The Anthologist (21 page)

Authors: Nicholson Baker

Tags: #Literary, #Poets, #Man-woman relationships, #Humorous, #Modern & contemporary fiction (post c 1945), #General, #Fiction - General, #General & Literary Fiction, #American Contemporary Fiction - Individual Authors +, #Fiction

I called the federal government of the United States, and a nice woman who worked there made an appointment for me in Boston on Monday morning at nine-thirty.

Y

OU SEE

, this is what I'm up against. This little book here. Published by Farrar, Straus, which publishes Elizabeth Bishop. It's James Fenton,

An Introduction to English Poetry.

Very nice indeed. In it he says some true and interesting things and some false things.

We can't blame him for saying the false things, because he's saying what everybody has always said from the abysm of time. First he says that iambic pentameter is preeminent in English poetry. No it is not. No it is not. Iambic pentameter is an import that Geoffrey Chaucer brought in from French verse, and it was unstable from the very beginning because French is a different stress universe than Middle English and it naturally falls into triplets and not doublets. No, the march, the work song, the love lyric, the ballad, the sea chantey, the nursery rhyme, the limerick--those are the preeminent forms, and all those have four beats to them. "Away, haul away, boys, haul away together, / Away, haul away boys, haul away O." Fenton's own best poems use four-beat lines.

And then Fenton says that iambic pentameter is, quote, "a line of five feet, each of which is a ti-tum. As opposed to a tum-ti."

And that's what they all say. Fenton doesn't know what he knows. He's written beautiful iambic pentameter lines. His ear knows that there's more to it than that. And he is just one of an endless line of people who say that an iambic pentameter line is made up of five feet, or five beats. And it isn't. An iambic pentameter line is made up of six feet. Or rather five feet and one empty shoe--i.e., a rest. Unless the line is forcibly enjambed and then, to my ear, it sounds bad. Keats, bless his self-taught genius soul, came up with some scary enjambments. "My heart aches, and a drowsy numbness pains," next line, "My sense."

B

UT LET'S GET

the Sharpie out. And let's take a look at a real iambic pentameter line. Two of them, in fact, from Dryden. I'm going to write them out for you. This is the couplet that I copied out in my notebook, as I think I mentioned. It's called a heroic couplet--and Dryden was the one who really made it work in English. He forced its preeminence. He used it to write what he called "heroic plays," and he used it to translate Virgil's

Aeneid,

which is about the heroic deeds of gods and men. And after him came Pope and everyone else. The couplet goes like this. I'll sing it.

Now, the way we're taught to talk about these two lines is to say that they are in iambic pentameter. There are two parts to this. First, "iambic." And second, "pentameter."

"Iambic" is a Greek word that in English just means an upbeat. The iambic conductor puffs out his man chest, lifts his batoned hand up, and everybody sees the eighth note hovering there before the bar line on their music stands, and the string tremolo builds, and the mallets of the tympani blur, and the chord swells, and crests, and gets foamy at the ridge, and then the baton comes down and a big green glittering word-wave crashes down on the downbeat. Ya-

ploosh.

Ka-

posh.

"All human things." That's the iamb. It's a kind of sneeze. Iambs can begin four-beat lines or so-called pentameter lines, which are really six-beat lines. "Oh

who

can from this dungeon raise." "A

soul

enslaved so many ways." "And

what

is Art whereto we press." "The

world

is too much with us." "I

met

a man who wasn't there." Let's see, what are some more? "The

wed

ding guest, he beat his breast." "My

lit

tle horse must think it queer." Dang, I keep wanting to use shorter lines as my examples. Which is my point.

But let's see, let's see. "I

should

have been a pair of ragged claws." Prufrock. Iambic pentameter. "When

I

have fears that I may cease to be." Keats, iambic pentameter. "Mere

an

archy is loosed upon the world." Yeats, iambic pentameter. "And

slen

der hairs cast shadows, though but small." Dyer. "If

you

can keep your head when all about you." Kipling. "The

art

of losing isn't hard to master." Elizabeth Bishop. "They

flee

from me who sometime did me seek." Et cetera, et cetera. "Et cetera" is an iambic rhythm, if you pronounce it the way the French do. And iambs are extremely common. The first syllable is an upbeat to the line, and the rhythm is a game of tennis--it's that basic duple rhythm, badoom, badoom, badoom.

Now one problem with "iamb" as a name for this clearly audible upbeat phenomenon is that the word "iamb" isn't iambic, it's trochaic. A trochee is a flipped iamb. It's like a staple-crunch:

crunk

-unk. "Iamb" is trochaic. Isn't that the most ridiculous thing you ever heard? And we've tolerated and taught this impossible Greek terminology for centuries. If iamb were pronounced "I

am

!"--as a counterfactual--it would itself be iambic. "I

am

interested in what you're saying!" "I

am

going to take out the garbage!" "I think therefore I

am

!" You hear that? Then "iamb" would be a decent name for what's going on. Not a great name, but a decent name. But no, it isn't pronounced with the stress on the second syllable. And yet this is what we've got to work with. "Iambic" is the name for this sort of upbeat when it's found in a duple rhythm. Not in a triple rhythm. In a triple rhythm, there's another Greek word you can use, if you're inclined: "anapest." But in a double rhythm, a line that begins with an upbeat is iambic. If you follow me. Just saying all this creates a fog of brain damage.

But so much for the first part of the phrase, "iambic." Just set it and forget it. Don't worry about it. You can change an initial trochee to an iamb by adding an "And" or an "O." And you can flip around an iamb so that the line begins with a little triplet, or an eighth note and a sixteenth note, which happens a lot--as in "Season of mists and mellow fruitfulness." Or "Give me my scallop-shell of quiet." So the whole notion is fluid, and we don't need to dwell on it any longer. Some lines begin with an upbeat and some don't--that's all you need to know about the iamb.

B

UT NOW FOR THE REAL THORNINESS

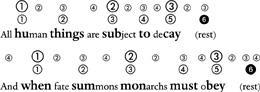

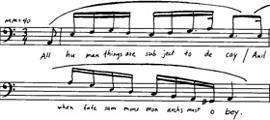

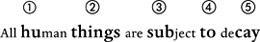

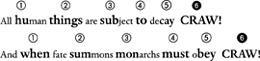

: PENTAMETER. "All human things are subject to decay." That's the line. Then: "And when fate summons monarchs must obey." And you think, Okay, good, I see five stresses there, like five blackbirds on a power line.

Five little blackbirds. Ah, but there's a raven of a rest there at the end that you're not counting, my friend. If you say the two lines together, you'll hear the black raven. Listen for him:

If you leave out those raven squawks--those rests--and you only count the blackbirds on the line, you are not going to be able to say this couplet the way Mr. Dryden meant it to be said. Try it as a run-on. "All-human-things-are-subject-to-decay-and-when-fate-summons--" What? Who? Where am I? You see? It's just not right that way. You cannot have five stresses in a line and then jog straight on to the next line. If you do that, it sounds out of whack. It sounds horrible. It sounds like--enjambment.

Let's take another example of a heroic couplet. This one is from Samuel Johnson. He wrote it for his impoverished drunken friend Oliver Goldsmith.

You've got to have the rests! There's no question about it. If you don't have the rests, you don't have a proper couplet. These are six-beat lines. So-called iambic pentameter is in its deepest essence a six-beat line.

Actually no, I take that back. It's not. In its very deepest, darkest essence it's a three-beat line. Here's where we get to the nub of it. Because people really only hear threes and fours, not sixes. Let's take a look at how this works. And to do it, we're going to up the pace a little bit. We're going to say some of these lines flowingly and fast, listening for the way they truly fall. And as we do, we're going to tap our feet in rhythm. Let's try it. Get your foot tapping with me, in a nice slow walking pace.

With me now: One----two----three. One----two----three. "How

small

of all that

hu

man hearts en

dure

(rest), the

part

which wars or

kings

can cause or

cure

(rest), all

hu

man things are

sub

ject to de

cay

(rest), and

when

fate summons

mon

archs must o

bey

(rest), that

time

of year thou

mayst

in me be

hold

(rest), When

yell

ow leaves or

none

or few do

hang

(rest), When

I

have fears that

I

may cease to

be

(rest), be

fore

my pen has

gleaned

my teeming

brain

(rest)." Are you with me? I feel like I'm making an exercise video.

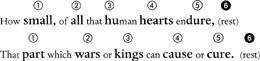

What's happening is that if you tap your foot only to the big beats, you end up with a line of inner quadruplets chugging away in sync with three large stresses. You can chart it like this: