The Cerebellum: Brain for an Implicit Self (39 page)

Read The Cerebellum: Brain for an Implicit Self Online

Authors: Masao Ito

Tags: #Science, #Life Sciences, #Medical, #Biology, #Neurology, #Neuroscience

A structure for the thought system may consist of several so-far-proposed neural systems. For example, the working memory system maintains and stores information in the short term. Its core component is the supervisory activating system that is an attentionally limited controller (

Norman and Schallice, 1986

). This core forms the central executive of the working memory system that is located in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (

Smith and Jonides, 1997

;

Stuss and Knight, 2002

;

Baddeley, 2003

).

It has been proposed that when a stimulus is presented in the realm of thoughts and ideas, it is maintained in the working memory, where it is compared with mental models stored in the temporoparietal cortex. Comparison is also made to cerebellar internal models, which have been copied from mental models and stored in the cerebellum. If a received stimulus matches a mental model or an internal model, the stimulus is considered at the level of conscious awareness to be familiar and the thought process is completed. If the stimulus is truly novel, however, existing models will not recognize the stimulus. Error signals are then generated that (1) suppress at the level of conscious awareness acceptance of the idea that the mental model is familiar, (2) activate the attentional system, which in turn

activates the working memory system, which will then strengthen the search for stored mental and internal models, and (3) modify internal models in the cerebellum if errors continue to occur. Eventually, the stimulus will find a matching counterpart in the pools of mental models and internal models. Then the suppression imposed in the first step will be removed in a manner analogous to the Schmajuk-Lam-Gray (SLG) model that simulated the mechanism of classic conditioning (

Schmajuk et al., 1996

). The final process is an “aha” at the level of conscious awareness; that is, expression of the fact that a successful conversion has taken place. In other words, the original stimulus is no longer novel. The preceding processes and mechanisms may well be the basis for creativity and innovation (

Ito, 2007

;

Vandervert et al., 2007

).

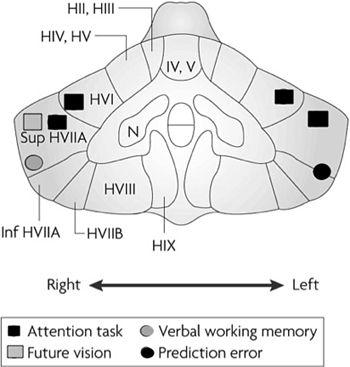

Numerous studies have now shown cognitive activity in the cerebellum. For example, in an fMRI study, when the subject unexpectedly received painful heat stimulation, the hippocampus, superior frontal gyrus, superior parietal gyrus, and an extreme part of lateral part of the cerebellum were activated conjointly (

Ploghaus et al., 2000

) (

Figure 54

, prediction error). This observation is consistent with previous considerations about explicit and implicit thought. In another fMRI study, subjects pressed a button at a comfortable self-determined pace versus during an attention task, which tested the ability to selectively attend and respond to a variety of visual targets. The cerebellum exhibited significant activation during the attention versus self-generated tasks (

Allen and Courchesne, 2003

) (Figure 59, attention).

Figure 54. Mental activities in the cerebellum.

Neuroimaging studies have provided evidence of a role for the cerebellum in various mental activities. The figure shows a coronal section of a human cerebellum, on which circles indicate the sites of observed neuronal activity. The tasks that elicited these activities include those for attention, future vision, and verbal working memory. Activity observed when a subject received an unexpected painful heat stimulus on the back of the left hand is also indicated as responses to a prediction error. Abbreviations: A–B, subdivisions of hemispheric areas; H II–VIII, areas of the cerebellar hemispheres; Inf, inferior; Sup, superior. (From

Ito, 2008

.)

The activation of a thought system as postulated above seems also to occur in various language tasks. Neuroimaging and lesion studies in humans suggest that the right posterolateral cerebellar hemisphere is involved in certain aspects of language performance. In a task that required changing nouns into verbs, learning was impaired by a large cerebellar infarction (

Fiez et al., 1992

). In normal subjects, this task co-activated the left prefrontal cortex and the left parietal cortex together with the right posterolateral portion of the cerebellum (

Fiez et al., 1996

). A similar co-activation of the left prefrontal cortex, left dorsolateral cortex, and right cerebellum was induced during silent performance of a verbal fluency task. The subjects were instructed to think silently about as many words that they knew to begin with a specified letter (

Schlosser et al., 1998

). In another study, the tasks used included antonym generation, noun (category member) generation, verb selection, and a lexical decision. The subjects compared were a normal (control) group and groups

with focal right- or left-side posterolateral cerebellar lesions. The results showed that the subjects with a right cerebellar lesion were impaired only in their performance of the antonym generation task. The deficit was not due solely to deficits in “mental movement” coupled with a verb. Rather, the faulty internal generation of a word seemed to be a key factor for eliciting the deficit (

Gebhart et al., 2002

).

The Wisconsin card-sorting test has been used to examine functions of the prefrontal cortex. Participants were given cards that could be sorted by color, shape, or name, and their mental task was to deduce the correct sorting criterion. After several consecutive correct responses, the correct sorting criterion was changed without warning. PET imaging revealed that the test co-activated the left (or bilateral) dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, bilateral inferior parietal cortex, left superior occipital gyrus, and the left neocerebellum (

Nagahama et al., 1996

).

In testing verbal working memory, participants were asked to remember six letters or one letter presented visually. These letters were presented visually only once to the subjects for 1.5 seconds. After a 5-second delay, one lowercase consonant letter was presented as a probe stimulus. For the high-load condition, this probe matched one of the six letters in the array for half of the trials. For the low-load condition, the probe matched the single letter in parentheses in half of the trials. One trial, 8.0 seconds in duration, was repeated four times in each block, and 12 such blocks were presented for 6.4 minutes. The high-load test, but not the low-load one, increased fMRI activity in certain regions of the bilateral superior cerebellar hemispheres (left superior HVIIA and right HVI), the right cerebellar hemisphere (HVIIB), and portions of the posterior vermis (VI and superior VIIA) (

Desmond et al., 1997

) (

Figure 54

). In another study, one task required producing as many words as possible (excluding proper names), beginning with a specific letter such as

F

,

A

, and

S

(letter task), and another task required producing as many different words as possible belonging to the semantic categories for “birds” and “furniture” (semantic task). A 60-second period was granted for each letter and semantic task. It was found that cerebellar patients were deficient in their phonemic rule performance but quite capable in semantic rule performance (

Leggio et al., 2000

).

Another interesting observation was an fMRI study in which the left lateral premotor cortex, left precuneus (part of the superior parietal lobule hidden in the medial longitudinal fissure), and right posterior cerebellum were shown to be more active while envisioning the future than while recollecting the past (

Figure 54

). These regions were similar to those that became more active while imagining (simulating) bodily movements. Another set of brain regions including the bilateral posterior cingulate, bilateral parahippocampal gyrus, and left occipital cortex displayed similar activity during both future and past mentation tasks. This similarity was attributed to the reactivation of previously experienced visual-spatial contexts into which the subjects placed their future scenarios (

Szpunar et al., 2007

).

Chess players require the capability to predict what occurs consequent to a lengthy alternating series of moves made by them and their opponents. Neuroimaging studies of novice chess players revealed bilateral activation in the premotor area, parietal cortex, and occipital lobe, and unilateral activation in the left cerebellar hemisphere (

Atherton et al., 2003

). Similar results were reported for the Chinese board game “Go” (

Chen et al., 2003

). Quite recently, we compared neuroimaging data for two groups of Japanese chess (Shogi) players: one group of well-trained professional players and the other less-well-trained amateur players (

Fujii et al., 2009

). We imposed quick checkmate tasks on these players. They were instructed to pay attention to a chess board showing a stage of a game, and

their task was to determine whether a checkmate could or could not be made. The number of correct answers was high (near 100%) for professional players and much lower (~50%) for amateur players. fMRI activity during these tasks are now under study.

The cognitive sequela that follows damage to the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex is similar to that following damage of the neocerebellum (

Diamond, 2000

). A patient with paraneoplastic cerebellar degeneration was shown to exhibit selective frontal-executive disturbance, psychomotor slowing, and affective change, despite the finding that there was no apparent extracerebellar involvement (

Collinson et al., 2006

). These findings underline the importance of the cerebellum in regulating cognitive function.

Cerebellar mutism is another indication of the cerebellum’s role in language acquisition and performance. This syndrome typically affects children and, in rare cases, young adults. They become mute one to two days after the surgical removal of a tumor in the posterior cranial fossa. The surgery requires a certain degree of damage to the cerebellar hemispheres. The syndrome, which persists for one to four months, is not accompanied by disturbances of consciousness and language comprehension. It has been suggested that the obligatory damage to the cerebellar hemispheres is the most important factor in development of the mutism (

Janssen et al., 1998

).

In a variety of brain diseases that cause mental disorders, patients often display motor disorders caused by cerebellar dysfunction. This occurs when pathological changes occur in cerebellar areas devoted to movement and other areas implicated in mental activities. One study showed that over 90% of autistic patients examined at autopsy had well-defined anatomical abnormalities in the cerebellum (

Carper and Courchesne, 2000

). Other studies on autism showed that the size of Purkinje cells was reduced in these subjects (

Fatami et al., 2002

) and nicotinic receptor abnormalities have also been observed (

Lee et al., 2002

). A genetic deficit in autism has been found (Sadakata et al., 2007a,b) and hyperserotonemia was recognized in autistic individuals and their relatives (

Lee et al., 2002

). Allen and Courchesne (

2003

) examined fMRI activation within anatomically defined cerebellar regions in autistic patients versus matched control healthy subjects. For a motor task, subjects pressed a button at a comfortable pace, and CNS activation was compared to the rest condition. For an attention task, visual stimuli were presented one at a time on a screen, and subjects pressed a button each time a target appeared. Activation was again compared to the visual rest condition. While performing these

tasks, autistic individuals showed significantly greater cerebellar motor activation and significantly less cerebellar attention activation. Autistic patients are characterized by the defective “Theory of Mind,” that is, loss of the ability to understand the thoughts and motivational processes of other individuals, with consequent actions that are socially aberrant (

Deuel, 2002

). This deficit may involve an autistic subject’s inability to guess what another person believes or desires because the subject cannot simulate an internal model of the other person. Defective central coherence is manifested as an inability to mold diverse and detailed internal information into relevant higher-order concepts that guide behavior over the long term. This again may reflect the inability of forming an internal model that embodies high-order concepts.

Developmental dyslexia is a syndrome that includes difficulty in separating words into discrete segments (such as phonemes). In turn, this leads to difficulty in learning spelling-sound correspondences. It has been suggested that the underlying deficit is the inability of the brain to filter irrelevant data such as perceptual noise (

Sperling et al., 2005

). The focus of this dysfunction has been placed in the frontal lobe and the temporal lobe (

Galaburda et al., 1985

), a magnocellular component of the visual pathway (

Stein and Walsh, 1997

), and the cerebellum (

Nicolson et al., 2002

). The cerebellar theory of dyslexia originated from the observation that dyslexic children perform less well than control children in certain motor (including balancing) tasks. One study showed that when the speed and accuracy of pointing were combined, dyslexic participants performed less effectively than control subjects. Furthermore, there was a significant relationship between performance of the pointing task and literacy skills: that is, a regression analysis showed that the error and speed of pointing contributed significantly to the variance in literacy skill (

Stoodley et al., 2006

).