The Anybodies (6 page)

Authors: N. E. Bode

Fern stared at the man's face. She felt a chill. He scared her. She remembered the angry glare of the man from the census bureau and his dark, ghostly hand. “The Miser.”

“That's right,” the Bone said.

Fern stared into the Miser's eyes. They were the same as the census bureau man's, weren't they? Had the Miser been the gusty dark cloud that had tried to pull her in, closer, whipping at her clothes? Was the Miser capable of turning himself from a bird to a dog with one shiver? But the bird couldn't have been him. She'd liked the bird. It had watched her kindly with its little head cocked and its eyes wet.

“You were once friends?” she asked.

“Yes. Best friends. I keep the picture as a reminder. We grew up in the circus together. The spies are a troop of little people. The Miser knew them from his ties to the circus and hired them away. My mother was a trapeze artist, as I said, and his father was the strong man. He ate nails. The Miser was once the sweet, sensitive type. He was named the Miser as a joke, because it was the opposite of who he really was. He'd write you an apology if he thought he hurt your feelings. We resorted to trickery, but I tell you, he made sure we were always the good guys.”

“But now he's after you?” Fern asked.

“He was in love with your mother, see? And she

loved me. He never got over that, I tell you. He got me put in jail as soon as I married your mother!” The Bone shook his head, sighed. “I don't want the Miser to get his hands on that book. It's powerful, and he shouldn't have it! You see, the book doesn't really mean much to either me or the Miser. It's just a big coded mess to the two of us. Only your mother could make sense of it. And he was hoping that Howard would be born with some of Eliza's powers and that he'd understand the book. I guess I was hoping too. It was clear that Howard wouldn't be able to make any more sense of it than we couldâhe lacks the gifts. But then the Miser found out that you existed, and now he wants that book again because you're the key to unlocking it.

“Honestly, Fern, and I'm not used to being honest, but I want the book because your mother loved it. I can picture her now walking down the street toward me, lost in thought, the book held tight to her chest. That big old leather book with a small leather belt wrapped around it. Your mother kept it safe, always safe.” He seemed to drift off a moment here, lost in the memory, and Fern lost herself, too. She liked this glimpse of her mother, a young woman carrying a giant book. Fern could relate to it. She loved books too, and she loved imagining that she and her mother had this in common. The Bone came to and went on. “Now we're both looking for the book. And he wants to make sure

he gets it first. Your mother would want me to have it, Fern. Me. The Miser thinks the book should be his, but he's wrong! Your mother left it for me.”

Fern wanted to see this book with her own eyes. She wanted to feel the weight of it and carry it locked to her chest. “And you don't know where it is?”

“Nope.” He shoved his hands into his pockets. “The book is for me, for you, for us, Fern. We have to find it first. The book holds more secrets. Dark secrets. He could learn how to hypnotize nations, Fern, and he wouldn't do any good with that. None.” Fern felt that sense of dread again, the windy pull of the dark cloud. The Bone looked at Fern. She knew her eyes were wide with fear. She hadn't known that there was so much at stake.

“I didn't mean to scare you!” he said.

“I'm not scared,” Fern said, but she was lying. It was too late. She was already scared.

The Bone held out his hand and Fern handed him the picture. He sighed deeply. “Your mother, she was the real thing. Before I met her, I could make people waddle around onstage or sing silly songs for the audience. But your mother taught me how to be an Anybody. I was already an okay hypnotist. But together the two of us, your mother and me, we could cure people. Together we never turned anybody into a rooster. We were healers, really. Now I try to cure folks, and that's

what happens.” He pointed to the front yard, to the rooster man. The Bone turned back to Fern. “Go ahead and eat.”

Fern wasn't sure if her hands were shaking because she was frightened or starving, or both. Mr. and Mrs. Drudger preferred oranges so dry and pruned that their white casings were brittle. Their soups were homemade and tasted like wet air. She'd never eaten an onion before, much less a raw one. Here, the orange was so juicy it dripped down to her elbows. The soup, from a can, was salty. The onion tasted like a sharp sting. She gulped whole milk, chocolate, in fact.

The Bone was up and down. He watched her eat some, gazed at the photo from time to time; but he was often drawn to the front kitchen window, where he kept an eye on the man in his yard.

“Is he still there?” Fern asked a few times, anxiously.

“Yep. Still there.”

Fern looked around the apartment. There was one neat corner with a shelf of oversized books. Fern could read the titles of the books from where she sat, things like

The Complete Book of Mathematics

. Fern assumed it was Howard's territory. That was one thing she missed here at the Bone's, her small but growing library. All of the books seemed to be Howard's. Didn't the Bone have a few of his own favorites? Fern couldn't imagine going without books. Howard's area was small

and tidy. There was a box of earplugs and an air spray, regular scent. Howard! Would he really love being with the Drudgers? Could he? Hadn't he liked something about living with the Bone after all these years? Wouldn't he miss it? Fern already felt different, and she'd only known the Bone a few hours.

When Fern finished eating, she wiped her mouth on her sleeve. It was a test. Mr. and Mrs. Drudger would have scolded her. She wanted to see what the Bone would do. He said, “You like my cooking? I once had an Anybody gig as a French chef. Those were the days!”

Fern imagined the Bone in a puffed white hat. It made her smile. She almost said, “I'm glad I'm here.” But she didn't. She was pretty sure the Bone didn't want to hear anything that might come off as soft. He'd told her that he didn't like anything mushy. Plus, she was still getting used to it all. She still felt off-kilter. She said, “I'm glad I'm not still at my house.” That was the truth. She was happy to be relieved of math camp and Lost Lake and boredom. But she was scared, too. She wanted to help get the book before the Miser did, but what if she wasn't able to? She was just a kid, after all, and not even the type to be the first one picked for kickball, or the second or the third. “What should we do about the Miser?” she asked. “How can I help?”

“Well,” said the Bone, “there's a more pressing issue.” He looked at a clock on the wall. The clock

looked unreliable, at best. It had faded numbers, and the nine had slipped down so that the clock had two sixes. The second hand was inching uphill. It got stuck, then sprang five seconds forward. “Mr. Harton.”

“Who?”

“The rooster's name is Mr. Harton. Or it was Mr. Harton before he gave up selling vacuum cleaners door-to-door to become a rooster. And, come morning, he's going to start to crow. But I've got a hunch, I've got a feeling, that you'll be able to cure him.”

“Do you think so?”

“I tried to wink at you while I was Mrs. Lilliopole. I was always trying to get you to look at me, but you never would. But then finally I did wink at you, Fern. Remember? When you were going upstairs at the Drudgers? And you winked back. Probably didn't think you were going to wink, but you did. And if an Anybody winks at another Anybody, even an Anybody who isn't really an Anybody yet, they've got to wink back. It's one of the rules from the book. And you winked, Fern. Naturally. You winked!”

DEHYPNOTIZING MR. HARTON

OH, MY OLD WRITING TEACHER, SOMETIMES I

still think of him, like now, right here at Part 2, Chapter Three, “Dehypnotizing Mr. Harton.” If he could see me now, typing feverishly, he would have to admit that I do look like a writer and act like one. I may even smell like a writer, but I'm not sure what writers smell likeâink, erasers, books? He would be astonished, I tell you, because he never had faith in me. Not one ounce! Some teachers just don't know the gem sitting right in front of them. Like you, for example, you're obviously a gem and you probably have one old stinker of a teacher who doesn't have any idea. Well, you'll show that teacher one day, you will, you will!

Like I am at this very moment in Part 2, Chapter Three. Oh, and after this there's more, more, more! In fact, I will promise right here, right now, some very freakish, bizarre behavior and outlandish surprises. Read on!

Before inviting Mr. Harton in, the Bone vacuumed. Mr. Harton had left his demonstration kit behind, and the Bone wanted to use the sample vacuum before he'd have to give it back. He didn't own a vacuum cleaner, and maybe you recall that the Bone's apartment was still very furry from the dog that'd left him for the wider, more appreciative audiences of circus life. Fern watched the Bone's harried vacuuming job. He started out on the orange sofaâFern had never seen anyone vacuum furniture before. A flurry of motion, he was nothing like Mrs. Drudger, who vacuumed in diagonal rows. The Bone vacuumed the same way he must have mowed the front yard, in ragged, starlike clusters. He'd probably borrowed the mower, too, Fern thought (and she was right). He shouted the story of Mr. Harton over the small, thrumming vacuum motor, and Fern listened intently, trying to dodge the vacuum's zipping nose.

“MR. HARTON WAS A TERRIBLE SALESMAN, FERN. HE COULDN'T SELL FAT MICE TO CATS. HE SLOUCHED. HE WAS SHIFTY-EYED. HE MUMBLED HIS DELIVERY. HE LACKED CONFIDENCE, MOST OF ALL. WITH CONFIDENCE, YOU CAN SELL ANYTHING. REMEMBER THAT,

FERN. THAT'S IMPORTANT. I LET HIM IN BECAUSE HE WAS SO PATHETIC. I TOLD HIM THAT I COULD HELP HIM WITH HIS PITCH. I COULD GET HIM THE COCKINESS HE NEEDED TO BE TOP-NOTCH. SO I HYPNOTIZED HIM. HE LEFT HERE SO FULL OF HIMSELF HE DIDN'T WANT TO SELL VACUUM CLEANERS ANYMORE. HE SAID HE WAS GOING TO SELL CONDOS OR SOMETHING. HE HAD A BROTHER WHO'D MADE A FORTUNE IN CONDOS. SO HE LEFT.”

“BUT HE'S BACK. WHAT HAPPENED?”

The Bone had strayed too far from the outlet. The plug popped from the wall. The vacuum cleaner's motor, wheezy from the intake of so much fur, wound down, its stiff lung deflated. “It's the same thing that always goes wrong these days. I'm not exactly sure how it happens. But they seem toâ¦they seem so overcome with their new personalities that they turn into some animal version of the trait I've given them. Once a stupid man turned into an owl. And a woman who wanted to have children turned into a rabbit. It doesn't always make perfect sense. Once an old man wanted to be young and he turned into a baby kangaroo.” This made Fern nervous. She didn't want to be turned into something ridiculous, and she hoped that the Bone couldn't do it accidentally. She worried about him now, the way you'd worry about someone

wandering around with a lit match who could bump into the curtains, setting the whole place on fire. “No one ever showed up at the front door to complain when your mother and I were together. No one ever showed up trying to catch flies with their tongue.” The Bone scratched his chin with his knuckles. “The process has developed some kinks.”

Fern fiddled with the key on her necklace. She thought of her diary with her mother's photograph in it. She was still not used to the idea that she had another mother, much less one she would never get to see. “Do they have to live like that for the rest of their lives?”

“Oh, no, it wears off in a couple of months or so.”

“Months!”

“But you'll be able to set Mr. Harton straight right away. I know it.”

Fern was doubtful. “I will? But I have no idea what to do.” She wanted to explain to the Bone that she wasn't very good at doing things in general. Maybe there had been some kind of mistake. I mean, so much of what the Bone had said fit in with the strange aspects of Fern's life, explaining some of the unexplainable, but this? Fern was sure she was going to disappoint the Bone, and she didn't want to. He had his hopes pinned on her.

“Don't worry. I'll walk you through it. It helps that you have the gift handed down to you. I don't want you

to be just a sideshow act. I want you to be someone who really can help people one day. But there's that other ingredient. The one I had once but don't now.” He gazed off for a moment, his eyes catching on the photograph his wife had taken of him and the Miser laughing.

In the Bone's defense (and I do defend the Bone, because although he's kind of a squirrelly guy and imperfect, he is good, deep down), hypnosis is an imprecise science. Actually, when you think of chemistry with its

H

this and its

O

that, and when you think of biology with its test tubes and beakers and its dissected worms, well, hypnosis isn't a science at all. And it isn't really an art, either, in light of the Mona Lisa and ice sculpting and baton twirling. And it isn't a sport, because you don't get points or win those statues of miniature golfers or divers glued to marble. So I'm not sure what to call it, but really it's murky territory. It's mysterious, yes, that's it. It's a mystery.

The Bone set to work. He opened the apartment door and then the main door to the house. He walked out into the yard behind Mr. Harton and flushed him inside by clapping and waving his arms. Mr. Harton was all high-step and flap. He stood in the middle of the room, his head bobbing now and then. He stared at Fern and then started to preen. He used his nose like a beak, picking at his shoulders. The Bone rolled the vacuum cleaner over

to Mr. Harton, but Mr. Harton didn't even look at it. The Bone rolled it back and forth right in front of him, but again Mr. Harton ignored it.

“That's a bad sign,” said the Bone. “He's in deep.”

With a little force, the Bone sat Mr. Harton down in a chair next to Fern at the table where she'd eaten. Her orange peel sat in the empty soup bowl with the tough heart of the onion and its crisp brown skin.

“Okay,” said the Bone, “try to get him to look at you. Try to catch and hold his stare.”

Fern stared at Mr. Harton. He had pale blue eyes that looked a little teary. They darted around the room, falling occasionally on Fern's eyes, but not staying put. Fern moved her face to block his view. She was certain that she wouldn't be able to do it. She was bound to let the Bone down, and what then? Well, terrible things could happen. Mainly, the world could come to an end. But, Fern reminded herself, she wasn't a Drudger who fibbed because of an overactive dysfunction. Her real mother never would have called her a fibber. Her real mother would have understood. Fern caught Mr. Harton's eyes, then lost them, then caught them again. Fern had to try to do this. She had to. She kept at it and, eventually, he was staring at her out of one eye, his head turned away, as if he were a bird with an eye on the side of his head. Yes, she had him!

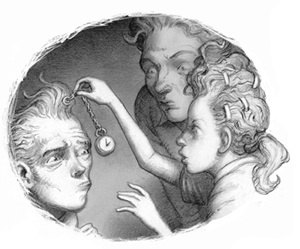

The Bone slipped Fern a pocket watch on a gold

chain. The pocket watch didn't work, of course. The Bone didn't keep track of time, as you all know by now. But the watch was shiny and, on its long chain, it swung nicely, which were the qualities the Bone looked for in a pocket watch.

“Hold it up by the chain. Make it sway back and forth and back and forth. That's right. You've got it.”

Fern was making the watch sway like a clock's ticktock, and Mr. Harton's watery eyes were hooked

on it. Fern was very proud. She smiled at the Bone, but he shook his head. “Not done yet,” he said. “More to it than that. Now don't look at the watch yourself, Fern. Don't look at it.” He began to whisper into Mr. Harton's ear, “You are getting sleepy. Very sleepy.” He kept on with this until the man's eyes blinked again and again, more slowly, until they shut and didn't open.

Fern let the watch drop to her lap.

The Bone handed her a bell, small and brass with a black wooden handle. Then he put his hands on Mr. Harton's shoulders. He said to Fern, “Say these words: âYou are not a rooster. You are a man. Return. Return. Return.' And ring this bell softly, softly each time you start to say it again. Try that.”

Fern rang it once, then started to say the words. “You are not a rooster. You are a manâ¦.” And the Bone started to hum, a deep low note. Fern felt something electric, a snappy static all around them. Each time the Bone took a breath to hum again it was like a car trying to start up. There was a

vroom vroom

of energy, something buzzing and zapping. But the engine never really revved up. She could feel the electricity rev and stall, rev and stall. But she kept on repeating it, “Return, return, return.” She was holding the bell in front of Mr. Harton's face, ringing it softly. Her arms were tired. The Bone's hum was breaking up.

Finally he said, “Okay, ring it loud now. Ring it like crazy.”

She did, and Mr. Harton startled awake with a gasp, like someone who'd been trapped underwater coming up for air.

“Stand up,” the Bone told him. He did, shakily. He glanced at the vacuum, and it was clear that he recognized it.

“Good. Good,” the Bone urged. “Walk to it.”

Mr. Harton looked at Fern and the Bone. He looked longingly at the vacuum cleaner.

“What is it?” the Bone asked. “Do you want to tell us something?”

Mr. Harton nodded and then smiled broadly. He pitched back his head and let out a loud clear yodel, a clear timeless cry of “Cockadoodledoo!” Then he put his head to his chest. His face crumpled. His eyes spilled two tears. Fern knew there had been something, some kind of magic charge, and although it wasn't enough, she knew she'd felt it and it was undeniable. She wondered if spies were listening to all of this, if the Miser would hear about this sad failure.

The Bone sighed, and Mr. Harton half-heartedly stepped to the vacuum cleaner, grabbed its handle, and rolled it toward the door. The Bone opened the first door for him, then the second. Mr. Harton, still a rooster man, bobbed his head, but Fern couldn't tell if

it was an acknowledgment or simply a rooster like flinch. Fern and the Bone followed him outside and watched him strut down the street with his vacuum cleaner bumping and rolling behind him.