The 30 Day MBA (36 page)

Authors: Colin Barrow

CASE STUDY

When Mark Zuckerberg, then aged 20, started Facebook from his college dorm back in 2004 with two fellow students, he could hardly have been aware of how the business would pan out. Facebook is a social networking website on which users have to put their real names and e-mail addresses in order to register; then they can contact current and past friends and colleagues to swap photos, news and gossip. Within three years the company was on track to make $100 (£64/â¬72) million sales, partly on the back of a big order from Microsoft that appears to have set its sights on Facebook as either a partner or an acquisition target.

Zuckerberg, wearing jeans, Adidas sandals and a fleece, looks a bit like a latter-day Steve Jobs, Apple's founder. He also shares something else in common with Jobs. He has a gigantic intellectual property legal dispute on his hands. For three years he has been dealing with a law suit brought by three fellow Harvard students who claim, in effect, that he stole the Facebook concept from them.

However, the granting of a patent doesn't mean that the proprietor is automatically free to make, use or sell the invention him- or herself, since to do so might involve infringing an earlier patent that has not yet expired.

A patent really only allows the inventor to stop another person using the particular device that forms the subject of the patent. The state does not guarantee validity of a patent either, so it is not uncommon for patents to be challenged through the courts.

What you can patent

What inventions can you patent? The basic rules are that an invention must be new, must involve an inventive step and must be capable of industrial exploitation.

You can't patent scientific/mathematical theories or mental processes, computer programs or ideas that might encourage offensive, immoral or antisocial behaviour. New medicines are patentable but not medical methods of treatment. Neither can you have just rediscovered a long-forgotten idea (knowingly or unknowingly).

If you want to apply for a patent, it is essential not to disclose your idea in non-confidential circumstances. If you do, your invention is already âpublished' in the eyes of the law, and this could well invalidate your application.

Copyright

Copyright gives protection against the unlicensed copying of original artistic and creative works â articles, books, paintings, films, plays, songs, music, engineering drawings. To claim copyright, the item in question should carry this symbol: © (author's name) (date). You can take the further step of recording the date on which the work was completed, for a moderate fee, with the Registrar at Stationers' Hall. This, though, is an unusual precaution to take and probably only necessary if you anticipate an infringement.

Copyright protection in the UK lasts for 70 years after the death of the person who holds the copyright, or 50 years after publication if this is later.

Copyright is infringed only if more than a âsubstantial' part of your work is reproduced (ie issued for sale to the public) without your permission, but since there is no formal registration of copyright the question of whether or not your work is protected usually has to be decided in a court of law.

Designs

You can register the shape, design or decorative features of a commercial product if it is new, original, never published before or â if already known â never before applied to the product you have in mind. Protection is intended to apply to industrial articles to be produced in quantities of more than 50. Design registration applies only to features that appeal to the eye â not to the way the article functions.

To register a design, you should apply to the Design Registry and send a specimen or photograph of the design plus a registration fee (currently £90). The specimen or photograph is examined to see whether it is new or original and complies with other registration requirements. If it does, a certification of registration is issued which gives you, the proprietor, the sole right to manufacture, sell or use in business articles of that design.

Protection lasts for a maximum of 25 years. You can handle the design registration yourself, but, again, it might be preferable to let a specialist do it for you. There is no register of design agents, but most patent agents are well versed in design law.

Trademarks and logos

A trademark is the symbol by which the goods or services of a particular manufacturer or trader can be identified. It can be a word, a signature, a monogram, a picture, a logo or a combination of these.

To qualify for registration the trademark must be distinctive, must not be deceptive and must not be capable of confusion with marks already registered. Excluded are misleading marks, national flags, royal crests and insignia of the armed forces. A trademark can apply only to tangible goods, not services (although pressure is mounting for this to be changed).

To register a trademark, you or your agent should first conduct preliminary searches at the trademarks branch of the Patent Office to check there are no conflicting marks already in existence. You then apply for registration on the official trademark form and pay a fee (currently £200). Registration is initially for 10 years. After this, it can be renewed for periods of 10 years at a time, indefinitely.

It isn't mandatory to register a trademark. If an unregistered trademark has been used for some time and could be construed as closely associated with a product by customers, it will have acquired a âreputation', which will give it some protection legally, but registration makes it much simpler for the owners to have recourse against any person who infringes the mark.

Names

Business and domain names involve a cross-section of IP issues. A good name, in effect, can become a one- or two-word summary of your marketing

strategy; Body Shop, Toys âR' Us, Kwik-Fit Exhausts are good examples. Many companies add a slogan to explain to customers and employees alike âhow they do it'. Cobra Beer's slogan âUnusual thing, excellence' focuses attention on quality and distinctiveness. The name, slogan and logo combine to be the most visible tip of the iceberg in a corporate communications effort and as such need a special effort to protect.

Business name

When you choose a business name, you are also choosing an identity, so it should reflect:

- who you are;

- what you do;

- how you do it.

Given all the marketing investment you will make in your company name, you should check with a trademark agent whether you can protect your chosen name (descriptive words, surnames and place names are not normally allowed except after long use). Also, check if the name is one of the 90 or so âcontrolled' names such as bank, royal or international for which special permission is needed. Limited companies have to submit their choice of name to the Companies Registration Office along with the other documents required for registration. It will be accepted unless there is another company with that name on the register or the Registrar considers the name to be obscene, offensive or illegal.

Registering domains

Internet presence requires a domain name, ideally one that captures the essence of your business neatly so that you will come up readily on search engines and is as close as possible to your business name. Once a business name is registered as a trademark (see earlier in this chapter), you may (as current case law develops) be able to prevent another business from using it as a domain name on the internet.

Registering a domain name is simple, but as hundreds of domain names are registered every day and you must choose a name that has not already been registered, you need to have a selection of domain names to hand in case your first choice is unavailable. These need only be slight variations, for example Cobra Beer could have been listed as Cobra-Beer, CobraBeer or even Cobra Indian Beer, if the original name was not available. These would all have been more or less equally effective in terms of search engine visibility.

Help and advice on intellectual property matters

- UK Intellectual Property Office (

www.ipo.gov.uk

) has all the information needed to patent, trademark, copyright or register a design. - International intellectual property information at: European Patent Office (

www.epo.org

), US Patent and Trade Mark Office (

www.uspto.gov

) and the World Intellectual Property Association (

www.wipo.int

). - The Chartered Institute of Patents and Attorneys (

www.cipa.org.uk

) and the Institute of Trade Mark Attorneys (

www.itma.org.uk

), despite their specialized-sounding names, can help with every aspect of IP, including finding you a local adviser. - The British Library (

www.bl.uk

> Collections > Patents, trade marks & designs > Key patent databases) links to free databases for patent searching to see if someone else has registered your innovation. The library is willing to offer limited advice to enquirers. - Guidance Notes entitled âIncorporation and names' are available from Companies House (

www.companieshouse.gov.uk

> Guidance).

- Schools of economic thought

- Market structures and competition

- Managing growth

- Understanding business cycles

- Fiscal and monetary policy considerations

- Assessing economic success

E

conomics has been

something of a backwater subject but the crisis that hit the global economy at the end of the first decade of the 21st century changed all that. There is hardly anyone in business who hasn't heard and felt the clash between the Keynesian view that economies need occasionally to be kick started and that of the Monetarists who claim most problems with economies can be solved with a liberal injection of cash â quantitative easing. In fact, as by 2010/11 it had become evident from the contrasting behaviour of governments around the world all heavily armed with schools

of their own economist, there is no conclusive universally applicable strategy

for managing economies. Gordon Brown, the British Prime Minister who claimed to have banished boom and bust, was proved decisively wrong. Perhaps the best way to appreciate why economists never agree lies in this quote by Maynard Keynes: âWhen the facts change I change my mind.'

The jury is out on who the got the whole subject of economics under way, but two serious contenders are Aristotle (382â322

BC

) who, in his work

Topics

, got the subject of human production under way, and Chanakya, whose treatise Arthasastra (economics), written in the period 321â296

BC

, laid out a framework for the economic management of India's agriculture, forestry, wildlife, mining, transport and trade.

Alfred Marshall, the dominant figure in British economics until his death in 1924, defined economics in his influential textbook

Principles of Economic

s

as: âa study of mankind in the ordinary business of life; it examines that part

of individual and social action which is most closely connected with the attainment and with the use of the material requisites of well-being. Thus it is on one side a study of wealth; and on the other, and more important side, a part of the study of man.' Today that definition has been shortened in most textbooks on the subject to: âEconomics is the social science which examines how people choose to use limited or scarce resources in attempting to satisfy their unlimited wants.'

The dismal science, as economics is often referred to, reveals something of the contradictions inherent in the subject itself. Science to most people means a subject comprising fundamental truths that hold good under all conditions and forever. Two and two equals four, or the area of a circle = Ïr

2

, work equally as well as propositions in Mongolia and on the Moon. But put two economists together and you will get three economic theories. Worse still, if you put three together you could end up with six!

Groups of economists who broadly share the same views are collectively known as schools. Thinking of these as places where people are learning about a constantly changing dynamic subject is a more useful concept than considering economics to be a science. With Buddha seeking to eliminate want, Malthus who was sure that human populations grew faster than food production and so charity was self-defeating, Marx and Keynes who for different reasons saw the state's role as central and Adam Smith whose âInvisible Hand' saw all economic activity as being subject to the law of unintended consequences, there has been and is some scope for diversity.

The two economic theories that every self-respecting MBA must have an appreciation of are:

- Keynesian: A theory of macroeconomics developed by British economist John Maynard Keynes and documented in his book

The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money

, published in 1936. He argued that low demand is the primary cause of recessions and that government fiscal policies (see below) should be the method employed to create employment, control inflation and stabilize business cycles. This work initiated the modern study of macroeconomics and guided economic thinking, only diminishing in popularity in the 1970s when violent shocks to economies, caused particularly by escalating oil prices, simultaneously led to high unemployment and high inflation rates. This challenged the central implications of Keynesian economics. - Monetarist: First put forward by the economist Milton Friedman and the Chicago school of economists. Friedman and Anna Schwartz (an economist at the US National Bureau of Economic Research) in

their book

A Monetary History of the United States 1867â1960

argued that âinflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon'. Friedman advocated that a country's central bank should pursue a monetary policy (see below) such as to keep the supply of and demand for money at equilibrium. By 1990 monetarism was being challenged as it could not be reconciled with, among other things, the inability of monetary policy alone to stimulate the economy in the 2001â03 period.

Marxism: âDas Kapital, Kritik der politischen Okonomie'

(

Capital: Critique of Political Economy

), published in 1887 in its first English edition is a critical analysis of capitalism as an economic force. It set out to show that the economic laws of the capitalist mode of production were basically flawed. In the second best-selling book of all time,

The Communist Manifesto

, Marx and his co-author Engels wrote: âWhat the bourgeoisie therefore produces, above all, are its own grave-diggers. Its fall and the victory of the proletariat are equally inevitable.'

Marxism claims that labour is the only economic factor entitled to earn money and that those with capital should not be able to receive an income as interest on their savings or investments. In any period of history, dominant and subservient classes, according to Marxism, can be identified by their inequality in wealth and power. Marx saw this as a fundamental moral problem and argued that while capitalism continued to operate, some groups would dominate others and take for themselves the lion's share of the society's wealth, power and privileges. The ultimate goal of Marxism is a classless society where everyone is equal. Marx believed that history is in essence concerned with the struggle between classes for dominance: âThe history of all hitherto existing society is the history of class struggles.'

While conventional economics, that is the capitalist versions of the subject, believe Marxism is dead and buried in Highgate cemetery, the citizens of the most populous and successful nation on earth in economic terms at least â the Chinese â may beg to disagree. They are not alone. A recent Reuters reports cited a survey of east Germans found that 52 per cent believed the free-market economy was âunsuitable' and 43 per cent said they wanted socialism back.

You can find out more about how economic thought has developed over the years at these websites:

http://en.citizendium.org/wiki/History_of_economic_thought

and

www.timelinesdb.com/listevents.php

.

Microeconomics is the study of economics as it affects small units such as individuals, families, firms and industries. Macro is a study of the forces that affect a whole economy. The main concept used in microeconomics, and one that underpins almost the whole subject of economics, is that of the price elasticity of demand. The concept itself is simple enough. The higher the price of a good or service the less of it you are likely to sell. Obviously it's not quite that simple in practice; the number of buyers, their expectations, preference and ability to pay, the availability of substitute products also have an effect.

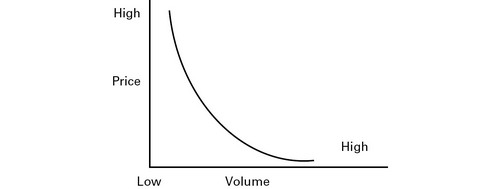

Figure 7.1

is that of a theoretical demand curve.

FIGURE 7.1

Â

The demand curve

The figure shows how the volume of sales of a particular good or service will change with changes in price. The elasticity of demand is a measure of the degree to which consumers are sensitive to price. This is calculated by dividing the percentage change in demand by the percentage change in price. If a price is reduced by 50 per cent (eg from $/£/â¬100 to $/£/â¬50) and the quantity demanded increased by 100 per cent (eg from 1,000 to 2,000), the elasticity of demand coefficient is 2 (100/50). Here the quantity demanded changes by a bigger percentage than the price change, so demand is considered to be elastic. Were the demand in this case to rise by only 25 per cent, then the elasticity of demand coefficient would be 0.5 (25/100). Here the demand is described as being âinelastic' as the percentage demand change is smaller than that of the price change.

Having a feel for elasticity is important in developing a business's marketing strategy, but there is no perfect scientific way to work out what the demand coefficient is; it has to be assessed by âfeel'. Unfortunately, the price elasticity changes at different price levels. For example, reducing the price of vodka from $/£/â¬10 to $/£/â¬5 might double sales, but halving it again may not have such a dramatic effect. In fact it could encourage one group of buyers, those giving it as a present, to feel that giving something that cheap is rather insulting.

The whole of the subject of economics as practised in advanced economies is predicated on the belief that market forces are allowed a large degree of

freedom. New firms can set up in business, charging the price they see fit, and if their strategy is flawed they will be allowed to fail (see also Chapter 8, Entrepreneurship). Price is allowed to send important signals throughout the economy, apportioning demand and resources accordingly. But perfect competition, where price is allowed such freedom, is only one of four prevailing market structures; although market economies are dominated by near-perfect competition, that is not maintained without a struggle.

The following are the four market structures that are at work in economies.

Monopoly

Monopolies exist where a single supplier dominates the market and so renders normal competitive forces largely redundant. Price, quality and innovation are compromised, so deliver less value to the end consumer than they might otherwise expect. Microsoft has a near-monopolistic grip on the operating system market, as has Pfizer, the pharmaceutical giant, through its patent on the drug Viagra; and British Airports Authority (BAA), which runs Heathrow, Gatwick and Stansted, has a similar hold on London airports' traffic.

Monopolies claim that without being allowed to dominate their market it would be impossible to get sufficient economies of scale to reinvest. That was the argument of the early railway companies and it was BAA's argument in 2008 in defending itself against the prospects of a government-enforced break-up.

In countries where monopolies are seen as being detrimental, bodies exist to regulate the market to prevent them becoming too powerful. The UK has the Competition Commission (

www.competition-commission.org.uk

), the United States the Federal Trade Commission (

www.ftc.gov

) and the EU has The European Commission (

http://ec.europa.eu/comm/competition/index_en.html

), all keeping monopolies in check. A duopoly is, as the name would suggest, a particular form of monopoly with only two firms in the market.

Oligopoly

This is where between 3 and 20 large firms dominate a market, or where 4 or 5 firms share more than 40 per cent of the market. The danger for consumers and suppliers alike is that these dominant firms can control the market, to their disadvantage. Supermarket chains in the UK, airlines, oil exploration and refining businesses the world over operate as virtual oligopolies. Frequently the temptation to act in a cartel to fix prices is too great to resist. BA had colluded with Virgin Atlantic on at least six occasions between August 2004 and January 2006, the Office of Fair Trading said.

Between August 2004 and January 2006, British Airways and Virgin Atlantic, the dominant players on the route from London to US cities,

colluded with each other to fix the price of fuel surcharges. During that time, surcharges rose from £5 to £60 per ticket. British Airways had to set aside £350 million to deal with fines in the UK and United States.

Perfect competition

This is a utopian environment in which there are many suppliers of identical products or services, with equal access to all the necessary resources such as money, materials, technology and people. There are no barriers to entry, so businesses can enter or leave the market at will and consumers have perfect information on every aspect of the alternative goods on offer.

Competitive markets

Sometimes referred to confusingly as monopolistic competition, this rests between oligopoly and perfect competition, but is closer to perfect competition. Here a large number of relatively small competitors, each with small market shares, compete with differentiated products satisfying diverse consumer wants and needs.