedy were impeached, the next in line to assume the presidency would be the Speaker of the House. With the Republicans in control of the House of Representatives, that would mean that the genial but conservative Gerald Ford would get to serve out Kennedy’s term.

The Republican hold on the House of Representatives meant, oddly enough, that the more a Democrat felt a Kennedy impeachment was possible, the more likely that he would want to keep Vice President Johnson in office, corrupt or not. Otherwise, Congress could hand the presidency to Ford and the Republicans. For this reason, the GOP had joined the drumbeat in Washington, D.C., predicting Johnson’s imminent political demise. They needed him out of office before they trained their fire on Kennedy.

It is a testament to just how much the Kennedy White House sought to block the ascension of Lyndon Johnson that they became fierce and uncompromising in the battle to force him out. Bobby had never liked anything about the man, but now he felt there was more to it. He actually began to believe that LBJ had foreknowledge of the Dallas assassination attempt. He and his brother were determined to prevent any possibility of Johnson becoming President, even if it meant handing the country’s leadership to the Republicans. This created an unholy alliance of shared interest, never formal or even discussed, between JFK and the leaders of the Republican party to oust LBJ.

Robert Kennedy called a meeting of his young Turks and gave them a new mission. Behind closed doors and zipped lips, RFK announced that LBJ must be forced out, the sooner the better. He needed to know everything that was knowable about Lyndon Johnson, particularly anything that might have implicated him in any prior knowledge of the attack in Dallas.

Even though Lyndon Johnson had to go and go soon, all the President’s men knew the corollary political reality that followed with it. John Kennedy, however flawed and damaged he might be, had to stay in office. They did not intend to hand over the nation's stewardship, either to Johnson or to a Republican President Ford, without a fight.

The revelations about John Kennedy shot through the Joint Committee on the Attempted Assassination of the President like a surge of electricity. Having already subpoenaed Chicago mob boss Sam Giancana, the way was now open to also force the girlfriend he had shared with Kennedy to testify. The ostensible reason that Judith Campbell was sworn in to testify was to see if she had been told anything by Giancana that would implicate him in ordering the Dallas hit. Once she was under oath, however, asking her about her relationship with JFK was simply too tempting. She spent two entire days being grilled. The most damning information she delivered was her confirmation that Giancana felt he had been “double-crossed” by the Kennedys and had been overheard speaking to his lieutenants about how he wished JFK were dead.

America was at a boiling point. While the hearings were winding down, the Watts Riots in Los Angeles from August 11-17 provided a violent backdrop, leaving thirty-four dead, more than one thousand injured and close to four thousand arrested, and also caused more than $40 million in property damage.

As the long, hot summer claimed its victims on the West Coast, JCAAP continued its work on Capitol Hill. On August 19, two days after what rioters called “the rebellion” in Los Angeles had ended under the thumb of the National Guard, the committee issued its report on Dallas.

The Joint Committee on the Attempted Assassination of the President finds that the rifle attack on the motorcade of President Kennedy in Dallas, Texas on November 22, 1963 was probably the result of a conspiracy. The Committee believes on the basis of all available evidence that Lee Harvey Oswald did, in fact, participate in the assassination attempt. The Committee also believes that Oswald was not the sole assassin and that evidence supports the existence of a second and, possibly, a third gunman.

Beyond that, the Committee was vague. It did not name names and expose whom it actually thought was a part of that conspiracy. In fact, it ruled out several possibilities, saying that it did not believe “on the basis of all available evidence” that the Soviet Union or the Cuban government was behind what had happened. Ample evidence had been found, however, to implicate “rogue elements” of the CIA, the Cuban exile community, and organized crime. It did not find sufficient reason to say that any single group had organized it, only that the conspiracy had probably drawn resources and manpower from a “linkage or connection” of these groups. In this way, it held the institutions responsible for not policing their own employees but not necessarily for planning the attack.

Of particular importance in the report’s conjecture was the “probability” that the assassination plot that had placed John Kennedy in its crosshairs had its origin in an assassination plot that had been intended for Fidel Castro. Under this scenario, the plot was redirected at Kennedy based on pent-up frustration with the President. The clear implication was that anti-Castro Cubans were integral to the well-planned attack on the Kennedy motorcade.

On August 23, 1965, the first Monday after the Joint Committee on the Attempted Assassination of the President made its report public, the Republican Speaker of the House, Gerald Ford, held a news conference to announce that the Committee on the Judiciary in the House of Representatives would begin to consider impeachment charges against President Kennedy. Most Democrats made a show of halfheartedly accusing their Republican counterparts of playing politics and reminded them that impeachment was not inevitable as the GOP held control of the House by only a single vote.

National Review

editor William F. Buckley wrote a column in which he stated his opinion on the subject: “I should think a single vote would do the trick.”

The next day President John Kennedy gathered with his inner circle in the Oval Office to discuss strategy. “Maybe I have to go, but if I do,” he warned everyone, “those treasonous bastards are going with me.”

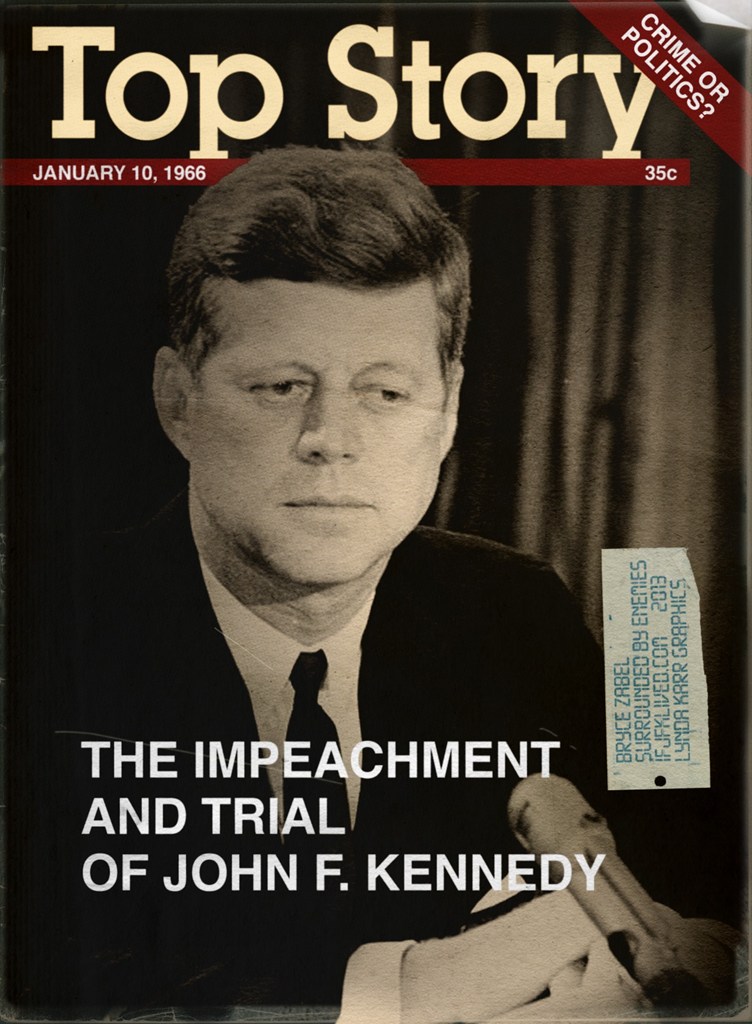

Impeachment and Trial

_______________

T

hinking about how our world would have been so different had President Kennedy's brilliant flame been extinguished on that bright and clear Dallas afternoon is a “what-if” that our scholars have been playing out for decades. They wonder if a President Lyndon Johnson would have pursued a war in Vietnam, what the success of the conspirators would have meant to America’s sense of itself, and whether Kennedy would have become a martyr in his death.

In the real world, however, even historians now consider the struggle between the Kennedys and their enemies to be the most shattering constitutional crisis our government has faced since the Civil War. The President fought back with everything he had. His adversaries spared nothing in return. In the end, the epic battle waged in the mid-1960s made it seem that JFK’s political survival was not the point anyway.

On an unusually muggy August day, Gerald Ford stood before reporters, sweating heavily in a jacket he refused to take off, and said that as Speaker of the House, he would not take a position on whether President Kennedy should remain in office unless the House Committee on the Judiciary agreed on the articles of impeachment. He would simply see to it that the process ran as smoothly as possible until it had run its course. As he put it, “America’s long, national nightmare since Dallas must come to an end one way or another.” Ford, a strict constructionist of the U.S. Constitution, told Kennedy in a private phone conversation that he could see no other way than impeachment. No matter what the outcome, it would either legitimize the President’s second term or end it altogether.

As events unfolded during the march toward impeachment, even John Kennedy’s popularity could not hold off the blowback from his years of incautious behavior. The cascading revelations felt like a betrayal to most voters. Like Jackie Kennedy responding to her own marriage, the relationship with voters now felt like a sham. The question to be decided was whether or not the relationship could be saved.

Few would have enjoyed the resulting spectacle even if it had been unleashed in a vacuum where no attempt had been made on Kennedy’s life. As experienced in the shadow of that violence, everything seemed dirty and lethal at the same time. The curtain had been pulled back on anti-democratic plotters that would assassinate an American President as a matter of convenience, power or greed. Now it seemed as if the President might have unleashed some of these destructive forces on himself.

One result of Kennedy’s reckless behavior and all the arguments about it was confusion. Suddenly the ground under the debate about the attack on the President shifted to Kennedy himself. Shadowy conspiracies were difficult to understand and nearly impossible to prove. Affairs, sex scandals and drug-taking could be talked about by the common man and woman, and talk they did. The leaks of the FBI files accomplished exactly what the leakers had hoped. The subject was changed. It made no difference that it was a crime to gather some of this information or to leak it. Overnight, it seemed, there were so many potential crimes to discuss that the average person could hardly be blamed for throwing up his hands in frustration at the mess of it all.

John Kennedy is not the only president who has ever faced an impeachment by the House of Representatives and a trial in the United States Senate, but his story is surely the most tragic. Indeed, since the Kennedy case, impeachment has been threatened or acted upon with sufficient regularity (Richard Nixon, Bill Clinton, George W. Bush) that it seems more like a parliamentary vote of no confidence than the last-ditch constitutional remedy the Founding Fathers intended it to be. Each party, the Democrats and the Republicans, has embraced the process in what many now view as a partisan tit-for-tat.

In late 1965, however, it had been nearly a full century since the impeachment of any President of the United States had been seriously contemplated. Ironically, the story of how Lincoln’s successor, Andrew Johnson, had been kept in office by a single vote in his Senate trial was one of the stories that John Kennedy had written about in his Pulitzer-winning book,

Profiles in Courage

. Not a single person with a conscious memory of that earlier event, however, was even alive in the mid-1960s. Everything in the process felt like the first time.

Historians now seem to agree that the implosion of John Kennedy’s reputation shocked most Americans even more than the failure in Vietnam. Yet revisionist thinking also has it that seeing his power slipping away through the fall and winter of 1965-66, Kennedy stiffened his resolve to prevent the United States from becoming fully involved in a land war in Asia while he still had the chance.

Even as Kennedy’s efforts to save himself politically dissolved, so, too, did any chance to prop up the South Vietnamese government. He knew that his choices had narrowed. Having straddled the middle ground longer than he ever thought he would, JFK now realized he could either turn up the heat with a vast new commitment of American military power, or he could wind it down and let it end. There seemed to be no responsible choice in between.

So, even as the House, and then the Senate, debated what to do about the Kennedy presidency, the still-incumbent commander-in-chief decided the war in Vietnam must end. In a series of three executive orders, President Kennedy declared a halt to all aerial bombing of North Vietnam, forbade American military advisers from operating in active combat roles, and organized the U.S. forces in established military bases where they would plan their eventual return in six months’ time.

The Kennedy administration then asked the North Vietnamese for peace talks through diplomatic channels. The talks began, but the North’s military campaign continued. Kennedy’s withdrawal literally showed that the South Vietnamese forces had no real will to fight. It became only a matter of time, a deathwatch. The reorganization on the ground did not go smoothly. It was no secret that the Joint Chiefs felt this was a suicidal retreat and were slow to implement. One unnamed, high-ranking U.S. commander said, “We were hoping to run out the clock on him. Stall long enough for the bastard to get his ass thrown out of office, then cut a better deal with the next guy.”

Back in the United States, the public was deeply divided. A plurality actually favored withdrawal of forces, but favoring it in the abstract and watching it happen on the nightly news was something else. And the people who were opposed saw this as another example of why Kennedy had to go. In their view, he was simply too weak and too naïve to continue to serve as President of the United States.

By refusing to deepen American involvement in the war under his own authority as commander-in-chief, President Kennedy had practically dared Congress to demand that troops be sent. As it turned out, the majority of representatives and senators favored war only if the President would take the ultimate responsibility. Without the cover of his leadership, the hawks in Congress fell surprisingly silent. The unexpected gift of Kennedy's troubles may very well have been the saving of hundreds of thousands of lives in Southeast Asia.

In the end, the Vietnam situation did not gain the President any support, and it probably cost him some. He took the actions he did for practical reasons. He opposed widening the war, and he knew he could end it if he moved quickly. His presidential power was waning.

In February 1966, the South Vietnamese government fell to forces loyal to North Vietnam’s Ho Chi Minh. The American withdrawal was underway simultaneously. The TV newscasts juxtaposed images of Viet Cong raising their flag over the old American embassy, against film showing U.S. soldiers cutting and running with their tanks and planes and helicopters. It was ruinous theater of the national mood, raising anger, and it was in the news along with the latest events from the Kennedy impeachment story.

Under the leadership of Speaker Ford, the House Committee on the Judiciary was encouraged to get the job done on the issue of impeachment before adjournment. That was originally scheduled for late October, but Ford said he would keep the House working until Christmas Eve, if necessary. Ford’s firewall was his determination that the fate of John F. Kennedy would be out of his House by 1966.

Impeachment, then, began with a ticking clock of approximately four months. That amount of time was considered short by virtually everyone but Ford, who remained adamant that JFK’s fate not derail the upcoming second session of the Eighty-Ninth Congress.

The Speaker further argued that the President’s fate was not a topic that should need great investigation, given the publicity to date, a statement that even members of his own party felt was simplistic and wrong. Yet it was Ford’s decision to make, and he had made it. Do whatever you feel is right, he seemed to be saying to the Congress, but do it fast.

Most constitutional scholars consider the House Committee on the Judiciary, backed up by the full body of the House of Representatives, to be the equivalent of a grand jury. The lower body of the U.S. government is empowered to conduct official proceedings to investigate potential criminal conduct (i.e., treason, bribery and other high crimes and misdemeanors) and to determine whether criminal charges should be brought before the upper body (i.e., sent to the U.S. Senate for trial). As with a grand jury, the Judiciary Committee can compel the production of documents and command witnesses to appear and offer sworn testimony.

It is a common misconception that to impeach a President is to remove him from office. It only means that the House believes the charges are sufficient to generate a trial in the Senate. Only by approving at least one article of impeachment by a two-thirds vote can the Senate remove the President from office.

As for the case of President Kennedy, the House Committee on the Judiciary was authorized in the late summer of 1965 to consider the specifics and to gather and review the evidence. If deemed sufficient, the committee would write and debate proposed articles of impeachment. If the committee voted them down, that would be that. If committee members voted to send the articles to the floor of the House, a simple majority would impeach the President and send the matter to the United States Senate in January for a trial.

Naturally, it was not that simple. The mere act of considering a President’s impeachment can put the Congress and the executive branch into conflict and even trigger impeachable behavior that did not exist before impeachment was considered. The struggle over the recordings that were made by the White House, for example, became an issue debated by the Judiciary Committee as possibly justifying an article of impeachment.

Since January 1965, the Republican party had controlled the House of Representatives by a single vote, 218-217, making their leader, Gerald Ford, the Speaker of the House. The Republicans also controlled the committee chairmanships. This became extremely important during the impeachment proceedings, because William Moore McCulloch, the Republican representing Ohio’s Fourth District, had replaced the previous chairman of the Judiciary Committee, Emanuel Celler, a Democrat from New York’s Tenth District.

Over the course of any congressional session, seats are commonly vacated by death, disability or personal issues that might cause an incumbent to resign while in office. This usually leads to a special election held within a few months, or the next general election, if that is feasible. Normally these elections have little importance other than being symbolic bellwethers of the electorate’s mood. The years 1965 and 1966 were anything but normal, though, given that House leadership teetered on a virtual tie between the parties.

On October 2, 1965, Edwin Edwards retained Louisiana’s Seventh District for the Democrats after the incumbent T. Ashton Thompson was killed in an automobile accident. This left the House still in GOP control, 218-217. Had Edwards lost, it would have put the Democrats behind by three votes.

However, falling right in the middle of the impeachment debate, in which the Republicans barely controlled the House of Representatives, was another election to be held on November 2, and it had the power to change history.

Ohio’s Seventh District had been Representative Clarence Brown’s since 1939. Brown died on August 23 in a Bethesda hospital, the same day that Gerald Ford declared he would support impeachment hearings. With only two months to campaign, Brown’s son, Clarence “Bud” Brown Jr., was set to run as a Republican against Democrat James Barry. If Barry could defeat the younger Brown, the Democrats would reverse the Republicans’ 218-217 majority in the House. Democrat John McCormack would become the Speaker, and Emanuel Celler would get back control of the Judiciary Committee. The Democrats poured money and volunteers into the campaign, hoping to score an upset win over the late incumbent’s son. In the end, though, Barry simply could not overcome Brown’s name familiarity in such a short campaign, and lost by a margin of 54-46 percent.

The House might still change leadership from Republicans back to Democrats in the future, but not in time to save the President of the United States, if his fate were to be decided along party lines.

Republican Chairman William McCulloch called the House Committee on the Judiciary to order on September 15. Its first order of business was a decision not to allow its impeachment hearings or deliberations to be televised. The decision was on party lines, with McCulloch casting the deciding vote. The GOP, having been stung by the Kennedy charisma going back to his 1960 debates with Richard Nixon and his standout news conference performances, wanted to make sure that TV would not impact their work. Also, the spectacle of the JCAAP hearings was recent enough that it served to end the debate before it started.

Kennedy friend and lawyer Clark Clifford represented the President’s legal team in these proceedings. In 1960, Clifford was a member of Kennedy’s Committee on the Defense Establishment and was appointed in May 1961 to the President’s Foreign Intelligence Advisory Board, which he was chairing when asked to handle the impeachment defense. Over the years, Clifford served frequently as an unofficial White House counsel and sometimes undertook short-term official duties. When the President asked him if he would have any problem leading the defense team, Clifford had answered, “Mr. President, I do not approve of much of what I have read lately, but I know that you have been a good President for this country, and I will gladly defend you on the basis of that record.” Even though Bobby had no choice but to recuse himself officially, he continued to remain his brother’s closest confidante, and worked in an unofficial capacity with Clifford from start to finish.

After settling the rules, the committee attempted to decide the scope of its investigation. Members seemed to focus their main concern on the following issues:

Improper relationships that jeopardized the security of the United States or even the life of the President through reckless behavior.

Undisclosed presidential medical conditions and treatments that could have affected the safety and security of the United States during times of crisis.

Presidential approval and encouragement of extralegal activities of the CIA and the FBI.

In addition to these areas of interest, it was also up to committee members to seek all relevant testimony and evidence.

From a testimony point of view, it was decided to bring no woman before the committee simply on the basis of her having engaged in sexual relations with Kennedy, whether inside or outside the White House. Members also decided to bring no cases before the committee that had occurred before January 20, 1961, ruling out a great deal of what was in the FBI files. The decision did, however, leave in some difficult cases, including those of Ellen Rometsch, Judith Campell and prostitutes such as Suzy Chang, who were not U.S. citizens. Even Democrats on the committee were forced to reluctantly agree to investigate these cases.

Where Republicans and Democrats sparred the most was on the issue of the young women who were White House employees and were involved in relationships with the President. The laws in the 1960s were undefined about what constituted an improper workplace environment, and it seemed clear that none of these young women were physical threats to the President. All were known by the Secret Service agents on duty. Republicans wanted these women interviewed by counsel at the very least and got their way with their one-vote majority.

There was also the question of whether Kennedy had abused his presidential power by using Kenneth O’Donnell, David Powers or Evelyn Lincoln to procure or schedule the women involved in these sexual liaisons. All were fair game for compelled testimony, the committee ruled.

The medical condition of President Kennedy was another matter. There was no specific law to prevent a President from lying to the American people about his health, but if the President could be shown to have directed his personal physician to lie about his records, that would be another matter. There was also the issue of what drugs Kennedy was taking when, and whether or not they could have clouded his judgment at crucial times, such as during his meetings with Khrushchev or the Cuban Missile Crisis. All records were then subpoenaed. Dr. Janet Travell and Dr. Max Jacobson would be brought before the committee.

The third leg of potential charges was perhaps the trickiest of all. It involved the role of the President in overseas assassinations and coups in the Congo, Vietnam, Cuba and other countries. In some of these cases, if not most, the CIA had pushed for action that Kennedy had reluctantly agreed to, but as chief executive, the responsibility was his. Even FBI wiretaps of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., had been approved because Hoover wanted them and the Kennedys had agreed in order to keep their own vulnerabilities secret.

Then there was the larger issue of which of these conceivable charges could have generated possible assassination plots against Kennedy. Clearly, sleeping with a mobster’s girlfriends could have triggered a reaction. Approving plots to kill Castro could likewise have triggered counter-plots to kill Kennedy.

William Foley, the general counsel to the Committee on the Judiciary, knew better than most that Ford’s deadline was crushing and nearly impossible to meet. He saw two possible solutions: The committee would have to narrow the focus early, and it would have to fight the White House for the presidential recordings of Oval Office conversations.

“I believed that the committee would have to pick and choose its battles carefully, deciding which charges were most likely to lead to an article of impeachment in advance, and then investigate,” said Foley, “rather than cast a wide net and see what we caught.” In other words, they would have to make full use of what the Joint Committee on the Attempted Assassination of the President and the Warren Commission had learned, plus the journalistic output spawned by the FBI file leak, rather than start from scratch. The committee’s investigation would have to be supplementary and not primary, whenever possible.

Most importantly, thought Foley, committee members would have to get their hands on the White House recordings that Secret Service Special Agent Robert Bouck had disclosed before the Joint Committee on the Attempted Assassination of the President. Chairman McCulloch agreed, and asked Foley and his lawyers to prepare for battle.

The White House was served with a subpoena requesting all recordings and responded that the request was too broad. The committee narrowed the request to a list of forty-five days’ worth of tapes and was told by the White House that it would not comply, based on the concept of executive privilege.

The battle was on. Chairman McCulloch met the press on the Capitol steps to complain, “If the President did not want Congress to hear what is on these recordings, he should not have made them in the first place. They are evidence, and we are prepared to fight for them.”

The Supreme Court agreed to hear the case immediately, because of its importance to the nation. Once again, Chief Justice Earl Warren was in the middle of the President’s affairs. Once again, he refused to recuse himself.

For three days running, lawyers for the executive and legislative branches of the government made their arguments. The White House certainly had possession of the tapes, that much was clear, but having created them, the question could now legitimately be raised in a democracy as to who really owned them? Particularly when they were considered crucial in a showdown between the two branches. The justices were heavily involved, asking dozens of sharp questions.

In the end, the Court ruled 6-3 that the tapes must be turned over. Warren wrote the majority opinion:

Presidential power is not absolute, but proportionate, and must exist within the framework of three-branch government. Checks and balances are real, and the executive branch may not deny the legislative branch evidence without sharing direct cause. The simple claim of privilege is not sufficient.

On the afternoon of November 5, 1965, White House lawyer Clark Clifford informed Chairman McCulloch and General Counsel Foley that he had conducted his own review and found that the White House could not comply with the Supreme Court request. It was not because he did not recognize the ultimate authority of the Court or the committee, he said, but because the tapes apparently no longer existed.

While this conversation was taking place, New York was plunged into darkness, the result of a faulty power grid that threatened the entire East coast. Staff Director Bess E. Dick interrupted the meeting shortly after 5:30 p.m. with the news. It was best for everyone to head home to their families while they still could; the legal wrangling would have to wait until later. It's unlikely that anyone in the room missed the obvious metaphor: This crisis, too, was about to bring the entire system down, if the players were not careful.

As it turned out, power was restored by 7 a.m. the next day across most of the affected areas, and in Washington, D.C., the lights remained on throughout. By 9:30 a.m., Kennedy aide Dave Powers had received a second subpoena, asking him to return to the committee the very next morning. Powers had already testified on charges that he had procured prostitutes for President Kennedy and had used his authority to prevent the Secret Service from doing its due diligence in vetting their identities and examining purses for drugs or weapons.

During that testimony, Powers had exercised his Fifth Amendment right to remain silent to all questions that were asked of him. Earlier, Powers had made news by first refusing to testify at all, but he had changed his mind on the advice of Attorney General Robert Kennedy.

Now the attorney general had to discuss the situation with the President. “Where are these damned tapes, Bobby?” Kennedy had asked. He was informed that Powers had destroyed them. All of them. RFK had retrieved them all from their storage, sent them to Powers’ office, and asked him to begin reviewing them from the moment the committee had asked for them.

Reconstructing the scene in his 1974 book,

Flashpoints

, Robert Kennedy recalls his brother delivering the following words cautiously:

“Dave would never destroy those tapes on his own. We both know that.”

The attorney general chose his own words carefully. “I have just spoken to Dave, and it is his testimony that he took this action on his own volition in an obviously misguided attempt to protect the office of the presidency.”

“They’ll hold him in contempt. He’ll go to prison,” the President said. Jack Kennedy and Dave Powers had been friends going back to the first campaign for Congress in 1946.

“He knows,” Bobby said. “Under no circumstances should you contact him. My advice is that you must fire him immediately before he testifies tomorrow.”

Dave Powers was fired by the White House that afternoon. The next morning he went to Capitol Hill and appeared again before the House Committee on the Judiciary. Rather than take the Fifth Amendment again, he read the following statement:

On October 13, 1965, I removed all of the boxes containing the audio tapes recorded in the White House during the presidency of John Kennedy. I did so with authorization papers on which I forged all necessary signatures. I took this action completely on my own. No one told me to do this, and I specifically state that this action was not taken at the directive of President Kennedy, Attorney General Robert Kennedy, Kenneth O’Donnell, Clark Clifford, nor any other member of the White House staff. I drove these tapes myself to a location in Virginia and supervised their destruction by burning. While this may not be the wish of the committee nor President Kennedy, I have taken this action on my own and am solely responsible.

The Judiciary Committee responded with fury. All of their questions were met by Powers once again invoking the Fifth Amendment. Powers was held immediately in contempt. He was later indicted for lying to Congress and convicted. Powers was sentenced to seven years in prison and fined $100,000.

This case has been hotly debated ever since. Many believe, as President Kennedy apparently did, that Powers would not have acted on his own. Yet he never spoke again on the subject, and his statement to the committee stands as his only comment. Many committee members felt that his actions seemed like prima facie evidence of criminality. West Virginia’s Arch Moore Jr. was most outspoken: “The only reason one man agrees to go to jail is to keep another man from going.”

The closest anyone ever came to a link to the White House was the admission by Kenny O’Donnell, who recalled that he had angrily said, “Somebody ought to burn those fucking tapes!” when the issue was first introduced. O’Donnell insisted, however, that he was not proposing a serious action but simply expressing his frustration at the process and how the tapes had become such a focus of the committee.

Yet the committee was instructed by its counsel that it could draw no conclusions about President Kennedy or the facts based on Powers’ action. It did, however, have an extremely negative impact on the mood of everyone serving.

President Kennedy addressed the issue. “I have never advocated the destruction of evidence on any matter that has come before me in this White House. Mr. Powers, who has been a longtime friend, says he committed this act on his own. I know him to be a truthful man, and I have to take him at his word.”