The Closing of the Western Mind: The Rise of Faith and the Fall of Reason (69 page)

Read The Closing of the Western Mind: The Rise of Faith and the Fall of Reason Online

Authors: Charles Freeman

Tags: #History

Morris, Jan.

Trieste and the Meaning of Nowhere.

London, 2001.

Moores, J. D.

Wrestling with Rationality in Paul.

Cambridge, 1995.

Mortley, Raoul.

From Word to Silence.

Vol. 1:

The Rise and Fall of

Logos. Vol. 2:

The Way of Negation, Christian and Greek.

Bonn, 1986.

Murphy-O’Connor, Jerome. The Holy Land: An Oxford Archaeological Guide. 4th ed. Oxford, 1998.

———.

Paul: A Critical Life.

Oxford, 1996.

Murray, Oswyn.

Early Greece.

2nd ed. London, 1993.

Murray, Oswyn, and Simon Price, eds.

The Greek City from Homer to Alexander.

Oxford 1990.

Newbould, R. F. “Personality Structure and Response to Adversity in Early Christian Hagiography.”

Numen

31 (1984).

New Catholic Encyclopedia. Washington, D.C., 1967.

Nussbaum, Martha.

The Fragility of Goodness.

Cambridge, 1986.

———. “Platonic Love and Colorado Love: The Relevance of Ancient Greek Norms to Modern Sexual Controversies.” In R. B. Louden and P. Schollmeier, eds., The Greeks and Us: Essays in Honor of Arthur W. H. Adkins. Chicago and London, 1999.

———.

The Therapy of Desire: Theory and Practice in Hellenistic Ethics.

Princeton, 1994.

Ober, Josiah.

Political Dissent in Democratic Athens: Intellectual Critics of Popular

Rule.

Princeton and Chichester, Eng., 1998.

Osborne, Robin. Greece in the Making, 1200–479 B.C. London, 1996.

O’Shea, Stephen. The Perfect Heresy: Life and Death of the Cathars. London, 2000. Pagels, Elaine.

The Gnostic Gospels.

London 1980.

Parker, Robert.

Athenian Religion: A History.

Oxford, 1996.

Partridge, Loren.

The Renaissance in Rome.

London, 1996.

Pearson, B., ed.

The Future of Early Christianity: Essays in Honor of Helmut

Koester.

Minneapolis, 1991.

Pelikan, Jaroslav.

Christianity and Classical Culture.

New Haven and London, 1993.

———.

The Christian Tradition.

Vol. 1:

The Emergence of the Catholic Tradition

(

100–600

). Chicago and London, 1971.

Pickman, E. M.

The Mind of Latin Christendom.

New York, 1937.

Pohlsander, H.

Constantine the Emperor.

London, 1997.

Popkin, Richard, ed.

The Pimlico History of Western Philosophy.

New York, 1998; London, 1999.

Popper, Karl.

The Open Society and Its Enemies.

1945; republ. London, 1995.

Porter, J. R.

Jesus Christ: The Jesus of History, the Christ of Faith.

London, 1999.

Porter, Roy.

The Greatest Benefit to Mankind: A Medical History of Humanity from

Antiquity to the Present.

London, 1997.

Powell, J. G. F., ed.

Cicero the Philosopher.

Oxford, 1995.

Powell, Mark Allen.

The Jesus Debate.

Oxford, 1999.

Price, Simon.

Religions of the Ancient Greeks.

Cambridge, 1999.

———.

Rituals and Power: The Roman Imperial Cult in Asia Minor.

Cambridge, 1984.

Ranke-Heinemann, Uta.

Eunuchs for the Kingdom of Heaven: Women, Sexuality

and the Catholic Church. Trans. P. Heinegg. New York, 1990.

Rawson, Elizabeth.

Cicero: A Portrait.

London, 1995.

Reinhold, M., and N. Lewis.

Roman Civilization, Sourcebook II: The Empire.

New York, 1995.

Richards, Hubert.

St Paul and His Epistles: A New Introduction.

London, 1979. Rihill, T. E.

Greek Science.

Oxford, 1999.

Rist, John.

Augustine: Ancient Thought Baptised.

Cambridge, 1994.

———. “Plotinus and Christian Philosophy.” In Lloyd P. Gerson, ed., The Cambridge

Companion to Plotinus.

Cambridge, 1996.

Rives, J.

Religion and Authority in Roman Carthage from Augustus to Constantine.

Oxford, 1995.

Robb, Kevin, ed.

Language and Thought in Early Greek Philosophy.

La Salle, Ill., 1983.

Rogerson, John, ed.

The Oxford Illustrated History of the Bible.

Oxford, 2001.

Rorem, Paul. “The Uplifting Spirituality of Pseudo-Dionysius.” In Bernard McGinn and John Meyendorff, eds.,

Christian Spirituality: Origins to the Twelfth Century.

London, 1986.

Rousseau, Philip.

Ascetics, Authority and the Church in the Age of Jerome and

Cassian.

Oxford, 1978.

Ruether, Rosemary.

Faith and Fratricide: The Theological Roots of Anti-Semitism.

New York, 1974.

———.

Gregory of Nazianzus: Rhetor and Philosopher.

Oxford, 1969.

Runciman, W. G. “Doomed to Extinction: The Polis as an Evolutionary Dead-End.” In Oswyn Murray and Simon Price, eds.,

The Greek City from Homer to

Alexander.

Oxford, 1990.

Sanders, E. P. The Historical Figure of Jesus. Harmondsworth, 1993.

———.

Paul.

Oxford, 1991.

Segal, Alan. “Universalism in Judaism and Christianity.” In Troels Engbury-Pedersen, ed.,

Paul in His Hellenistic Context.

Edinburgh, 1994.

Shipley, Graham. The Greek World After Alexander, 323–30 B.C. London, 2000.

Shotter, David.

The Fall of the Roman Republic.

London and New York, 1994.

Sim, David C. The Gospel of Matthew and Christian Judaism. Edinburgh, 1998.

Simmons, M. B. “Julian the Apostate.” In P. Esler, ed., The Early Christian World, vol. 2. New York and London, 2000.

Simon, Marcus.

Verus Israel.

Oxford, 1986.

Simonetti, M.

Profilo storico dell’esegesi patristica.

Rome, 1980.

Singer, Peter.

Animal Liberation.

2nd ed. London, 1990.

Siorvanes, Lucas.

Proclus: Neo-Platonic Philosophy and Science.

Edinburgh, 1996. Smith, R. R. R.

Hellenistic Sculpture.

London, 1991.

Smith, Rowland.

Julian’s Gods: Religion and Philosophy in the Thought and Action

of Julian the Apostate.

London and New York, 1995.

Sorabji, Richard.

Emotion and Peace of Mind: From Stoic Agitation to Christian

Temptation.

Oxford, 2000.

———. “Rationality.” In Michael Frede and Gisela Striker, eds.,

Rationality in

Greek Thought.

Oxford, 1996.

Stark, Rodney.

The Rise of Christianity.

Princeton, 1996.

Stead, Christopher.

Philosophy in Christian Antiquity.

Cambridge, 1994.

———. “Rhetorical Method in Athanasius.”

Vigiliae Christianae

30 (1976): 121–37.

Stegemann, E. W., and W. Stegemann. The Jesus Movement: A Social History of Its

First Century.

Edinburgh, 1999.

Steiner, Deborah.

The Tyrant’s Writ.

Princeton, 1993.

Straw, Carole.

Gregory the Great: Perfection in Imperfection.

Berkeley and London, 1988.

Stroumsa, Guy.

Barbarian Philosophy: The Religious Revolution of Early

Christianity.

Tubingen, 1999.

Swain, S. Hellenism and Empire: Language, Classicism and Power in the Greek

World, A.D. 50–250.

Oxford, 1996.

Tallis, Raymond.

Enemies of Hope: A Critique of Contemporary Pessimism.

London, 1997.

Tarn, William.

Alexander.

Cambridge, 1948.

Tarnas, Richard.

The Passion of the Western Mind.

London, 1996.

Tarrant, Harold. “Middle Platonism.” In Richard Popkin, ed.,

The Pimlico History

of Western Philosophy.

New York, 1998; London, 1999.

Taylor, Miriam.

Anti-Judaism and Early Christian Identity.

Leiden and New York, 1995.

Thomas, Keith.

Man and the Natural World: Changing Attitudes in England,

1500–1800.

London, 1983.

Thomas, Rosalind.

Herodotus in Context: Ethnography, Science and the Art of

Persuasion.

Cambridge, 2000.

Thompson, E. A.

The Visigoths in the Time of Ulfila.

Oxford, 1966.

Tilley, Maureen. “Dilatory Donatists or Procrastinating Catholics: The Trial at the Conference of Carthage.” In Everett Ferguson, ed.,

Doctrinal Diversity: Varieties

of Early Christianity.

New York and London, 1999.

Trout, Dennis.

Paulinus of Nola: Life, Letters and Poems.

Berkeley and London, 1999.

Vaggione, Richard.

Eunomius of Cyzicus and the Nicene Revolution.

Oxford, 2000. Vermes, G.

The Changing Faces of Jesus.

London, 2000.

Wallace, R., and W. Williams. The Three Worlds of Paul of Tarsus. London, 1998. Wardy, Robert.

The Birth of Rhetoric.

London, 1996.

———. “Rhetoric.” In J. Brunschwig and G. E. R. Lloyd, eds.,

Greek Thought: A

Guide to Classical Knowledge.

Cambridge, Mass., and London, 2000.

Ware, Kallistos. “The Soul in Greek Christianity.” In C. Crabbe and M. James, eds.,

From Soul to Self.

London, and New York, 1999.

———. “The Way of the Ascetics, Negative or Affirmative?” In V. Wimbush and R. Valantasis, eds.,

Asceticism.

New York and Oxford, 1995.

Warner, Marina.

Alone of All Her Sex.

London, 1985.

Weitzmann, K., ed. Age of Spirituality: A Symposium. New York, 1980.

West, Martin. “Early Greek Philosophy.” In John Boardman, Jasper Griffin and Oswyn Murray, eds.,

The Oxford History of the Classical World.

Oxford, 1986.

Wiles, Maurice.

Archetypal Heresy: Arianism Through the Centuries.

Oxford, 1996.

Wilken, R. L. John Chrysostom and the Jews: Rhetoric and Reality in the Late

Fourth Century.

Berkeley and London, 1983.

Williams, Bernard. “Philosophy.” In M. J. Finley, ed.,

The Legacy of Greece: A New

Appraisal.

Oxford, 1984.

Williams, Daniel.

Ambrose of Milan and the End of Nicene–Arian Conflicts.

Oxford, 1995.

Williams, Rowan. “Arianism.” In E. Ferguson, ed.,

Encyclopaedia of Early Christianity.

Chicago and London, 1990.

———, ed.

The Making of Orthodoxy: Essays in Honour of Henry Chadwick.

Cambridge, 1989.

Williams, Stephen.

Diocletian and the Roman Recovery.

London, 1985.

Wills, Gary.

Saint Augustine.

London and New York, 1999.

Wimbush, V., and R. Valantasis, eds. Asceticism. New York and Oxford, 1995.

Wisch, B., ed.

Confraternities and the Visual Arts in Renaissance Italy: Ritual,

Spectacle, Image.

Cambridge, 2000.

Witt, R.

Isis in the Greco-Roman World.

London, 1971.

Wolterstorff, Nicholas. “Faith.” In

Routledge Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

London and New York, 2000.

Worthington, Ian, ed.

Persuasion: Greek Rhetoric in Action.

London and New York, 1994.

Wood, D., ed.

The Church and the Arts.

Oxford, 1992.

Young, Frances. “A Cloud of Witnesses.” In John Hick, ed.,

The Myth of God

Incarnate,

2nd ed. London, 1993.

———.

From Nicaea to Chalcedon.

London, 1993.

Zanker, Paul.

The Power of Images in the Age of Augustus.

Ann Arbor, 1988.

1, 2. Two details from “The Triumph of Faith” by Filippino Lippi, painted in the 1480S for the Dominican church of Santa Maria sopra Minerva in Rome. The great Dominican theologian Thomas Aquinas upholds the true faith, while below him the works of heretics lie discarded. The figures below Aquinas include the fourth-century combatants in the dispute, among them Arius and Sabellius, as well as contemporaries of the donor of the fresco, Cardinal Oliviero Carafa (1430–1511), the cardinal protector of the Dominicans.

Note Constantine’s church of St. John Lateran in the view to the left of Aquinas (top) with the famous equestrian statue of Marcus Aurelius, then believed to be of Constantine, which is now on the Capitoline Hill. For further discussion of the fresco, see chapter 1. (Credit: Scala)

3, 4. “There is one race of men, one race of gods, both have breath of life from a single mother . . . so we have some likeness, in great intelligence and strength to the immortals.” The poet Pindar, writing in the fifth century B.C., notes the contrasts and similarities between men and the gods in the Greek world. The Riace warrior (above), which forms part of an Athenian victory monument at Delphi (470s B.C.), represents man at his most heroic, almost a god in his own right, as the similarity to a portrayal of Zeus in a bronze of the same date (right) makes clear. This was the human world at its most confident, although the Greeks always warned of the impropriety of a mortal attempting to behave as if he were a god. (Credit: Ancient Art and Architecture Collection)

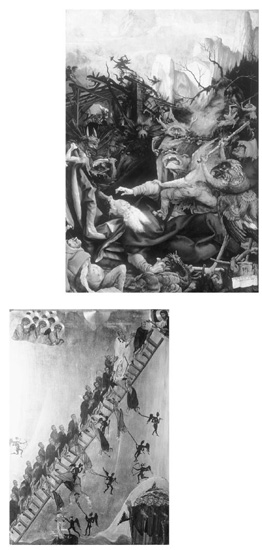

5, 6. By the fourth century A.D., such confidence has faded and human beings have become overwhelmed by forces over which they have little control. The gulf between God and man is now immense. On earth, the ascetic Anthony, here shown on the Isenheim Altar (above), painted for a monastery dedicated to St. Anthony in Alsace by Matthias Grünewald (1515), fights off a host of demons which threaten to overcome him (credit: Bridgeman Art Library). In the afterlife (left), devils drag unlucky souls down into hell from the ladder on which they are making the arduous ascent towards heaven (a twelfth-century icon from St. Catherine’s Monastery in Sinai; credit: Ancient Art and Architecture Collection). It was perhaps inevitable in such a climate that creative thinking about the natural world would be stifled.

7. Marcus Aurelius (emperor A.D. 161–80) displays himself as one among his fellow humans. Here, in a contemporary panel (C. 176–80 A.D.) in Rome, he grants clemency to two kneeling barbarians (credit: Corbis). In his

Meditations

, much influenced by Stoicism, Marcus Aurelius stresses his optimism about the natural order of things. “Everything bears fruit: man, God, the whole universe, each in its proper season. Reason, too, yields fruit, both for itself and for the world; since from it comes a harvest of other good things, themselves all bearing the stamp of reason.”

8, 9, 10. By the fourth century the emperor has become quasi-divine, as the monumental idealized head of Constantine (above left), from his basilica in Rome, suggests (credit: Scala). Recent studies of Constantine doubt that he was ever fully converted to Christianity, but aimed instead to bring Christianity, alongside paganism, into the service of the state. His Arch in Rome (315) (top) shows no Christian influence, but one can see in the third line of the inscription the words INSTINCTU DIVINITAS, “by divine inspiration,” a use of terminology acceptable to both Christian and pagan (credit: Scala). In a coin of about 330 (above right), Constantine stands between two of his sons (credit: Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna). He receives a circlet directly from God, a symbol of divine approval of his rule, while Constantius is crowned by Virtus (virtue) and Constantine II by Victoria (victory). In Christian terms, Constantine sees himself as the “thirteenth apostle” and is buried as such.

11, 12, 13. By 390 Christ, here “in majesty” in the church of Santa Pudenziana in Rome (top), has been transformed from an outcast of the empire to one who is represented by its most traditional imperial images, fully frontal on a throne (credit: Scala). The setting echoes the portrayal of Constantine distributing largesse on his Arch (315) (above; credit: Alinari) and of the emperor Theodosius I on a silver commemorative dish of 388 (right; credit: Ancient Art and Architecture Collection). Note Christ’s adoption of a halo, hitherto a symbol of monarchy (while his beard echoes representations of Jupiter). On Christ’s left, Paul is introduced as an apostle, an indication of his growing status in the empire of the late fourth century.

14. According to the Gospels, Jesus was executed by Roman soldiers and offered no resistance to them. In imperial Christianity, by contrast, he himself has become a Roman soldier, “the leader of the legions,” as Ambrose of Milan put it. With no supporting evidence for this role from the Gospels, the Old Testament Psalm 91, which portrays a protective God trampling on lion and adder, is drawn on to provide the imagery. (A mosaic from Ravenna, c. 500; credit: Scala)

15. Constantine’s use of a military victory as the platform from which to announce his toleration of Christianity was a radical departure which defined the relationship between Christianity and war for centuries to come. The Sala di Constantino was commissioned from Raphael by the Medici pope Leo X (pope 1513–21). The early popes are shown alongside Constantine’s vision. Leo associated himself with the victory by adding the

palle

(balls) from the Medici coat of arms to Constantine’s tent; lions, a reference to Leo’s name, are also found on the tent, with another depicted on a standard. (Credit: Scala)