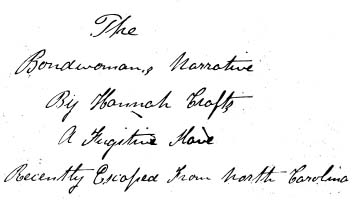

The Bondwoman's Narrative (11 page)

23.

Letter from Tom Parramore to Henry Louis Gates, Jr., November 16, 2001.

24.

Bryan Sinche pointed this out to me.

25.

See

The Case of Passmore Williamson

(Philadelphia: Pennsylvania Anti-Slavery Society, 1855), and Still, pp. 86–97. Two versions of Jane Johnson’s testimony appear

in Appendix B. See Still, pp. 94–95.

26.

David Brion Davis, “The Enduring Legacy of the South’s Civil War Victory,”

New York Times,

August 26, 2001, section 4, p. 6.

27.

Conversation with Tim Bingaman, Mormon Family History Library, May 15, 2001.

28.

Giles R. Wright,

Afro-Americans in New Jersey

(Trenton: New Jersey Historical Commission, 1988), p. 39.

29.

This book is reprinted in

The Black Biographical Dictionary Index,

ed. by Randall and Nancy Burkett and Henry Louis Gates, Jr. (Alexandria, Va.: Chadwyck Healy, 1985).

30.

Elizabeth M. Perinchiet,

History of the Cemeteries in Burlington County, New Jersey, 1687–1975

(n.p. 1978), p. 30.

31.

Letter from Nina Baym to Henry Louis Gates, Jr., May 9, 2001.

32.

Letter to Henry Louis Gates, Jr., October 26, 2001.

33.

Letter to Henry Louis Gates, Jr., November 2, 2001.

A Note on Punctuation and Spelling

Throughout the text, every effort was made to print the novel as it appeared in the original holograph. Hannah Crafts’s spelling

has been retained, though, on occasion, a bracketed insertion has been added to aid readability (e.g., “to[o]”); the use of

[sic] has been restricted to syntactical matters.

Periods at the end of sentences have been inserted globally; question marks after interrogatory sentences appear only where

Hannah Crafts put them; crossed-out words indicate Crafts’s own revisions. Bracketed quotation marks have been added around

dialogue where their absence would impede the readability of the narrative.

In presenting this record of plain unvarnished facts to a generous public I feel a certain degree of diffidence and self-distrust.

I ask myself for the hundredth time How will such a literary venture, coming from a sphere so humble be received? Have I succeeded

in portraying any of the peculiar features of that institution whose curse rests over the fairest land the sun shines upon?

Have I succeeded in showing how it blights the happiness of the white as well as the black race? Being the truth it makes

no pretensions to romance, and relating events as they occurred it has no especial reference to a moral, but to those who

regard truth as stranger than fiction it can be no less interesting on the former account, while others of pious and discerning

minds can scarcely fail to recognise the hand of Providence in giving to the righteous the reward of their works, and to the

wicked the fruit of their doings.

In Childhood

Look not upon me because I am black; because the sun hath looked upon me.

S

ONG OF

S

OLOMON

It may be that I assume to[o] much responsibility in attempting to write these pages. The world will probably say so, and

I am aware of my deficiencies. I am neither clever, nor learned, nor talented. When a child they used to scold and find fault

with me because they said I was dull and stupid. Perhaps under other circumstances and with more encouragement I might have

appeared better; for I was shy and reserved and scarce dared open my lips to any one I had none of that quickness and animation

which are so much admired in children, but rather a silent unobtrusive way of observing things and events, and wishing to

understand them better than I could.

I was not brought up by any body in particular that I know of. I had no training, no cultivation. The birds of the air, or

beasts of the feild are not freer from moral culture than I was. No one seemed to care for me till I was able to work, and

then it was Hannah do this and Hannah do that, but I never complained as I found a sort of pleasure and something to divert

my thoughts in employment. Of my relatives I knew nothing. No one ever spoke of my father or mother, but I soon learned what

a curse was attached

to my race, soon learned that the African blood in my veins would forever exclude me from the higher

walks of life. That toil unremitted unpaid toil must be my lot and portion, without even the hope or expectation of any thing

better. This seemed the harder to be borne, because my complexion was almost white, and the obnoxious descent could not be

readily traced, though it gave a rotundity to my person, a wave and curl to my hair, and perhaps led me to fancy pictorial

illustrations and flaming colors.

The busiest life has its leisure moments; it was so with mine. I had from the first an instinctive desire for knowledge and

the means of mental improvement. Though neglected and a slave, I felt the immortal longings in me. In the absence of books

and teachers and schools I determined to learn if not in a regular, approved, and scientific way. I was aware that this plan

would meet with opposition, perhaps with punishment. My master never permitted his slaves to be taught. Education in his view

tended to enlarge and expand their ideas; made them less subservient to their superiors, and besides that its blessings were

destined to be conferred exclusively on the higher and nobler race. Indeed though he was generally easy and good-tempered,

there was nothing liberal or democratic in his nature. Slaves were slaves to him, and nothing more. Practically he regarded

them not as men and women, but in the same light as horses or other domestic animals. He

furnished

supplied their necessities of food and clothing from

the same

motives of policy, but [di]scounted the ideas of equality and fraternity as preposterous and absurd. Of course I had nothing

to expect from him, yet “where there’s a will there’s a way.”

I was employed about the house, consequently my labors were much easier than those of the field servants, and I enjoyed intervals

of repose and rest unknown to them. Then, too, I was a mere child and some hours of each day were allotted to play. On such

occasions, and while the other children of the house were amusing

themselves I would quietly steal away from their company

to ponder over the pages of some old book or newspaper that chance had thrown in [my] way. Though I knew not the meaning of

a single letter, and had not the means of finding out I loved to look at them and think that some day I should probably understand

them all.

My dream was destined to be realized. One day while

I was

sitting on a little bank, beneath the shade of some large trees, at a short distance from my playmates,

when

an aged woman approached me. She was white, and looked venerable with her grey hair smoothly put back beneath a plain sun

bonnet, and I recollected having seen her once or twice at my master’s house whither she came to sell salves and ointments,

and hearing it remarked that she was the wife of a sand-digger and very poor.

She smiled benevolently and inquired why I concealed my book, and with child-like artlessness I told her all. How earnestly

I desired knowledge, how our Master interdicted it, and how I was trying to teach myself. She stood for a few moments apparently

buried in deep thought, but I interpreted her looks and actions favorably, and an idea struck me that perhaps she could read,

and would become my teacher. She seemed to understand my wish before I expressed it.

“Child” she said “I was thinking of our Saviour’s words to Peter where he commands the latter to ‘feed his lambs.’ I will

dispense to you such knowledge as I possess. Come to me each day. I will teach you to read in the hope and trust that you

will thereby be made better in this world and that to come.[”] Her demeanor like her words was very grave and solemn.

“Where do you live?[”] I inquired.

“In the little cottage just around the foot of the hill” she replied.

“I will come: Oh how eagerly, how joyfully” I answered “but if

master finds it out his anger will be terrible; and then I

have no means of paying you.”

She smiled quietly, bade me fear nothing, and went her way. I returned home that evening with a light heart. Pleased, delighted,

overwhelmed with my good fortune in prospective I felt like a being to whom a new world with all its mysteries and marvels

was opening, and could scarcely repress my tears of joy and thankfulness. It sometimes seems that we require sympathy more

in joy than sorrow; for the heart exultant, and overflowing with good nature longs to impart a portion of its happiness. Especial[l]y

is this the case with children. How it augments the importance of any little success to them that some one probably a mother

will receive the intelligence with a show of delight and interest. But I had no mother, no friend.

The next day and the next I went out to gather blackberries, and took advantage of the fine opportunity to visit my worthy

instructress and receive my first lesson. I was surprised at the smallness yet perfect neatness of her dwelling, at the quiet

and orderly repose that reigned

in

through all its appointments; it was in such pleasing contrast to our great house with

its bustle, confusion, and troops of servants of all ages and colors.

“Hannah, my dear, you are welcome” she said coming forward and extending her hand. “I rejoice to see you. I am, or rather

was a northern woman, and consequently have no prejudices against your birth, or race, or condition, indeed I feel a warmer

interest in your welfare than I should were you the daughter of a queen.[”] I should have thanked her for so much kindness,

and

interest

such expressions of motherly interest, but could find no words, and so sat silent and embarrassed.

I had heard of the North where the people were all free, and where the colored race had so many and such true friends, and

was

more delighted with her, and with the idea that I had found some of them than I could possibly have expressed in words.

At length while I was stumbling over the alphabet and trying to impress the different forms of the letters on my mind, an

old man with a cane and silvered hair walked in, and coming close to me inquired “Is this the girl

mother

of whom you spoke, mother?” and when she answered in the affirmative he said many words of kindness and encouragement to

me, and that though a slave I must be good and trust in God.

They were an aged couple, who for more than fifty years had occupied the same home, and who had shared together all the vicissitudes

of life—its joys and sorrows, its hopes and fears. Wealth had been theirs, with all the appliances of luxury, and they became

poor through a series of misfortunes. Yet as they had borne riches with virtuous moderation they conformed to poverty with

subdued content, and readily exchanged the splendid mansion for the lowly cottage, and the merchant’s desk and counting room

for the fields of toil. Not that they were insensible to the benefits or advantages of riches, but they felt that life had

something more— that the peace of God and their own consciences united to honor and intelligence were in themselves a fortune

which the world neither gave nor could take away.

They had long before relinquished all selfish projects and ambitious aims. To be upright and honest, to incumber neither public

nor private charity, and to contribute something to the happiness of others seemed to be the sum total of their present desires.

Uncle Siah, as I learned to call him, had long been unable to work, except at some of the lighter branches of employment,

or in cultivating the small garden which furnished their supply of exce[l]lent vegetables and likewise the simple herbs which

imparted such healing properties to the salves and unguents that the kind old woman distributed around the neighborhood.

Educated at the north they both felt keenly on the subject of slavery and the degradation and ignorance it imposes on one

portion of the human race. Yet all their conversation on this point was tempered with the utmost discretion and judgement,

and though they could not be reconciled to the system they were disposed to stand still and wait in faith and hope for the

salvation of the Lord.

In their morning and evening sacrifice of worship the poor slave was always remembered, and even their devout songs of praise

were imbued with the same spirit. They loved to think and to speak of all mankind as brothers, the children of one great parent,

and all bound to the same eternity.

Simple and retiring in their habits modest unostentatious and poor their virtues were almost wholly unknown. In that wearied

and bent old man, who frequently went out in pleasant weather to sell baskets at the doors of the rich few recognised the

possessor of sterling worth, and the candidate for immortality, yet his meek gentle smile, and loving words excited their

sympathies and won their regard.