The Air-Raid Warden Was a Spy: And Other Tales From Home-Front America in World War II (33 page)

Read The Air-Raid Warden Was a Spy: And Other Tales From Home-Front America in World War II Online

Authors: William B. Breuer

Tags: #History, #Military, #World War II, #aVe4EvA

Bustling New York harbor was the focus for the father-and-daughter spy team, Simon and Marie Koedel. (New York Port Authority)

Nazism, offered his services as a spy to Admiral Wilhelm Canaris, chief of the Abwehr, the intelligence agency.

Koedel was given an exhaustive course on espionage in Hamburg, then told to return to New York City as a “sleeper” and await a call to go into action. It would be in early 1940, four years later, when the summons to duty came. The lean, gaunt, humorless “sleeper” was being activated as Abwehr Agent A-2011. He was given a commission as a captain and was soon promoted to major because of his innovative and highly productive spying activities.

Koedel sought and was granted membership in the American Ordnance Association, a lobby for a strong national defense. Often he strolled brazenly up to the gates of plants, flashed his Ordnance Association card, and was admitted. Sometimes officials took him on a guided tour of what should have been a top-secret facility.

Once he tried this ploy at the Chemical Warfare Center at Edgewood Arsenal, Maryland, where the strictest security measures were employed. There the Army tested its newest hush-hush weapons. Guards would not permit Koedel to enter.

Returning to his drab flat on Riverside Drive, Koedel promptly telephoned an official at the Ordnance Association office in Washington and feigned deep indignation over the treatment he had received at the Chemical Warfare Center.

Stumbling into a World Series

167

The association official contacted a high officer in the War Department and demanded to know why this distinguished chemical engineer (he knew nothing about chemistry), army veteran, and loyal booster of a strong national defense was being barred from Edgewood Arsenal. “You would think Mr. Koedel was a spy!” the executive complained.

Within hours an officer in the War Department read the riot act to the Edgewood Arsenal commander, and Koedel entered the facility and was given a guided tour. Two weeks later, Abwehr officers in Berlin were reading Agent A-2011’s report on what he had seen and been told at the secret arsenal.

These espionage triumphs had been conducted while the United States was not at war. So the most serious penalty Koedel could have received if unmasked was a prison sentence.

In the meantime, Marie Koedel, the daughter, had been playing a highly active espionage role. She covered her waterfront “beat” in New York City almost daily, sauntering into dingy saloons in dresses that left little to the imagination and casting flirtatious glances at the merchant seamen. Soon one or more of the men would join her.

Loose-tongued from booze and seeking to impress the willowy brunette, the seamen told her about departure dates of convoys, their routes, ship armaments, cargoes, and other maritime secrets. Based on Marie’s information and his own connivances, A-2011 kept detailed convoy reports flowing to the Third Reich, from where the data were relayed to U-boat commanders prowling the Atlantic Ocean sea-lanes.

After Koedel’s arrest, Marie Koedel was picked up in New York City by FBI agents. Tried in federal court in Brooklyn, Simon Koedel was sentenced to fifteen years in prison. Marie, whose spying had no doubt resulted in the deaths of many merchant sailors, received a term of only seven and a half years.

13

Stumbling into a World Series

I

N ST. LOUIS IN EARLY SEPTEMBER 1944,

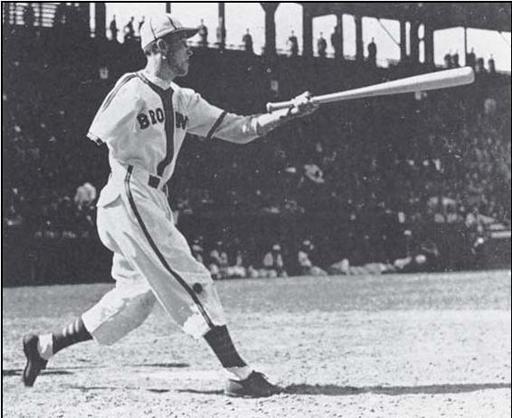

Sportsman’s Park, a stadium rich in baseball lore, was decked out in colorful bunting for the opening of the annual World Series. The teams that had stumbled into the annual fall classic, the St. Louis Browns in the American League and the St. Louis Cardinals in the National League, were so inept that Warren Brown, a sports writer, predicted: “I don’t believe either team can win.”

Soon after Pearl Harbor, President Franklin Roosevelt had felt that major-league baseball would have a positive and morale-boosting role in the momentous years that lay ahead before victory over Japan and Germany was secured. So he had written to Judge Kennesaw Mountain Landis, the baseball commissioner: “I honestly feel that it would be best for the country to keep baseball going.”

Unique even among wartime major-league baseball players was one-armed Pete Gray, who played for the St. Louis Browns. (Author’s collection)

And baseball did “keep going”—but barely. By World Series time 1944, more than three hundred major-league players were wearing military uniforms. They included most of the genuine superstars. Detroit slugger Hank Greenberg had been the first big-name player to sign up soon after America went to war. He volunteered as a private in the Army Air Corps, was commissioned, and saw duty with a B-29 bomber outfit in China as a captain.

“Jolting Joe” DiMaggio, who led the New York Yankees to World Series titles several times and established a record (that still stands) of hitting safely in fifty-six consecutive games, turned in his pin-striped baseball uniform for Army Air Corps khaki and eventually became a staff sergeant serving in Hawaii.

Boston Red Sox slugger Ted Williams, known as the Splendid Splinter because of his gangling build, joined the marines, became a fighter pilot and a captain, seeing heavy action in the Pacific.

“Rapid Robert” Feller, who set strikeout records while pitching for the Cleveland Indians, was a gunner on the battleship Alabama. Warren Spahn, a classy lefty who hurled for the then Boston Braves, received a Purple Heart and a Bronze Star for an heroic action. Spahn was the only major-league baseball player during the war to receive a battlefield commission.

Wartime major-league baseball consisted largely of washed up veterans (like forty-two-year-old Jimmy Foxx who had hit more than five hundred home runs in his prime), players with lesser skills, and rejects of the past. Symbolizing the game’s patchwork quilt was Pete Gray.

A Riot Erupts in New York City

169

Gray had lost his right arm at age six in an accident. Yet, like countless small boys, he dreamed of one day becoming a major-league baseball player. As gently as possible, his father tried to discourage such thoughts or Pete’s spirit would be crushed. Perhaps Pete might get into bowling or tennis, the father had hinted.

Undaunted, the boy pursued his dream. Off in a pasture where he could not be seen, he would spend hours tossing walnuts into the air just above his head, then swinging his broomstick “bat” at the kernel as it came back to the ground. With considerable merit, he felt that if he could gain the knack of connecting with a small nut using a thin broomstick, one day he could hit a much larger baseball with a much larger bat. Soon he became skilled in hitting walnuts.

In his teens and on into manhood, Gray played amateur baseball, and in the wartime year of 1944, he started the season as an outfielder with the professional Memphis team in the Southern Association.

Gray had developed techniques that were not necessary for other players. In the outfield, he caught the ball with his gloved hand, placed the ball against his chest, let it roll out of his glove and up his wrist as he tucked the glove under the stub of his right arm, then drew his left arm back across his chest until the ball rolled into his hand. He had practiced this lightning-like maneuver for countless hours, and could fire the ball back to the infield as rapidly as other players.

Major-league scouts couldn’t believe that a player with only one arm could hit at this level of competition, and they flocked to Memphis to watch Pete play. The attitude of the scouts soon changed, however, when Gray hit a remarkable .333 (one hit in three times at bat) that year. Anything above a .300 batting average is considered to be excellent.

On opening day of the 1945 season, an awed Pete Gray, wearing the uniform of the St. Louis Browns, stepped onto the diamond at Sportsman’s Park. He had signed a contract with a major-league team: his boyhood dream had come true.

At this level of competition, even with mainly wartime-caliber players on the teams, the rookie found pitchers were difficult to hit consistently. In seventy-seven games, Pete sparkled in the outfield and his powerful arm threw out numerous runners trying to take an extra base, but he hit only .218.

Only Pete’s family knew a secret: early in the war he had tried to volunteer for the Army in any capacity, but was politely rejected.

14

A Riot Erupts in New York City

M

ANHATTAN WAS COLD AND BLEAK

on the morning of October 12, 1944, when a ruckus broke out in Times Square. Some thirty thousand frenzied bobby-soxers

stormed the Paramount Theater box office, but only three thousand tickets were available to see and hear a frail crooner with rumpled brown hair named Francis Albert Sinatra.

The crush of mainly teenaged girls snarled traffic, causing a strident cacophony of honking horns and loudly cursing drivers. The mass of flesh trampled luckless passersby and plunged through storefront windows. A force of seven hundred riot police was hastily rushed in to try and restore a semblance of order.

Inside the cavernous Paramount, Frank Sinatra was greeted by squeals of delight from the three thousand girls, most of whom had stayed on the cold sidewalk all night to get tickets. Trumpeted by press agents as the King of Swoon and the Voice that Thrills Millions, Sinatra started singing. His sparkling blue eyes searched the faces in front of him, causing each bobbysoxer to believe that he was vocally romancing her alone. Adolescent voices screamed in ecstasy.

In what may have been an orchestrated promotion by Sinatra’s clever press agents, scores of schoolgirls swooned as the Voice crooned the velvety words of a popular ballad, “All or Nothing at All.” Curiously, ushers happened to be armed with smelling salts and had stretchers to carry “swooners” out of the Paramount—as newspaper cameras clicked.

Twenty-eight-year-old Frank Sinatra was a new phenomenon on the American scene. No other singer, not even the fabled Bing Crosby, had ever inspired such wild adulation.

Adults and most press people were mystified by the hoopla. Newsweek magazine huffed: “As a visible male object of adulation, Sinatra is baffling.”

In an era when the accepted image of a manly American was a brawny soldier in muddy combat fatigues wreaking havoc on the Germans or Japanese, Sinatra did seem to be an unlikely idol. Five feet ten inches tall and weighing only one hundred and thirty-five pounds, the singer seemed to be in danger of collapsing from malnutrition.

Various psychiatrists tried to explain the phenomenon. “Mass hypnotism,” said one. “Mass frustrated love,” guessed another. “Mammary hyperesthesia,” stated yet another, referring to Sinatra’s wispy build, a maternal “urge to feed the hungry.”

Newspaper and magazine columnists had different analyses. With most young men in the service, Frank was the only male around. One critic said of the Sinatra cult: “They’re imbecilic, moronic, screaming-meemie kids.”

Be as it may, the Voice was pulling down a whopping $10,000 (equivalent to some $120,000 in 2002) for each performance at the Paramount. This fee for an hour of singing on stage was more than an entire company of GI infantrymen battling the Germans along the Siegfried Line was being paid per month.

A Riot Erupts in New York City

171

Singer Frank Sinatra received more money for a one-hour gig at New York City’s Paramount Theater than an infantry company fighting in Europe was paid for an entire month. (CBS)