The Charlemagne Pursuit (46 page)

“That came from the Ahnenerbe records I obtained,” Dorothea said. “I remember. I looked at it in Munich.”

“Mother retrieved them,” Christl said, “and noticed this photograph. Look on the floor—the symbol is clearly visible. This was published in the spring of 1939, an article Grandfather wrote about the previous year’s expedition.”

“I told her those records were worthwhile,” Dorothea said.

Malone faced Taperell. “Seems that’s where we’re going.”

Taperell pointed to the map. “This area here, on the coast, is all ice shelf with seawater beneath. It extends inland about five miles in what would be a respectable bay, if not frozen. The cabin is on the other side of a ridge, maybe a mile inland on what would be the bay’s west shore. We can drop you there and pick you back up when you’re ready. Like I said, reckon you’re in luck with the weather, it’s a scorcher out there today.”

Minus thirteen degrees Celsius wasn’t his idea of tropical, but he got the point. “We’ll need emergency gear, just in case.”

“Already have two sleds prepared. We were expecting you.”

“You don’t ask a lot of questions, do you?” Malone quizzed.

Taperell shook his head. “No, mate. I’m just here to do my job.”

“Then let’s eat that tucker and get going.”

EIGHTY-FOUR

FORT LEE

“M

R. PRESIDENT,” DAVIS SAID.

“W

OULD IT BE POSSIBLE FOR YOU TO

simply explain yourself. No stories, no riddles. It’s awfully late, and I don’t have the energy to be patient

and

respectful.”

“Edwin, I like you. Most of the assholes I deal with tell me either what they think I want to hear or what I don’t need to know. You’re different. You tell me what I have to hear. No sugarcoating, just straight up. That’s why when you told me about Ramsey, I listened. Anybody else, I would have let it go in one ear and out the other. But not you. Yes, I was skeptical, but you were right.”

“What have you done?” Davis asked.

She’d sensed something, too, in the president’s tone.

“I simply gave him what he wanted. The appointment. Nothing rocks a man to sleep better than success. I should know—it’s been used on me many times.” Daniels’ gaze drifted to the refrigerated compartment. “It’s what’s in there that fascinates me. A record of a people we’ve never known. They lived a long time ago. Did things. Thought things. Yet we had no idea they existed.”

Daniels reached into his pocket and removed a piece of paper. “Look at this.”

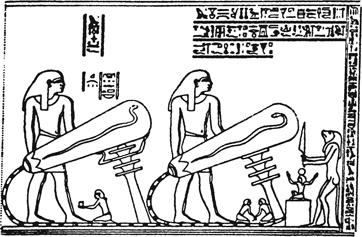

“It’s a petroglyph from the Hathor Temple at Dendera. I saw it a few years ago. The thing’s huge, with towering columns. It’s fairly recent, as far as Egypt goes, first century before Christ. Those attendants are holding what looks like some kind of lamp, supported on pillars, so they must be heavy, connected to a box on the ground by a cable. Look at the top of the columns, beneath the two bulbs. Looks like a condenser, doesn’t it?”

“I had no idea you were so interested in things like this,” she said.

“I know. Us poor, dumb country boys can’t appreciate anything.”

“I didn’t mean it that way. It’s just that—”

“Don’t sweat it, Stephanie. I keep this to myself. But I love it. All those tombs found in Egypt, and inside the pyramids—not a single chamber has smoke damage. How in the crap did they get light down into those places to work? Fire was all they had, and lamps burned smoky oil.” He pointed at the drawing. “Maybe they had something else. There’s an inscription found at the Hathor Temple that says it all. I wrote it down.” He turned the drawing over. “

The temple was built according to a plan written in ancient writing upon a goatskin scroll from the time of the Companions of Horus.

Can you imagine? They’re saying right there that they had help from a long time ago.”

“You can’t really believe Egyptians had electric lights,” Davis said.

“I don’t know what to believe. And who said they were electric? They could have been chemical. The military has tritium gas-phosphor lamps that shine for years without electricity. I don’t know what to believe. All I know is that petroglyph is real.”

Yes, it was.

“Look at it this way,” the president said. “There was a time when the so-called experts thought all of the continents were fixed. No question, the land has always been where it is now, end of story. Then people started noticing how Africa and South America seem to fit together. North America, Greenland. Europe, too. Coincidence, that’s what the experts said. Nothing more. Then they found fossils in England and North America that were identical. Same kind of rocks, too. Coincidence became stretched. Then plates were located beneath the oceans that move, and the so-called experts realized that the land could shift on those plates. Finally, in the 1960s, the experts were proven wrong. The continents were all once joined together and eventually drifted apart. What was once fantasy is now science.”

She recalled last April and their conversation at The Hague. “I thought you told me that you didn’t know beans about science.”

“I don’t. But that doesn’t mean I don’t read and pay attention.”

She smiled. “You’re quite a contradiction.”

“I’ll take that as a compliment.” Daniels pointed at the table. “Does the translation program work?”

“Seems to. And you’re right. This is a record of a lost civilization. One that’s been around a long time and apparently interacted with people all over the globe, including, according to Malone, Europeans in the ninth century.”

Daniels stood from his chair. “We think ourselves so smart. So sophisticated. We’re the first at everything. Bullshit. There’s a crapload out there we don’t know.”

“From what we’ve translated so far,” she said, “there’s apparently some technical knowledge here. Strange things. It’s going to take time to understand. And some fieldwork.”

“Malone may regret that he went down there,” Daniels muttered.

She needed to know, “Why?”

The president’s dark eyes studied her. “NR-1A used uranium for fuel, but there were several thousand gallons of oil on board for lubrication. Not a drop was ever found.” Daniels went silent. “Subs leak when they sink. Then there’s the logbook, like you learned from Rowland. Dry. Not a smudge. That means the sub was intact when Ramsey found it. And from what Rowland said, they were on the continent when Ramsey went into the water. Near the coast. Malone’s following Dietz Oberhauser’s trail, just like NR-1A did. What if the paths intersect?”

“That sub can’t still exist,” she said.

“Why not? It’s the Antarctic.” Daniels paused. “I was told half an hour ago that Malone and his entourage are now at Halvorsen Base.”

She saw that Daniels genuinely cared about what was happening, both here and to the south.

“Okay, here it is,” Daniels said. “From what I’ve learned, Ramsey employed a hired killer who goes by the name Charles C. Smith Jr.”

Davis sat still in his chair.

“I had CIA check Ramsey thoroughly and they identified this Smith character. Don’t ask me how, but they did it. He apparently uses a lot of names and Ramsey has doled out a ton of money to him. He’s probably the one who killed Sylvian, Alexander, and Scofield, and he thinks he killed Herbert Rowland—”

“And Millicent,” Davis said.

Daniels nodded.

“You found Smith?” she asked, recalling what Daniels had originally said.

“In a manner of speaking.” The president hesitated. “I came to see all this. I truly wanted to know. But I also came to tell you exactly how I think we can end this circus.”

M

ALONE STARED OUT THE HELICOPTER’S WINDOW, THE CHURN OF

the rotors pulsating in his ears. They were flying west. Brilliant sunshine streamed in through the tinted goggles that shielded his eyes. They girdled the shore, seals lounging on the ice like giant slugs, killer whales breaking the water, patrolling the ice edges for unwary prey. Rising from the coast, mountains poked upward like tombstones over an endless white cemetery, their darkness in stark contrast with the bright snow.

The aircraft veered south.

“We’re entering the restricted area,” Taperell said through the flight helmets.

The Aussie sat in the chopper’s forward right seat while a Norwegian piloted. Everyone else was huddled in an unheated rear compartment. They’d been delayed three hours by mechanical problems with the Huey. No one had stayed behind. They all seemed eager to know what was out there. Even Dorothea and Christl had calmed, though they sat as far away from each other as possible. Christl now wore a different-colored parka, her bloodied one from the plane replaced at the base.

They found the frozen horseshoe-shaped bay from the map, a fence of icebergs guarding its entrance. Blinding light reflected off the bergs’ blue ice.

The chopper crossed a mountain ridge with peaks too sheer for snow to cling to. Visibility was excellent and winds were weak, only a few wispy cirrus clouds loafing around in a bright blue sky.

Ahead he spotted something different.

Little surface snow. Instead, the ground and rock walls were colored with irregular lashings of black dolerite, gray granite, brown shale, and white limestone. Granite boulders littered the landscape in all shapes and sizes.

“A dry valley,” Taperell said. “No rain for two million years. Back then mountains rose faster than glaciers could cut their way through, so the ice was trapped on the other side. Winds sweep down off the plateau from the south and keep the ground nearly ice-and snow-free. Lots of these in the southern portion of the continent. Not as many up this way.”

“Has this one been explored?” Malone asked.

“We have fossil hunters who visit. The place is a treasure trove of them. Meteorites, too. But the visits are limited by the treaty.”

The cabin appeared, a strange apparition lying at the base of a forbidding, trackless peak.

The chopper swept over the pristine rocky terrain, then wheeled back over a landing site and descended onto gravelly sand.

Everyone clambered out, Malone last, the sleds with equipment handed to him. Taperell gave him a wink as he passed Malone his pack, signaling that he’d done as requested. Noisy rotors and blasts of freezing air assaulted him.

Two radios were included in the bundles. Malone had already arranged for a check-in six hours from now. Taperell had told them that the cabin would offer shelter, if need be. But the weather looked good for the next ten to twelve hours. Daylight wasn’t a problem since the sun wouldn’t set again until March.

Malone gave a thumbs-up and the chopper lifted away. The rhythmic thwack of rotor blades receded as it disappeared over the ridgeline.

Silence engulfed them.

Each of his breaths cracked and pinged, the air as dry as a Sahara wind. But no sense of peace mixed with the tranquility.

The cabin stood fifty yards away.

“What do we do now?” Dorothea asked.

He started off. “I say we begin with the obvious.”

EIGHTY-FIVE

M

ALONE APPROACHED THE CABIN. TAPERELL HAD BEEN RIGHT

. Seventy years old, yet its white-brown walls looked as if they’d just been delivered from the sawmill. Not a speck of rust on a single nailhead. A coil of rope hanging near the door looked new. Shutters shielded two windows. He estimated the building was maybe twenty feet square with overhanging eaves and a pitched tin roof pierced by a pipe stack chimney. A gutted seal lay against one wall, gray-black, its glassy eyes and whiskers still there, lying as if merely sleeping rather than frozen.

The door possessed no latch so he pushed it inward and raised his tinted goggles. Sides of the seal meat and sledges hung from ironbraced ceiling rafters. The same shelves from the pictures, fashioned from crates, stacked against one brown-stained wall with the same bottled and canned food, the labels still legible. Two bunks with fur sleeping bags, table, chairs, iron stove, and radio were all there. Even the magazines from the photo remained. It seemed as if the occupants had left yesterday and could return at any moment.

“This is disturbing,” Christl said.

He agreed.

Since no dust mites or insects existed to break down any organic debris, he realized the Germans’ sweat still lay frozen on the floor, along with flakes of their skin and bodily excrescences—and that Nazi presence hung heavy in the hut’s silent air.

“Grandfather was here,” Dorothea said, approaching the table and the magazines. “These are Ahnenerbe publications.”

He shook away the uncomfortable feeling, stepped to where the symbol should be carved in the floor, and saw it. The same one from the book cover, along with another crude etching.

“It’s our family crest,” Christl said.

“Seems Grandfather staked his personal claim,” Malone noted.

“What do you mean?” Werner asked.

Henn, who stood near the door, seemed to understand and grasped an iron bar by the stove. Not a speck of rust infected its surface.

“I see you know the answer, too,” Malone said.

Henn said nothing. He just forced the flat iron tip beneath the floorboards and pried them upward, revealing a black yawn in the ground and the top of a wooden ladder.

“How did you know?” Christl asked him.

“This cabin sits in an odd spot. Makes no sense, unless it’s protecting something. When I saw the photo in the book, I realized what the answer had to be.”

“We’ll need flashlights,” Werner said.

“Two are on the sled, outside. I had Taperell pack them, along with extra batteries.”

S

MITH AWOKE.

H

E WAS BACK IN HIS APARTMENT. 8:20 AM.

H

E’D

managed only three hours’ sleep, but what an excellent day already. He was ten million dollars richer, thanks to Diane McCoy, and he’d made a point to Langford Ramsey that he wasn’t someone to be taken lightly.

He switched on the television and found a

Charmed

rerun. He loved that show. Something about three sexy witches appealed to him. Naughty

and

nice. Which also seemed best how to describe Diane McCoy. She’d coolly stood by during his confrontation with Ramsey, clearly a dissatisfied woman who wanted more—and apparently knew how to get it.

He watched as Paige orbed from her house. What a trick. To dematerialize from one place, then rematerialize at another. He was somewhat like that. Slipping in, doing his job, then just as deftly slipping away.

His cell phone dinged. He recognized the number.

“And what may I do for you?” he asked Diane McCoy as he answered.

“A little more cleanup.”

“Seems the day for that.”

“The two from Asheville who almost got to Scofield. They work for me and know far too much. I wish we had time for finesse, but we don’t. They have to be eliminated.”

“And you have a way?”

“I know exactly how we’re going to do it.”

D

OROTHEA WATCHED AS

C

OTTON

M

ALONE DESCENDED INTO THE

opening beneath the cabin. What had her grandfather found? She’d been apprehensive about coming, both for the risks and unwanted personal involvements, but she was glad now that she’d made the trip. Her pack rested a few feet away, the gun inside bringing her renewed comfort. She’d overreacted on the plane. Her sister knew how to play her, keep her off balance, rub the rawest nerve in her body, and she told herself to quit taking the bait.

Werner stood with Henn, near the hut’s door. Christl sat at the radio desk.

Malone’s light played across the darkness below.

“It’s a tunnel,” he called out. “Stretches toward the mountain.”

“How far?” Christl asked.

“A long-ass way.”

Malone climbed back to the top. “I need to see something.”

He emerged and walked outside. They followed.

“I wondered about the strips of snow and ice streaking the valley. Bare ground and rock everywhere, then a few rough paths crisscrossing here and there.” He pointed toward the mountain and a seven-to eight-yard-wide path of snow that led from the hut to its base. “That’s the tunnel’s path. The air beneath is much cooler than the ground so the snow stays.”

“How do you know that?” Werner asked.

“You’ll see.”

H

ENN WAS THE FINAL ONE TO CLIMB DOWN THE LADDER.

M

ALONE

watched as they all stood in amazement. The tunnel stretched ahead in a straight path, maybe twenty feet wide, its sides black volcanic rock, its ceiling a luminous blue, casting the subterranean path in a twilight-like glow.

“This is incredible,” Christl said.

“The ice cap formed a long time ago. But it had help.” He pointed with his flashlight at what appeared to be boulders littering the floor, but they reflected back in a twinkly glow. “Some kind of quartz. They’re everywhere. Look at their shapes. My guess is they once formed the ceiling, eventually fell away, and the ice remained in a natural arch.”

Dorothea bent down and examined one of the chunks. Henn held the other flashlight and offered illumination. She joined a couple of them together: They fit like pieces in a puzzle. “You’re right. They connect.”

“Where does this lead?” Christl said.

“That’s what we’re about to find out.”

The underground air was colder than outside. He checked his wrist thermometer. Minus twenty degrees Celsius. He converted the measurement. Four below Fahrenheit. Cold, but bearable.

He was right about length—the tunnel was a couple of hundred feet long and littered with the quartz rubble. Before descending they’d lugged their gear into the hut, including the two radios. They’d brought down their backpacks and he toted spare batteries for the flashlights, but the phosphorescent glow filtering down from the ceiling easily showed the way.

The glowing ceiling ended ahead where, he estimated, they’d found the mountain and a towering archway—black and red pillars framing its sides and supporting a tympanum filled with writing similar to the books. He shone his light and noted how the square columns tapered inward toward their base, the polished surfaces shimmering with an ethereal beauty.

“Seems we’re at the right place,” Christl said.

Two doors, perhaps twelve feet tall, were barred shut. He stepped close and caressed their exterior. “Bronze.”

Bands of running spirals decorated the smooth surface. A metal bar spanned their width, held in place by thick clamps. Six heavy hinges opened toward them.

He grasped the bar and lifted it away.

Henn reached for the handle of one of the doors and swung it outward. Malone gripped the other, feeling like Dorothy entering Oz. The door’s opposite side was adorned with the same decorative spirals and bronze clamps. The portal was wide enough for all of them to enter simultaneously.

What had appeared topside as a single mountain, draped in snow, was actually three peaks crowded together, the wide cleaves between them mortared with translucent blue ice—old, cold, hard, and free of snow. The inside had once been bricked with more of the quartz blocks, like a towering stained-glass window, the joints thick and jagged. A good portion of the inner wall had fallen, but enough remained for him to see that the construction feat had been impressive. More iridescent showers of blue-tinted rays rained down through three rising joints, like massive light sticks, illuminating the cavernous space in an unearthly way.

Before them lay a city.

S

TEPHANIE HAD SPENT THE NIGHT AT

E

DWIN

D

AVIS’ APARTMENT,

a modest two-bedroom, two-bath affair in the Watergate towers. Canted walls, intersecting grids, varying ceiling heights, and plenty of curves and circles gave the rooms a cubist composition. The minimalist décor and walls the color of ripe pears created an unusual but not unpleasant feel. Davis told her the place had come furnished and he’d grown accustomed to its simplicity.

They’d returned with Daniels to Washington aboard

Marine One

and managed a few hours’ sleep. She’d showered, and Davis had arranged for her to buy a change of clothes in one of the ground-floor boutiques. Pricey, but she’d had no choice. Her clothes had seen a lot of wear. She’d left Atlanta for Charlotte thinking the trip would take one day, at best. Now she was into day three, with no end in sight. Davis, too, had cleaned up, shaved, and dressed in navy corduroy trousers and a pale yellow oxford-cloth shirt. His face was still bruised from the fight but looked better.