The Anybodies (7 page)

Authors: N. E. Bode

SPIES

THAT NIGHT, THE BONE THREW SHEETS ON A ROW

of saggy beanbag chairsâa bed for himselfâand sheets on the orange, now less furry, sofa for Fern. They lay down across the room from each other in the dark. Except for the occasional roar of a passing train, the apartment was quiet. There was a little slice of moonlight coming in through a crack in the curtains. Fern was writing in her diary as silently as she could. She had a lot to catch up on. She wrote about Milton Beige, Howard, the Bone, and Mary Curtainâthe real Mary Curtain in her kitchen somewhereâand Marty, the fake Mary Curtain. She wrote about the rooster man and the raw onion and the orange and the Miser and

her mother, most of all her mother. She pulled the picture out, gazed at it, and then wrote:

When I look at the picture of her, I mean really look, really stare right into her eyes, I feel like I know her. Sometimes I feel like we are thinking the same thing or feeling the same thing, like our hearts miss each other.

The Bone started to hum a sad love song, and then he sang a few of the words, “Sweet, sweet, my sweet darling angel, where have you gone, where have you gone?”

The song made Fern want to cry. She put the picture back into the diary and closed it. She stared up at the ceiling, and a lump rose in her throat. When she coughed, hoping to clear it, the Bone stopped singing. He coughed too, as if embarrassed he'd been caught. Fern thought that maybe he'd thought she was asleep.

“Soon the Bartons will start clog dancing upstairs,” the Bone said.

“At least the rooster won't wake us up,” Fern said.

“True.”

The Bone let out an exhausted sigh. He said, “Your mother knew she wasn't going to make it. She just knew. She told me over the jail phone, looking at me through the Plexiglas. I told her she was silly. She started giving me information about the book, where she'd leave it for me, a special spot, but I hushed her up. I said I didn't want to hear about it. She gave up talking about it. She gave up pretty easily, in fact. She didn't want to upset

me. Or, sometimes I think, maybe⦔

“What?” Fern asked, propping herself up on her elbows.

“Maybe she was hatching a bigger plan. Your mother was tricky. She always had a way of getting what she wanted.”

“What did she want when she was alive?” Fern asked, now sitting up and staring at the Bone through the weak light.

“Oh, I don't know.”

“Really,” Fern said, “tell me.”

The Bone thought out loud, “What did she want? What did she really want? She wanted for me and the Miser to be friends again. And I guess she'd have loved it if I'd gotten along with her motherâ¦.”

Fern hadn't thought about this before. She had a grandmother. This took her by surprise. She wanted to meet her grandmother now. She had to!

The Bone went on, “But her mother is a loon, I tell you. C-R-A-Z-Y. She runs a boarding house but truly lives in a world of books. And I mean that very seriously. I never got along with the old womanâ¦.”

Fern stopped listening now. She was starting to understand somethingâher mother was a plotter. She had a plan. She was smart. She wanted the Bone and the Miser to be friends again. Fern guessed that her mother felt responsible for the two cutting ties, for coming between

them, maybe. And she wanted the Bone to become close to her mother. Well, of course, she loved these two people.

Now that Fern knew what her mother wanted, she had to think of how her mother would use the book to get it. Her mother knew the futureâthat she was going to dieâbut how far into the future could she see? Did her mother know that one day Fern would be here trying to piece it all together? Fern was on her feet now, pacing. It helped her think.

“What is it?” the Bone asked.

Fern didn't answer because she hadn't really heard him. She was thinking of her mother's heart and her own, her mother's mind and her own. How would Fern's mother use the book to bring all of these people togetherâthe Miser, the Bone, Fern's grandmother, and maybe even Fern herself? Wasn't she part of the puzzle? Did this plan of her mother's rely on Fern? Fern paced some more. One thought turned to the next and the next and finally she knew where the book would turn up. There was only one logical spot. The one place that Fern was most drawn to, the one place where they would all wind up. “Well, that's it then,” Fern said.

“That's what?” the Bone asked.

“The book is at her mother's house!” Fern said loudly.

“What? You're joking.”

“No.” And now she jogged over to the windows and yelled it. “The book is at Eliza's mother's house!” She yelled it again, just because she liked being allowed to yell. “THE BOOK IS AT ELIZA'S MOTHER'S HOUSE!!”

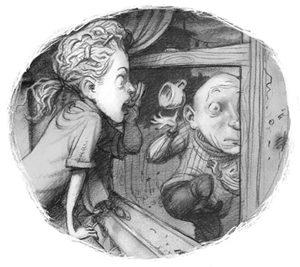

She pulled the curtain back quickly and there, on the other side of the window, was a tiny pale face with a sharp nose. It was a small, little, tiny man with a cup held to the window, pressed to his ear. The ear was big

compared to the man's small head. Too big. He stared at Fern for a split second and then took off, running down the train tracks to a red van with gold lettering, too far away to read, a few other small men straggling after him.

“Spies!” Fern said. “And they heard it all!” She was triumphant.

She let the curtain drop and turned to the Bone, who was now standing up, his spine straight, his expression electrified. “Why did you let them hear it? Why didn't you scare them off first?”

“Simple,” Fern said. “How could you become friends with the Miser again if he doesn't know the book is at her mother's? And how could you become close to my grandmother if the book isn't there? And how would I eventually know my grandmother at all if it isn't there? We've all got to be there together.”

You see, Fern is quite smart. She isn't good at math camp, but she's bright, quick-witted. She'd never known that she was right before. She'd never had that strong conviction. But now she did, and she felt something else that was new: stubbornness. Now that Fern knew she was right, there was no changing her mind. Stubbornness is very bad in someone who has only bad ideas, but it's very good in someone who has good ideas. Luckily Fern is the smart kind of stubborn. And it can't be denied that Fern liked this plan especially

because it would bring her to her grandmother, and Fern hadn't given up on the idea of finding a place that felt like home. Maybe she would find it there, Fern thought, in the house where her mother had grown up with the woman who'd raised her.

The Bone paced back and forth. “No, no. Eliza wouldn't leave the book with her mother. She wouldn't do that to me. Her mother can't stand me! And now the Miser, too! It's all wrong. All very, very wrong. I won't go. I won't do it!”

But Fern knew she was right. She knew she was very, very right. She looked at the Bone with her big eyes and she smiled. He sagged. And just then, from above, an accordion started upâhappy, bouncy musicâand the clogs set in like a hailstormâhailstones the size of clogs. The Bone stared up at the ceiling then back at Fern, and Fern knew that the Bone knew the only other option was to stay where they were. She knew she'd won.

THE HOUSE OF BOOKS

THE NOSE

THE BONE WAS DRIVING THE OLD JALOPY. FERN

sat next to his suitcase and her own bag in the backseat where the seat belt worked. The Bone was giving instructions about the new identities he'd created for himself and Fern, but it was hard to concentrate on what he was saying because he'd turned himself into an encyclopedia salesman. He was wearing a name tag pinned to the lapel of a shabby green suit:

HELLO

!

MY NAME IS

:

MR

.

BIBB

,

SALES ASSOCIATE

. His hair, which had been a graying blond puff, was flat, black, and looked shellacked, shiny as a Christmas ornament. Fern had pretended to be asleep in the morning while she listened to him humming in the low baritone he'd used with Mr.

Harton. She heard him curse under his breath, and then he cheered, “Yes, yes, that's it!” Shortly thereafter, the house smelled of something sharp like paint. The smell reminded Fern of Mr. Drudger daubing and rubbing shoe polish into his loafers. Fern guessed that the Bone had tried to become a different person through the magical transformations based on

The Art of Being Anybody

. He'd failed, and resorted to faking it. Had he put shoe polish on his hair? Was that new bulbous nose made of rubber and glued on? And that smarmy little mustache?

The sloppy old car made Fern feel seasick, a queasiness that was aggravated by the watery sound of the Bone's new lisp, a Mr. Bibb trait he'd taken on. There were too many

s

's in everything. “I'm Missster Bibb and you're Ida Bibb, my daughter. And we're jusst passssing through for a few weekss. We need a room for jussst that much time. We're heading wesst to visssit family. Jusst let me do the talking.”

When Fern came up with the plan to look for the book at her grandmother's, she hadn't realized that she and the Bone couldn't show up as themselves on her doorstep. No, no, the Bone had convinced her that they'd each have to go as somebody else. This was disappointing because Fern had wanted to go to her grandmother's house to figure out if it felt like home. How could she do this if she was Ida Bibb? “But I sometimes

blurt out weird things when I'm nervous,” Fern said. “I do sometimes. My brain just rattles on like a train with too many cars, and then I find out I've just said something that doesn't make sense. What can I do about it? I can't do much. Can I?” It dawned on Fern that she wasn't saying all of this in her head. She was saying it out loud and that was a nice thing. Still she was nervous, and she pulled three barrettes from her pocket to lock down her wild hair.

“Think of milk. Think of a big glasss of milk. Sstop talking and try to conjure the biggesst, whitesst, creamiesst glasss of milk you can, all beaded with dropss of water. Try to make it clear in your head, like you could jusst reach into spacse and pick it up and drink it. Think of ssoup, cheesse, lemonss, appless, plumss. That'll keep your brain occupied.”

“Do you have to talk like that?” Fern felt nauseous and thinking about milk, soup, cheese, lemons, apples, and plums wasn't helping matters.

“Yesss.”

“I don't think she'll believe us! I don't think this'll work,” Fern said. “You should ask her for the book. Maybe she knows she has it and will just hand it to you.”

“Nothing further from the truth. That woman doessn't like me. She never did. Your mother told her that she'd reformed me, turned me into a real healer.

A good guy. But her mother wouldn't have much to do with me. âHe doessn't even like to read!' her mother would ssay, like that wass the greatesst sssin in the world. The only good thing isss that she didn't like the Missser either. She didn't like either of uss.”

“Do you like to read?”

“I liked when your mother read to me. She read like a dream.”

“I just have a feeling it's going to be strange,” Fern said.

“It will.”

“I've got a bad feeling.”

“Today'ss a good day, Fern! It'ss a very good day. Thingss are already looking up.”

“They are?”

He pulled the car over onto a grassy shoulder and stopped. Fern looked at the Bone. He said, “Look!

Look at my nosse.”

“What?”

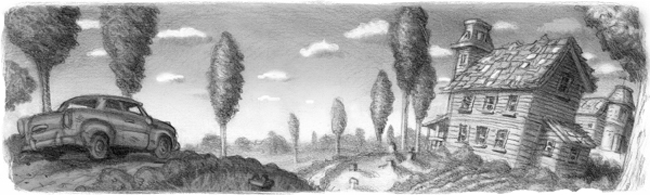

He pushed the squat nose, then pulled on it, then wiggled it around. It looked fat, real, completely attached. “That there iss the real McCoy, Fern, I tell you. I couldn't get any of the other sstuff right, but the nosse, that iss a genuine nossse, fully transsformed. I may be faking Mr. Bibb, but my nosse issn't. It'ss the firsst time in a long time that I ever got any of it right. I wass thinking of the Great Realdo. He'd helped me oncse before, when I wass wooing your mother. I wass thinking today the ssame way I wass thinking all those yearss ago: âI need your help. Jusst an inch of your great sspirit. Help me, Great Realdo.' And it worked.” He smiled. He reached behind and patted Fern on the head. It was a soft little pat, not a mushy pat, but it was just a little sweet. He sighed and looked out the front windshield. “There'ss the housse.” He pointed

down a long dirt driveway to a tall yellow farmhouse and a large red barn surrounded by fields. There was a sign dug into the dirt:

BOARDERS WELCOME. MUST BE TIDY AND WELL-READ

.

The Bone gazed up at the house. He started humming the song Fern had heard him singing the night before. “Sweet, sweet, my sweet darling angel, where have you gone, where have you gone?” He put the car in gear and headed down the long, bumpy driveway.

Fern stuck her head out the window. She stared at the house. She figured it looked like a place she could call home; it was hard to tell, really, when she didn't know exactly what a place she could call home should look like. A wind kicked up, gusted. One of the shingles on the roof lifted in the breeze but didn't come off. Something white fluttered under the shingle, just for a moment, a quick flipping of what seemed like pages. Was the roof made of books? The Bone jerked the car to a stop in front of the house. Dust rose up, then settled. No, no, it was just an ordinary house, Fern assured herself, with an ordinary roof.