The Air-Raid Warden Was a Spy: And Other Tales From Home-Front America in World War II (29 page)

Read The Air-Raid Warden Was a Spy: And Other Tales From Home-Front America in World War II Online

Authors: William B. Breuer

Tags: #History, #Military, #World War II, #aVe4EvA

After his return, Dyess was promoted several grades to lieutenant colonel, then put in a deep freeze to keep him away from media types. A decision had been made at the highest level—presumably by President Roosevelt—to hide Dyess’s account.

In weeks ahead, heavy pressure was mounted for the Roosevelt administration to release full details of the report. In Texas, the officer’s father was seething with anger, making scathing remarks about “pencil-pushing generals in Washington who would faint if they smelled gunpowder.”

On January 28, 1944, newspapers across the land published banner headlines and stories giving complete details of the Dyess document. More than five thousand Americans had died of starvation and torture at the hands of the Japanese after having been captured on Bataan and Corregidor in early 1942.

Home-front America was stupefied by the news. On the Senate floor in Washington, Missouri Senator Bennett Champ Clark thundered a demand to “bomb Japan out of existence.” Georgia Senator Richard B. Russell loudly called for hanging Emperor Hirohito as a major war criminal. Many other members of Congress expressed similar sentiments.

From Portland, Oregon, to Portland, Maine, the battle cry “Remember Pearl Harbor” was no longer merely a slogan. Now Americans were demanding that Japan be wiped off the map.

29

War Hero Bounced from Air Corps

F

OR MORE THAN A YEAR,

Air Corps Staff Sergeant Clifford Wherley had been risking his life almost daily as a turret gunner in a Marauder bomber. After flying twenty-one combat missions in North Africa, Sicily, and Italy, he had earned the Air Medal with three oak-leaf clusters.

Suddenly, he was ordered to return to the United States immediately. Over his vigorous protests, he was given an honorable discharge and sent home. It had been discovered that the sergeant was still barely sixteen years of age.

30

An Overseer of GI Morals

T

OWARD THE CLOSE OF 1943,

millions of American servicemen were stationed around the world. Because the real item was usually unavailable, the GIs substituted pictures of statuesque beauties clipped from newspapers and magazines. They plastered barracks, Quonset huts, even the insides of helmets with these pictures. Without doubt, the two most popular ones were Hollywood movie sirens Rita Hayworth in a flimsy nightgown and Betty Grable in a swimsuit.

Almost as popular with the homesick GIs were the sultry paintings of curvaceous young women dressed in diaphanous costumes that appeared each month in Esquire magazine. None of these paintings revealed any more than could have been seen at any American swimming pool. But in early 1944, Postmaster Frank C. Walker decided that these images of sexy ladies tended to corrupt the morals of America’s clean-cut young servicemen.

Walker appointed himself as a sort of Overseer of GI Morals and banned Esquire from the mail. Thus he firmly established himself among servicemen as the most despised human, ranking slightly behind Adolf Hitler.

One sailor expressed the indignation of the uniformed masses when he wrote to his senator: “Who in the hell got the bright idea of banning pictures. I, for one, have more than fifteen of them, and none of them seem to demoralize me in the least. What will these ignorant specimens back in the States think up next? I wish these high-browed monkeys could spend a year overseas without a magazine to look at.”

In Washington, top-level officials quietly quelled the global protest by rescinding the Esquire ban, thereby abolishing the implied post of Overseer of GI Morals that Postmaster Walker had assumed.

31

Top-Secret Projects Opened to Women

145

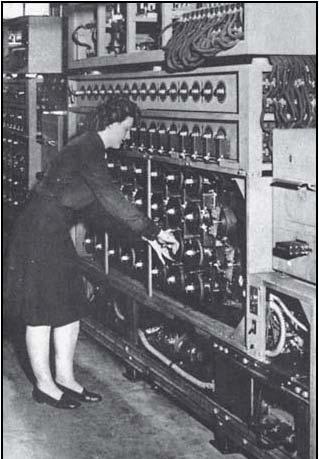

A WAVE tends to a top-secret marvel that decoded intercepted coded German messages in Europe. This scene was at the Nebraska Avenue station in Washington, D.C. (National Security Agency)

Top-Secret Projects Opened to Women

A

LTHOUGH WACS

and Army and Navy nurses were on active duty in many parts of the world as 1943 drew to a close, the law prohibited WAVES, SPARS, and Women Marines from duty stints outside the United States. Yet these thousands of females were making significant contributions to the war effort on the home front.

At Cherry Point, North Carolina, 80 percent of the control-tower operations at the Marine Air Station were handled by women marines. WAVES serving in naval aviation taught instrument flying, aircraft gunnery, and celestial navigation.

WAVE officers and SPAR officers, nearly all of them university graduates, were involved in finance, chemical warfare, and aerological engineering. At Norfolk, they helped install sophisticated radar on aircraft carriers and other warships.

For the first time, top-secret projects were opened to military women. Both the Navy and the Coast Guard utilized females in Long-Range Aid to Navigation (LORAN) stations, and WAVES were involved in a night-fighter training course. At a hidden communications center in Washington, D.C., WAVE officers spent countless hours staring at electronic screens, watching for “blips.” It was boring, seemingly senseless work; the women had never been told the reasons for their job. When they were finally informed that each blip represented a U.S. ship being sunk, the task took on meaning and morale soared.

WAVE Lieutenant Mary Osborne was assigned to a supersecret Naval Intelligence facility in Washington. Her job had its roots back to mid-1939, just before England went to war with Nazi Germany. British scientists had cracked the Enigma code, which was used by the German armed forces and diplomats to send wireless messages. Adolf Hitler and other leaders were convinced that the code was unbreakable.

Throughout the war, the British intercepted the German messages and gave the code name Ultra to all intelligence gathered from Enigma. British Prime Minister Winston Churchill had agreed to share the Ultra information with the United States, so Mary Osborne and her WAVE colleagues were receiving this information by wireless from England for transmittal to government and military leaders in Washington.

32

Roosevelt: Chloroform Drew Pearson

O

N HIS WEEKLY BROADCAST

from New York City, muckraking columnist Drew Pearson ignited an uproar on home-front America. He gave a garbled and highly exaggerated account of how Lieutenant General George S. Patton Jr., a hero in the United States after his brilliant victories in North Africa, had slapped an enlisted man, a court-martial offense. It was November 12, 1943.

Back on August 10, Patton had visited the 93rd Evacuation Hospital in Sicily and became enraged to find a nonbattle casualty. “It’s my nerves, sir,” the weeping GI muttered. “I can’t stand any more shelling.”

Patton, widely known for his short fuse, exploded, calling the soldier a “yellow bastard” and slapping him with a glove. “There’s no such thing as battle fatigue,” Patton screamed. “Only goddamned cowards!”

Reportedly a nurse in the 93rd Evac told her boyfriend, a captain in public affairs, about the episode and he passed it along to correspondents assigned to Patton’s Seventh Army.

Collectively, the reporters in the Mediterranean agreed to sit on the explosive story for the time being. But they sent Demaree Bess of the Saturday Evening Post, Merrill Mueller of NBC radio, and Quentin Reynolds of Collier’s to call on General Dwight Eisenhower.

Eisenhower told the three journalists that he had severely reprimanded Patton, had relieved him of command of the Seventh Army, and suggested that he apologize to the troops for his unacceptable behavior. His only goal, Eisenhower explained, was to retain Patton, his boldest combat leader, for the battles that lay ahead in Europe.

Based on Eisenhower’s actions, all correspondents decided to keep mum, and the episode remained unknown on home-front America until Drew Pearson’s broadcast.

An Ace German Operative

147

Taking their cue from Pearson, newspapers around the United States erupted in a barrage of blaring headlines. The New York Sun ran a three-column, page-one picture of a scowling Patton under the headline:

STRUCK SOLDIER

. Vicious editorials were rampant.

In Congress, members fell over one another in their eagerness to take the floor and denounce Patton. A few demanded that he be stripped of his rank and thrown out of the Army.

While the Patton controversy was swirling, President Roosevelt declined public comment. But he made it known to confidants how he felt about Drew Pearson: “I’m all for chloroforming him!”

33

An Ace German Operative

I

N LATE JANUARY 1944,

a German spy operating a shortwave radio station outside New York City flashed a message to his controllers in Hamburg, Germany. From an “unimpeachable source,” the covert agent stated, he had learned that the Americans were planning to launch an invasion of the Kurils, a chain of Japanese governed islands stretching from Hokkaido, Japan, northeast for a few hundred miles.

As the German spy knew would be the case, Hamburg relayed the information to intelligence officers in Tokyo. Actually, the message was a hoax. The German was working for the Federal Bureau of Investigation, which had given him the code name of ND98.

An element of a large American armada that was forming for an invasion would make a feint at the Kurils, but the true target was Kwajalein, a strongly defended atoll in the Marshall Islands in the central Pacific Ocean.

Back in mid-1941, ND98, who had been operating an import-export firm in Germany, was summoned to the Abwehr office in Hamburg. A stern Nazi official told him that he was going to go undercover for the Third Reich in South America, where a widespread German espionage network was entrenched. He was told to set up a radio transmitter and was handed the code names of three people who would send him information concerning war production from the United States.

Two weeks later, ND98 arrived in Montevideo, Uruguay. When he was certain that Nazi agents weren’t tailing him, he arranged to meet with a U.S. State Department official and offered his services.

Several days later, the German advised his bosses in Hamburg: “Unable to establish radio station. Am going to United States where I will be able to operate more freely. Will contact you.”

Flying into New York City, ND98 was met by two FBI agents and escorted to a nearby hideout where he made radio contact with Hamburg on February 20, 1942.

Soon ND98 started feeding high-grade intelligence to Germany—information painstakingly prepared by FBI operatives and screened or furnished by the Joint Security Council that operated under the direction of the Joint Chiefs of Staff in Washington.

More than a year later, in August 1943, officials at the Hamburg post complained that while ND98’s intelligence had been good, it was quite expensive. Presumably Hamburg had been getting heat from Berlin to trim its budget. By now the Nazis had paid him some $34,000 (equivalent to about $400,000 in 2002), which was handed over to the Alien Property Custodian.

ND98’s FBI handlers decided to be outraged. So he sent a message: “Sorry you regard information as too expensive. If not satisfactory, will be glad to withdraw.”

As the FBI had anticipated, Hamburg immediately assured their ace operative that not only was his production highly satisfactory, but he would soon receive a $20,000 bonus.

ND98 acknowledged receipt of the hefty bonus with the message about the phony Kurils invasion.

Later the Joint Chiefs of Staff told FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover that the fake intelligence received in Tokyo from Hamburg had contributed to the success of the invasion of the Marshall Islands in February 1944.

34

Part Five

On the Road to Victory

Hoodwinking Hitler from New York

D

URING THE EARLY MONTHS OF 1944,

thousands of families on home-front America were gripped with anxiety on knowing that loved ones were in England or bound for that destination. Except for an elderly monk who had been living alone for fifty years in a cave high in the mountains of Tibet, the entire world knew that the Allies were mustering a powerful force in the British Isles to cross the English Channel and strike against Nazi-occupied Europe.